Return to Normandy

My experience as a Spitfire fighter pilot in the Second World War, in the cause of restoring freedom and justice, has been a compelling influence throughout my life.

This, journal is an opportunity to organize my thoughts on a profoundly humbling series of events both then and now. It is done in the hope it will evoke a better appreciation of the enormous contribution Canada made in helping secure the allied victory.

D-Day was the largest sea borne invasion in history, and Supreme Allied Commander, General Dwight David Eisenhower carried the weight of his responsibility with him on that day in the form of a note he planned to release in the event it did not succeed.

"Our landings have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have ordered a withdrawal of the invasion force," it read. "Our troops, air force and navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt, it is mine alone."

Arrival in Ottawa

Tuesday – 1 June 2004

My journey to Normandy began in Burlington, Ontario. My flight from nearby Hamilton to Ottawa was delayed by about four hours. Upon arriving in Ottawa, I met with my old friend and 412 Squadron comrade Barry Needham, who was coming from Wynyard, Saskatchewan.

We ventured up the street to a piano bar. It was about to close but when the owner learned we were Veterans going to Normandy for the 60th anniversary celebrations of D-Day. He kept his bar open for an extended period and joined us.

Arrival in France

Thursday – 3 June 2004

Four buses were needed to transport the 60 Veterans, 30 students and a dozen or so Veterans Affairs personnel. Sixteen of the Veterans were in wheelchairs, including Smokey Smith, Canada's lone surviving recipient of the Victoria Cross.

We touched down at about 8:30 am local time at Evreux Air Force Base in Normandy and French officials greeted us one after the other as we stepped off the plane.

The first event

Friday – 4 June 2004

The first scheduled event of the week was a parade at Saint Aubin-sur-Mer, a small community on the eastern end of Juno Beach. The assembly area for all those participating was a mile or so outside the town. There were a large number of Second World War transport vehicles parked along the road. We were going to ride into Saint Aubin in style, aboard these restored jeeps and trucks.

I climbed aboard one jeep with my two buddies, F/L Charley Fox from London, Ontario, and F/L Barry Needham.

As we reached the outskirts of St. Aubin, the joyous, enthusiastic, wildly cheering citizens were unbelievably boisterous and friendly. Almost every home we passed was flying a Canadian flag, and every student in St. Aubin was waving a red Maple Leaf to let us Canadians know how much we were appreciated.

The Governor General of Canada, Adrienne Clarkson arrived and very eloquently expressed the appreciation of all Veterans to the welcome given by the townspeople.

The mayor insisted on meeting every Veteran in attendance. And I could hardly wait for the opportunity to shake hands with as many students as possible and to give each of them a Canadian flag pin to remember us by.

Paying our respects to the fallen

Saturday – 5 June 2004

Our first stop on this day was for a commemorative ceremony at Courseulles-sur-Mer, one of the three landing sites for the Canadians on D-Day.

This town is the site of the Juno Beach Centre, a distinctive museum to preserve and share the story of the Canadian involvement in the Second World War.

Beny-sur-Mer

A short distance away is the town of Beny-sur-Mer, a place of special significance for me. That is where 126 Wing, comprising three Canadian Spitfire Squadrons, were stationed starting on 19 June 1944, just two weeks after D-Day. Our airstrip, code-named B-4, would be our base for 51 days while the battle for Caen raged on, just four miles away.

Today, we were taking part in a commemorative ceremony at the Canadian War Cemetery at Beny-sur-Mer. Few if any of the Veterans were aware of the special meaning that place held for two pilots, including myself.

In June 1944, there were 14 air bases in Normandy comprising the total offensive capacity of the 2nd Tactical Air Force that included Spitfires, Mustangs and Typhoons (a fighter-bomber).

We flew across the English Channel three times daily from dawn until dusk to provide cover over Juno Beach for the Canadian 3rd Division and the British 2nd Army. Operations ended at dusk, as Spitfires were day fighters only, and not suitable for night fighting.

In all there were approximately one thousand officers and men at the airfield – larger by the way, than many communities in Normandy. Our strip was just wire mesh, 60 yards in width and 1,300 yards in length lying on the ground. From that areathree squadrons of Spitfires (12 planes each_ would take off and land several times a day.

An important day

Courseulles-sur-Mer

Upon getting a 5:30 am wake up call, I couldn't help but recall that by this time, sixty years earlier, I was in a Spitfire flying over Juno Beach.

There were two major ceremonies scheduled for today. The first was a Commonwealth ceremony at Courseulles and the second was the international ceremony at Arromanches.

At Courselles I climbed the huge outside bleachers to await the arrival of the dignitaries which included Queen Elizabeth II, Prince Phillip, Governor General Adrienne Clarkson, the Prime Minister of Canada Paul Martin, among others.

And then, I would find myself seated with them all, immediately behind Queen Elizabeth. Upon introduction by the Minister of Veterans Affairs, John McCallum, I had the honour of reading the Act of Remembrance. My wife, back home in Burlington, watching quite by accident, was flabbergasted, as was I, but everything went very smoothly.

At the conclusion of the ceremony, there was a fly past by a Lancaster bomber and two Spitfires, a reminder of the vital part played by the air force throughout the war and particularly the liberation of France.

Despite the important advantages the Allies possessed, it is certain the Normandy invasion would not have succeeded without our air supremacy.

After the service, virtually every Veteran spent some time alone on the beachhead reflecting on what a different place it was sixty years ago.

Arromanches

We then departed for the international ceremony at Arromanches – which included the heads of state from almost every Allied country.

We listened to the inspiring message from the President of France, Jacques Chirac, and viewed a two-hour presentation including a march past by Veterans, a fly past and a naval display in the nearby Channel.

A day in Caen and nearby sites

Caen

It was fitting that a complete day be spent in the Caen area, as the capture of that city was essential to the allied victory. For the Nazis, Caen was their key communications and supply route for all of Normandy.

The battle for Caen lasted two agonizing months. On 6 June 1944, there was a heavy bombing raid and fire would rage for 11 days. The central area was completely burned out, and the residents had to seek refuge in St. Etienne Church. During the battle more than 1,500 refugees were camped out there. Another 4,000 people stayed in the nearby hospice at Bon-Sauver.

During their attack the Allies were alerted of these two groups of civilians by the Prefect and by the Resistance, and these buildings, and the people,were spared. The quarries at Fleury, one mile south of Caen, provided the largest refuge. Despite the cold and damp, whole families would live here until the end of July.

The Caen Memorial

The Caen Memorial is a museum for peace. It is primarily a place for commemoration and of permanent mediation on the connection between human rights and the maintenance of peace.

The façade of the building, facing Dwight Eisenhower Esplanade, is marked by a fissure that evokes the destruction of the city and the breakthrough of the Allies in the liberation of France and Europe from the Nazis. It stands on the site of the bunker of General Richter, the leader of the German troops who fought against the Canadians on D-Day.

The time spent at this memorial site was unfortunately limited, as we had to get to Place De L'Ancienne Boucherie and the infamous Abbaye d'Ardenne, where 20 Canadian prisoners of war were murdered under the command of SS Colonel Kurt Meyer.

A pilgrimage to say goodbye to Bob Davidson

Tuesday – 8 June 2004

Today I took a detour from the official delegation to pay my respects to a lost comrade, Bob Davidson.

On 27 June 1944, 126 Wing was at Beny-sur-Mer,

and I learned that Pilot Officer Bob Davidson, a friend from my hometown had been posted with us. I hustled over to see him. We had a great time discussing things back home and I left him with plans to get to together again as soon as possible.

It was not to be…

The following day, Bob Davidson was shot down and killed in the Argentan area of Normandy, not far from our home base.Despite the fact that losses like this were a frequent experience, it came as a great shock.

…then ten years ago in 1994

In our Canadian Fighter Pilots bulletin there was a request from someone searching for anyone who knew Bob Davidson, and to contact Norbert Hureau in Argentan. Norbert had a ring belonging to Bob and he wanted to see if he could get it returned to the Davidson family.

I reached out to Mr. Hureau who turned out to have been a part of the “French resistance” and had been the one who recovered Bob’s body and had arranged for a proper burial.

Through a translator, we agreed to meet after the delegation’s visit to the Bretteville-sur-Laize Canadian War Cemetery in Cintheaux. At long last I would be able to pay my respects at the gravesite of my long lost friend from 401 Squadron.

Hureau drove me to the exact location where Bob had been shot down, in a hamlet named Courteres, and then we went to his burial site in the cemetery of a small church in Lignou. It was a very meaningful experience for me.

After this, he took me back to a school where I met with a group of students who had been waiting over two hours to meet the friend of the Canadian pilot buried in their cemetery.

What a day! Despite my late arrival back in Deauville at 8 pm to rejoin the group. it was very special for me to have the opportunity to salute my colleague and friend Bob Davidson and to say a formal goodbye to him.

Sharing some stories

Wednesday – 9 June 2004

We departed for a return visit to Beny-sur-Mer Cemetery before 8 am. The visit provided the opportunity for a more personal moment at the gravesite of our fallen comrades. The inscriptions on the headstone at each grave evidenced the burden felt by each family in Canada.

After dinner in Deauville, I had the pleasure of meeting the students from across Canada who were selected to make the Normandy pilgrimage.

I had not prepared any particular remarks, so I told them about the Falcon Squadron. And I told them about John Gillespie Magee, an American from New York, who came to Canada to volunteer in the Air Force and who later wrote the sonnet "High Flight," which now hangs in the officers' mess of every Canadian air establishment.

I spoke about the achievement and valour of George Beurling, the top Canadian pilot in the Second World War. He did his first tour of operations in Malta and later flew with 412 Squadron. Beurling had a great influence on my life and career. I spoke of his putting me in an ambulance at Biggin Hill airfield, after my fateful return from escorting American bombers, and then my disappointment finding him gone when I returned to service after the hospital. and the immense honour it was to be assigned VZ-B, George's aircraft.

By any measure, having the young people learn of Magee and Beurling, and receiving such a wonderful response to my presentation, was one of the highlights of this trip to Normandy.

The last day

Thursday – 10 June 2004

The farewell dinner at our hotel was magnificent. The Governor General gave a heartwarming speech, extolling the virtues of the Canadian service people on hand, and emphasizing that we had all been volunteers, just determined to make a difference.

After dinner, the chap next to me left to pack his suitcase. and then I sensed that someone had taken his chair. Lo and behold, it was Governor General Adrienne Clarkson! Her first words were, "Well, tell me about 412 Squadron."

I responded, "Your Excellency, we were a group with very remarkable pilots and one in particular had the distinction of being the most successful of all Canadian pilots in the Second World War. Would you know who that might be?"

She pondered a minute before responding, "Would that be George Beurling?"

Those within earshot were shocked, but she said, "You see, I grew up in Montreal, and that's where George lived."

Some final thoughts

This completes the story of my return to Normandy. It was an experience I would never have imagined in my wildest dreams, and it was fascinating in so many ways.

Thinking back on my memories from 1944, I could never envisage that Normandy could be the beautiful and exciting area it is today.

The poem, “High Flight”

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of earth

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings;

Sunward I've climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth

Of sun-split clouds - and done a hundred things

You have not dreamed of - wheeled and soared and swung

High in the sunlit silence. Hov'ring there

I've chased the shouting wind along, and flung

My eager craft through footless halls of air.

Up, up the long delirious, burning blue,

I've topped the windswept heights with easy grace

Where never lark, or even eagle flew -

And, while with silent lifting mind I've trod

The high untresspassed sanctity of space,

Put out my hand and touched the face of God.

Mistaken identity

Flight Lieutenant George Beurling, DSO, DFC, DFM and Bar was the top Canadian fighter pilot in the Second World War, with 32.5 enemy aircraft victories to his credit.

Dubbed “Buzz” Beurling by the press, he achieved lasting fame for his exploits over Malta in the Mediterranean sector. He later flew at Biggin Hill with 412, the Falcon Squadron.

Beurling, like many fighter pilots, recorded his victories on the fuselage of his plane with a swastika representing each of his kills. His Spitfire had the call letters VZ-B. In Beurling's case, the number of swastikas painted on the fuselage of his aircraft quickly became a focal point on the ground or in the air.

On 21 February 1944, we gathered for a regular briefing to get particulars on a bombing raid in northern Holland, which turned out to be an escort mission to provide air cover for U.S. Marauders.

Beurling, to no one's surprise, regarded escort missions as non-productive from the standpoint of challenging enemy aircraft. So he proceeded to remove his name from the board and replaced it with mine, which was his prerogative as a Flight Commander.

For sure, it was a distinction to fly George's aircraft, but I did not anticipate what would occur as we landed at Manston Airfield on the east coast of England to load up on fuel before crossing the Channel.

A member of the ground crew guided me into position and viewed the 32 swastikas on the aircraft. He then immediately called everyone within earshot, while waving frantically to hurry over and shake the hand of the pilot flying the kite with 32 swastikas. He thought Manston airfield had received a distinctive visitor that day.

More than a little embarrassed by the misdirected attention, I could hardly wait until my return to Biggin Hill and a chance to tell George the excitement he had missed by erasing his name from the board.

My crash landing

Only two weeks after my case of mistaken identity, the Falcon Squadron was again called upon to escort U.S. Marauders, this time to bomb a German airfield in France. It was a two-and-a-half-hour journey, again with a stop for refuelling at Manston Airfield.

Spitfires land with a particular nose-up approach, making visuals of the runway difficult. And so on our return to Biggin Hill, I barely had an instant of warning that another pilot on the squadron had landed, then turned his aircraft 180 degrees; climbed out and had left it right there on the runway.

Immediately on collapse of the undercarriage, my aircraft was consumed in fire. As quickly as possible I was able to climb out of the aircraft and stumble to the airstrip. My first reaction, after seeing several members of the groundcrew running to my aid, was that they would not reach me in time.

I was fortunate, as our doc was able to remove as much of the burned clothing as possible and prepared me for immediate transport to East Grinstead. It was George Beurling who assisted me into the ambulance. I never saw him again.

On my return to 412 Squadron, he had already left for Canada. But I remember his last words like it happened yesterday: "Don't worry Lloyd, you'll be okay."

It took four operations but George was right.

Two unsuccessful ones at Queen Victoria Hospital in the United Kingdom, after which I returned to my Squadron at Tangmere. I then had two more operations on my return to Canada, ironically at the same place where I had earned my wings two years earlier, at #14 Service Flying Training School at Aylmer, Ontario, which was converted into a Veterans hospital after the war.

In all, my complete tour of operations serving in 412 Squadron involved more than 200 sorties.

First landing at B-4 – The “beer run”

On 13 June 1944 (D-Day plus seven), 412 Squadron, along with the others comprising 126 Wing, gathered for a briefing by Wing Commander Keith Hodson at our Tangmere base.

We would get details of our now-regular beach patrol activities, only this one had a slight variation. Hodson singled me out to arrange delivery of a sizable shipment of beer to our future airstrip being completed at Beny-sur-Mer.

The instructions went something like this:

"Get a couple other pilots and arrange with the officers’ mess to steam out the jet tanks and load them up with beer. When we get over the beachhead, drop out of formation and land there. We're told the Nazis are fouling the drinking water, so it will be appreciated. There'll be no trouble finding the strip, the Battleship Rodney is firing salvoes on Caen and it's immediately below. We'll be flying over at 13,000 so the beer will be cold enough when you arrive."

I remember getting Murray Haver from Hamilton and a third pilot (whose name escapes me) to carry out the “mission.”

By the time I got down to 5,000 feet, the welcoming from the Rodney was hardly inviting. But sure enough, there was the air strip.

Wheels down and in we went, three Spits with 90gallon jet tanks fully loaded with cold beer.

As I rolled to the end of the mesh runway, it was hard to figure things out. There was absolutely no one in sight. What do we do now, I wondered? We can't just sit here and wait for someone to show up. What's going on?

Finally I saw someone peering out at us from behind a tree and I waved frantically to get him out to my aircraft. Sure enough out of bounds, this army type, and he climbs onto the wing with an unexpected welcome, "What the hell are you doing here?"

He got a short, terse, version of the story from me.

"Look," he said "can you see that church steeple at the far end of the strip? Well it's loaded with German snipers and we've been here all day trying to clear them out. So you better drop your tanks and bugger off before it's too late."

Within moments we were out of there but that was the welcoming for the first Spitfires to land at our B4 airstrip in Normandy.

The unbelievable sequel to this story took place in the early 1950s at Ford Motor Company in Windsor, where I was working at the time.

A chap arrived to discuss some business and inquired if I had served in the Air Force. "Yes, indeed," I responded.

"Did you by chance land at Beny-sur-Mer in Normandy with two other Spitfires loaded with jet tanks full of beer?" he asked.

"Yes, for sure I did. But how on earth would you know that?”

“Well I’ll tell you,” he said, “I was the guy who climbed on your wing and told you to bugger off.”

No surprise that we spent the rest of the afternoon reminiscing.

What is a day fighter?

Bomber air crews and night fighters seldom viewed the English Channel or the area they attacked.

While for those of us in day fighters, our home airfield was based where we were operating. We knew the beaches of Normandy because we flew over them every day, more often than not several times daily.

Pilots of single engine day fighters were totally responsible for both landing and take-off. It was essential to be a competent navigator as you would often experience radio breakdown, removing any other assistance to find your airfield.

Map reading was essential for reaching your target and to avoid anti-aircraft locations. This anti-aircraft fire would cost us many Spitfires and the pilots. Combat flying required a dexterity gained largely from experience in manoeuvring the aircraft successfully and being proficient in air firing, which we practiced as much as possible. Also, being very lucky helped, too!

As day fighters, we also contributed useful data for military intelligence. After every flight we were obliged to report to our intelligence officer on anything of importance that we saw.

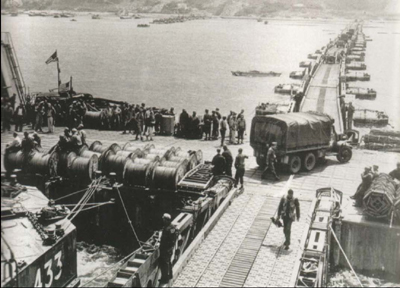

What is a Mulberry harbour?

Perhaps the one constant in war is the inherent difficulty maintaining adequate supply routes for the troops. As Canadians moved through the low countries, it was vital that a large port be liberated so it could allow supplies to flow. Canadians played a key role in the liberation of that key port, Antwerp, Belgium.

Before Antwerp was liberated, the Allies had to build two artificial harbours, known as Mulberry's, one in the American sector and the other for the British and Canadians at Arromanches.

The Mulberry in the American sector was destroyed by storms shortly after D-Day, but the one at Arromanches would supply the Allies for 10 months until Antwerp was freed.

Two and a half million men, a half-million vehicles and untold tons of supplies landed in Normandy through this artificial harbour at Arromanches.

Lloyd passed away in 2012. With courage, integrity and loyalty, he left his mark. Discover more stories.