When we Came Back, the Guards Were all Gone

Heroes Remember

When we Came Back, the Guards Were all Gone

Transcript

Description

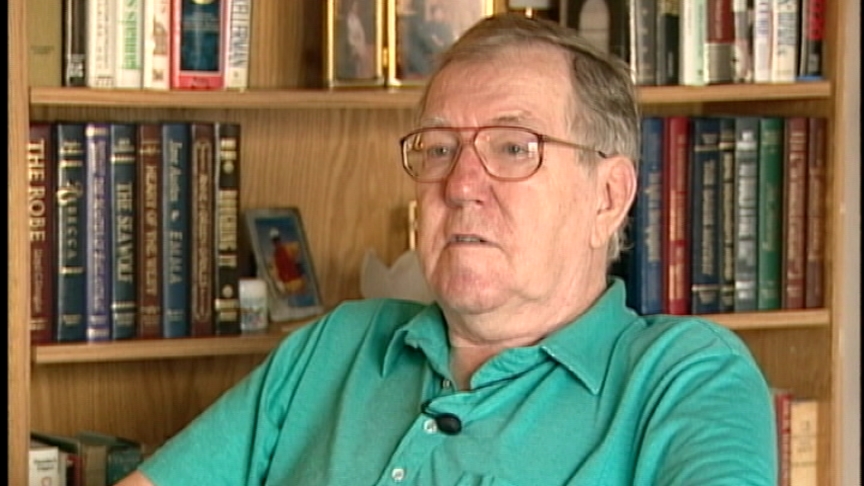

Mr. Jessop describes events in Omine camp that indicated the war was ending.

James Robert Jessop

James Robert Jessop was born in Edmunston, New Brunswick, in 1921. He and his twin brother were the eldest sons among nine children. His father worked full-time as a mechanic at the local pulp mill. Mr. Jessop recalls having had good teachers in school, where he also played hockey and rugby. He eventually worked at Fraser’s Mill for twenty-four cents an hour, but enlisted in 1940 for the prospect of better wages. He applied for and was accepted into the Royal Canadian Air Force, but switched to the Royal Rifles to be with his brother. Before leaving for Hong Kong, Mr. Jessop trained and served in several places in Newfoundland. Mr. Jessop’s experiences in the Hong Kong campaign were typical; forced to surrender and work as slave labor in both Sham Shui Po and Omine, malnourished, ravaged by disease and subjected to abuse at the hands of his captors. He also witnessed first hand the devastation of Nagasaki. Mr. Jessop’s service ends with a touching family reunion and a heartfelt sense of loss for his fallen friends.

Meta Data

- Medium:

- Video

- Owner:

- Veterans Affairs Canada

- Duration:

- 3:28

- Person Interviewed:

- James Robert Jessop

- War, Conflict or Mission:

- Second World War

- Location/Theatre:

- Japan

- Battle/Campaign:

- Hong Kong

- Branch:

- Army

- Units/Ship:

- Royal Rifles of Canada

- Rank:

- Lance-Corporal

Related Videos

- Date modified: