3.1 Alignment with Government Priorities

The Career Transition Services Program objective is aligned with Government priorities.

The objective of the Career Transition Services Program is to provide funds to eligible CAF Veterans (Regular and Reserve Force) and survivors to secure career transition services to help them obtain civilian employment. Essentially, the Program reimburses Veterans for the provision of career transition services up to a lifetime maximum of $1,000 (taxes included). Through this funding, the Program aims to assist participants in obtaining the knowledge and skills necessary to prepare for and obtain employment post release.

This objective aligns with the mandate letter from the Prime Minister to the Minister of Veterans Affairs and Associate Minister of National DefenceFootnote 5, issued in November 2015, which states: “I expect you to ensure that Veterans receive the respect, support, care, and economic opportunities they deserve. You will ensure that we honour the service of our Veterans and provide new career opportunities.”

Subsequently the December 2015 Speech from the ThroneFootnote 6 stated: “In gratitude for the service of Canada’s veterans, the Government will do more to support them and their families.”

3.2 Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

The Career Transition Services Program objective is aligned with federal roles and responsibilities.

As further evidence of alignment, the evaluation team considered the VAC mandate, which stems from laws and regulations. In particular, the Department of Veterans Affairs Act charges the Minister of Veterans Affairs with the following responsibilities: "… the care, treatment, or re-establishment in civil life of any person who served in the Canadian Forces or merchant navy or in the naval, army or air forces or merchant navies of Her Majesty, of any person who has otherwise engaged in pursuits relating to war, and of any other person designated ... and the care of the dependents or survivors of any person referred to…”

VAC fulfils its mandate through programs, benefits and services authorized under the Canadian Forces Members and Veterans Re-establishment and Compensation Act (New Veterans Charter), the Pension Act and the Department of Veterans Affairs Act. The Department’s responsibility for re-establishment in civilian life begins after release from the CAF, although planning to support the transition is meant to begin prior to release (discussed further in Section 3.3).

One of the priorities identified in VAC’s 2015-16 Report on Plans and PrioritiesFootnote 7 is to provide caring and responsive service to Veterans and CAF members and their families, and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. The report discusses the Department’s strategic objectives, one of which is the “Financial, physical and mental well-being of eligible Veterans,” to which the CTS Program contributes.

VAC’s Five-Year Strategic Plan – Care, Compassion and Respect – lays out a new direction that will significantly change and improve how the Department serves and cares for Veterans.Footnote 8 The plan has three core objectives: being Veteran Centric, providing a Seamless Transition, and demonstrating Service Excellence. These objectives informed the evaluation.Footnote 9

3.3 Continued Need for the Program

There is a need for employment supports and transition services for releasing CAF members, but the Career Transition Services Program does not effectively respond to this need.

To evaluate relevance, the team assessed whether there is a demonstrable need for the Program; the extent to which the Program is meeting needs of eligible Veterans; and whether there is duplication or overlap with other career assistance/transition programs/providers and/or services.

Demonstrable Need

There is a need for employment supports and transition services for releasing CAF members.

Releasing CAF members have a variety of needs related to employment and transition, impacted by a number of factors including release type, years of service, branch of the Forces and occupation, physical and mental health, family situation, province of resettlement and economic climate at the time of release. The interplay of these factors and individual goals suggests the need for flexible employment supports and transition services.

The evaluation team found ample evidence of the need for employment supports and transition services. For example, the Program’s PMS indicates that during 2013-14, 2,151 non-medically releasing CAF personnel identified through their transition interview that they would not be retiring. More than half of them (1,123) had not yet found civilian employment, although 782 (70%) were actively seeking employment. Recent Life After Service Studies (LASS) findings, as presented in Labour-market Outcomes of VeteransFootnote 10, show that “unemployed Veterans had double the rate reporting difficulty adjusting to civilian life than employed Veterans.”

According to a May 2010 consultant reportFootnote 11 resulting from New Veterans Charter focus groups, when participants thought of their transition from the military to the civilian labour force, the most common employment or career-related goal was job stability. Other identified goals included flexibility in work hours, the ability to develop new skills/do something different, salary, a good balance between work and family life, and the ability to use/transfer existing skills.

VAC’s LASS has produced important insights relating to the Career Transition Services Program. In particular, a study entitled Effectiveness of Career Transition Services (2011)Footnote 12, based on an in-depth analysis of 2010 Survey on Transition to Civilian Life (STCL) data, was informative for this evaluation. Of the 3,154 Regular Force Veterans surveyed, 11% identified as having a high need for transition-employment services. These respondents were either unemployed at the time of the survey or experiencing low income (in 2009). A smaller proportion (5%) had a moderate need (i.e., employed at the time of the survey but dissatisfied with their job or main activity). The remaining 84% identified as having low to no need for CTS.

The studyFootnote 13 identified the following subgroups as more likely than the overall survey population to have a high need for transition-employment services: those released at younger age groups; those with fewer years of service; those released at lower ranks (recruits, privates and junior non-commissioned members [NCMs]); those released involuntarily or medically and those released from the Army. Males were slightly more likely than females to have a high need for transition-employment services. The greatest need for such assistance was among those involuntarily released (27%), compared to 11% for the overall survey population. The next greatest need was among those released at the youngest age group and those released as recruits, both at 21%, followed by Veterans with less than two years of service and Veterans released as privates at 20%.

Data relating to attendees at CAF Second Career Assistance Network (SCAN) seminars was also analyzed in the Effectiveness of Career Transition ServicesFootnote 14 study, with the following results: The 383 SCAN seminar attendees surveyed in 2010 were older, on average, than the overall releasing population, were more likely to have served for longer periods of time and were more likely to be medically releasing. In other words, the subpopulations identified above as most needing transition-employment services are not attending SCAN seminars, although these seminars are one of the main ways releasing members find out about CTS. Therefore, targeting assistance to those at higher risk may be necessary.

In its June 2014 report The Transition to Civilian Life of VeteransFootnote 15, the Senate Subcommittee on Veterans Affairs indicated that contrary to career management in civilian life, in which individuals regularly change jobs or seek new employment opportunities or even career paths, the military manages the careers of its members. Most recruits join the CAF at a relatively young age and they and their families are taken care of by the military while they are in uniform. Most members pursue long military careers, some of which span over several decades. Therefore, for many, military service has been the only job they have ever had. They have little or no experience with civilian job application processes, résumé development, job interview preparation, or how to market the numerous skills and trades acquired in the military to civilian employers. At the same time, many civilian employers lack an understanding of the military and do not fully grasp the potential value that Veterans can bring to their organizations.

As part of its field work, the evaluation team conducted interviews with 34 individuals, including CAF personnel, DND civilian employees, VAC staff, employment subject matter experts, and Employment and Social Development Canada officials. This research clearly demonstrated that some CAF members need employment supports and transition services; however, it was made equally clear that members need access to these services prior to release, especially since those who were not retiring reported their number one need was getting a job.

The CAF clearly recognizes the benefit of early engagement as the members’ first introduction to CTS is during a SCAN seminar which members are encouraged to attend five years prior to their release. Members are further encouraged to seek long-term planning services, offered by CAF, within their first term of service.

The existence of transition-employment programs in Allied countries also points to a need for such services among releasing military members, as discussed further in Subsection 4.3.3. Appendix B compares CTS with similar programs in the United Kingdom and the United States.

Program Responsiveness

The Career Transition Services Program has not met the needs of releasing Veterans.

Changes to the Program, implemented in 2012, clearly established that the CAF handles the members’ needs up to the day of release and then VAC takes over. However, this change resulted in a fundamental program design flaw. Each interviewee stressed that the most appropriate time to render assistance relating to the pursuit of employment is before the member becomes unemployed – timing which is not authorized under the amended legislation. Therefore, the Program is not currently meeting needs and uptake has decreased as a result. Table 3 below shows the drop in eligible Veterans between 2011-12 (581) and 2012-13 (27). This decrease could be attributable to the eligibility change (discussed above) as well as the termination of the third-party contract.

* As of January 1, 2013 the CTS program was redesigned from provision of services by a national external provider to provision of a maximum $1,000 grant payable directly to participants to assist in paying for career transition functions. This has contributed to the decrease in expenditures, starting in 2013-2014.

One of the core objectives of VAC’s Five-Year Strategic PlanFootnote 16 relates to a seamless transition from military to civilian life. Unfortunately, the 2012 changes to the Program, eliminating the possibility of releasing members to access CTS when it is most needed (i.e., prior to release), have actually created a seam where one did not originally exist for this Program. A subsequent change, effective July 2015, allows a releasing member to apply for the Program prior to release, but he or she still cannot access the benefit while still in uniform.

Results from the LASS study Effectiveness of Career Transition Services (2011)Footnote 17 showed that while those releasing at a younger age and with fewer years of service have a higher need for CTS, they are not participating in the Program. As Table 4 shows, there were 335 unique applications to the Program in the two-year period from April 1, 2013 to March 31, 2015, with application volumes being higher for older releasing members than those under 30 years of age. Those 335 applications resulted in a mere 40 VeteransFootnote 18 receiving reimbursement from the Program, perhaps because a large portion of them were filed in case the applicant wanted to use the services at a later date (application must be made within two years of release).

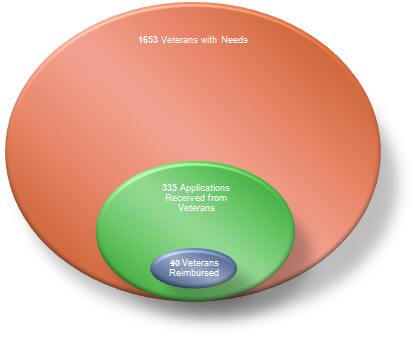

According to the study on Program effectivenessFootnote 19, 16% of the releasing CAF population have a high to moderate need for career employment assistance. Applying that percentage to the 10,334Footnote 20 Regular Force releases (10,004 of whom had VAC Transition Interviews) during the two-year period, reflected in Table 4 above, would suggest that 1,653 would require the Program’s services, well above the 335 who applied. In other words, only 20% of those who would appear to have a need for CTS applied, and of those, only 40 received reimbursement for services. These uptake numbers, as shown in Chart 1, reflect a Program that is not responsive to needs.

Chart 1 - CTS Applications and Reimbursements as a Proportion of Those with Potential High to Moderate Need

Chart 1 - CTS Applications and Reimbursements as a Proportion of Those with Potential High to Moderate Need

Duplication and Overlap

There is duplication and overlap between the Career Transition Services Program and other career assistance/transition programs, services and providers.

As indicated in VAC’s Labour Market Outcomes for VeteransFootnote 21 report, the Veterans Transition Advisory Committee identified 18 employment assistance programs provided by government and non-government organizations (see Appendix C). One program focuses on fundraising with no employment services. Five programs are for disabled Veterans. Four programs were found to be province specific. Two programs work with employers to encourage the hiring of Veterans. Six programs were found to provide employment services, on a national basis, to Veterans with or without disabilities. Table 5 illustrates the number of programs by various providers and sectors.

The Canadian Armed Forces Transition ServicesFootnote 22 program offers individual transition assistance as well as individual counselling to each still-serving member. It includes seminars, workshops and access to a network of information to aid in long-term planning and seamless career transitions. Career Transition Workshops, typically offered by Base/Wing Personnel Selection Officers, cover but are not limited to interest and skill self-assessment, resume writing, job search strategies and interview techniques. While aspects of this program are available to eligible CAF members throughout their careers, some services may only be offered to those transitioning to civilian life.

CAF Learning and Career Centres (LCCs), located on 14 Bases/Wings and staffed by civilian learning advisors, provide career services which appear to duplicate those being offered by VAC through its CTS Program. The learning advisors interviewed as part of the evaluation’s field work indicated a willingness to provide services to CAF members. As an illustration of duplication, while it was in place, the third-party contractor would be providing information in one part of the building at the same time as the LCC was providing the same information in another. Subsequent to the field work, VAC learned that the CAF is reviewing the LCCs and their various programs.

In fall 2014, the Government of Canada announced that it would invest up to $15.8 million to fund a partnership between VAC and DND to provide medically-releasing Veterans and their families access to Military Family Resource Centres (MFRCs)Footnote 23 for two years following release to support their transition to civilian life. To assist in that transition, the MFRCs are providing enhanced information and referral services. This partnership is currently operating as a pilot project at seven sites. Data will be collected at the pilot sites to determine if access for medically-releasing Veterans and their families should be extended to all MFRC sites, if it should be extended to all releasing/released Veterans, or if access should be discontinued. Extending it to all releasing members (i.e., medical releases and voluntary releases) would create considerable duplication with the CTS Program.

Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) renewed its Labour Market Agreements (LMAs) with the provinces and territories on April 1, 2014; they are now due to expire on March 31, 2020. As part of the new LMAs, the federal government reaffirmed its Economic Action Plan commitment to transform skills training in Canada through the introduction of the Canada Job Grant which would directly involve employers. Other agreements between the provinces and territories are the Canada Job Fund Agreement, LMAs for Persons with Disabilities, training for older workers (ages 54-65) and the Labour Market Development Agreement (LMDA)Footnote 24. Through these various agreements, Canada downloads to provinces and territories responsibility for the design and delivery of labour market programs to support the creation of a skilled, productive, mobile and adaptable labour force.

Some CAF members leaving at a young age might qualify for services under the Job Fund Agreement or under the LMDA, after the expiry of the Employment Insurance waiting period and completion of any severance package time limits.

In addition to the Career Transition Services Program, the subject of this evaluation, VAC also offers Vocational Rehabilitation services as part of its Rehabilitation Program under the New Veterans Charter. Although eligibility requirements differ, each program offers some career assistance servicesFootnote 25.

In its 2014 reportFootnote 26, the Senate Subcommittee summarizes “… a growing number of resources are now available to assist releasing members of the CAF with their transition to the civilian workforce, and the situation is constantly improving.” While this abundance of resources does provide more options to releasing members, it also points to considerable overlap and duplication.