Joined

1950

Postings

- HMCS Iroquois

- Hamilton, ON

- Vancouver, BC

- St. Hubert, Quebec

Deployments

- Korean War, 1952

Residential school survivor

Throughout his life, Russ Moses refused to be defined by his residential school experience.

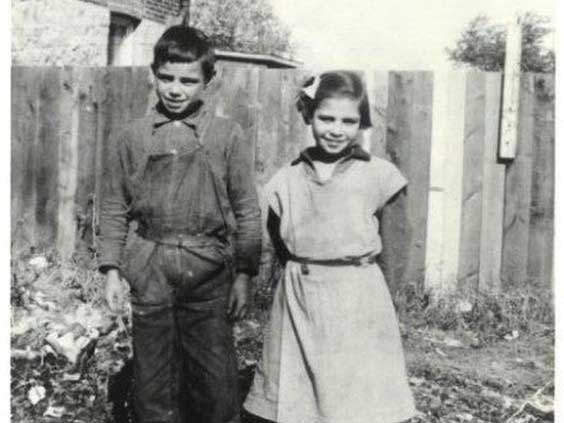

A member of the Delaware band from the Six Nations of the Grand River Territory, he attended the Mohawk Institute in Brantford, Ontario from 1942 to 1947, arriving when he was just 8 years old. His younger sister and an older brother were also there. The three children endured harsh conditions and inhumane treatment, while receiving a substandard education that left few career options.

Like many of his peers, he considered the military “a way up and a way out of his childhood circumstances,” according to his son, John. At age 18, he joined the Royal Canadian Navy, beginning a 15-year career in the Canadian Armed Forces.

“He wanted to put as much distance both geographically and otherwise between himself and the Mohawk Institute,” says John.

Joining the military

During his first training operation aboard HMCS Ontario, he travelled around the globe, fulfilling his dream of seeing the world. With the Korean War raging overseas, he deployed to Korea on the HMCS Iroquois and was on board when the destroyer came under enemy fire on October 2, 1952. Three sailors were killed and many others were wounded – the first and only navy casualties during the war.

He was proud of his Korean War service.

“He was proud of his Korean War service,” says John. “Even though he was engaged in war and combat, he said the food was better and the discipline was less than it was in residential school. He had no problems at all adapting to naval life.”

Russ released from the navy in 1955 and briefly returned to the Six Nations reserve, where he met and married his wife Helen, a registered nurse. Shortly after, he re-enlisted, this time in the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF). Over the next 10 years, he served as a safety equipment technician in postings across the country, maintaining equipment for RCAF pilots and search and rescue specialists.

A new career

In 1965, he declined a posting at Canadian Forces Base Lahr in Germany to apply for a position in the federal public service, which was looking to hire Indigenous people to work on Indigenous issues.

“He joined the federal public service just as they were ramping up for the centennial celebrations in 1967,” explains John. “He was the Deputy Commissioner General of the Indians of Canada Pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal.”

The International and Universal Exposition of 1967 – known as Expo 67 – was the most successful world’s fair of the 20th century, drawing more than 50 million visitors from around the world, including diplomats and heads of state. The Indians of Canada Pavilion, one of 90 pavilions at the exhibition, showcased Indigenous art and cultural artifacts that brought to light some of the issues facing Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

“He was very proud of that Pavilion, [which] was a huge watershed in terms of Indigenous self-representation before national and global audiences,” says John.

While the Pavilion was one of the highlights of Russ’s public service career, it wasn’t his only lasting contribution to Indigenous self-representation. His own words would one day be part of a national conversation about reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples.

Sharing his story

“When he left the air force in 1965 to start in the federal public service, he was asked by his new boss to offer a summary of his views on residential schools,” explains John.

The result was a memoir about his experience at the Mohawk Institute. Though only five page long, it’s an honest and unflinching look into daily life at one of Canada’s residential schools – describing the brutal conditions of being underfed, overworked and devalued as an Indigenous child.

This situation divides the shame amongst the Churches, the Indian Affairs Branch and the Canadian public.

“Our formal education was sadly neglected,” Russ writes. “When a child is tired, hungry, lice infested and treated as sub-human, how in heaven’s name do you expect to make a decent citizen out of him or her[?]”

Russ spent the rest of his career in various public service positions, using his remarkable people skills in mediations with Indigenous groups on behalf of the government. Meanwhile, his memoir was nearly forgotten, until researchers from the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples found it in the national archives in the early 1990s and tracked him down.

At their request, he reread the document for the first time in years. “He said: I wouldn’t change a single thing…Everything I wrote back then still stands,” says John.

More than 55 years later, Russ’s words about the legacy of residential schools in Canada are as powerful as ever:

“This situation divides the shame amongst the Churches, the Indian Affairs Branch and the Canadian public…When I was asked to do this paper I had some misgivings, for if I were to be honest, I must tell of things as they were and really this is not my story, but yours.”

Carrying on his legacy

Since Russ passed away in 2013, John has made dozens of presentations on his father’s memoir. Like his father, he’s also a Veteran of the Canadian Armed Forces, where he served as a communicator research operator, and a dedicated public servant. He is currently a lab manager at the Canadian Conservation Institute, where he helps preserve the history of Canada’s Indigenous peoples – carrying on the legacy his father began at Expo 67.

Asked about his commitment to continue sharing his father’s residential school experience, his answer is simple: “It’s a means of keeping my father’s memory alive.”

With courage, integrity and loyalty, Russ and his son, John have left their mark. They are two of our Canadian Veterans. Discover more stories.

If you a Veteran, family member or caregiver in need of mental health support, the VAC Assistance Service is available to you 24/7, 365 days a year at no cost. Call "1-800-268-7708 to speak to a mental health professional right now.