He Had a Code of Honour and Wasn’t Going to Commit Me to Die

Heroes Remember

He Had a Code of Honour and Wasn’t Going to Commit Me to Die

Transcript

Description

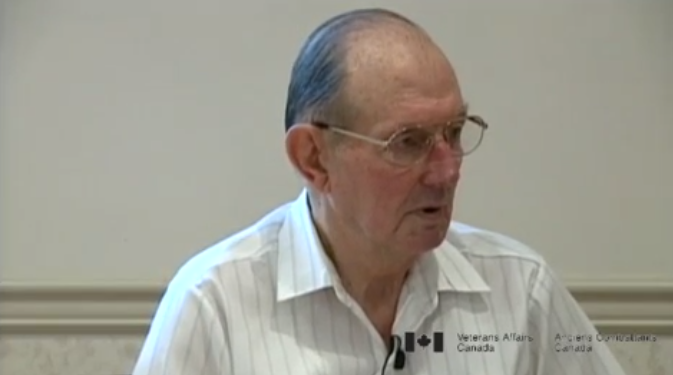

Mr. Barton describes both compassionate and brutal treatment by POW camp personnel.

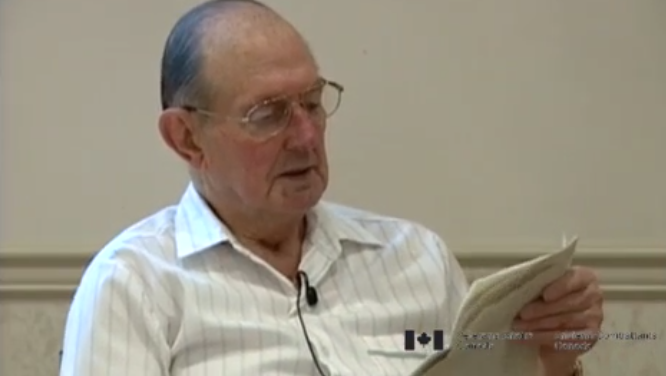

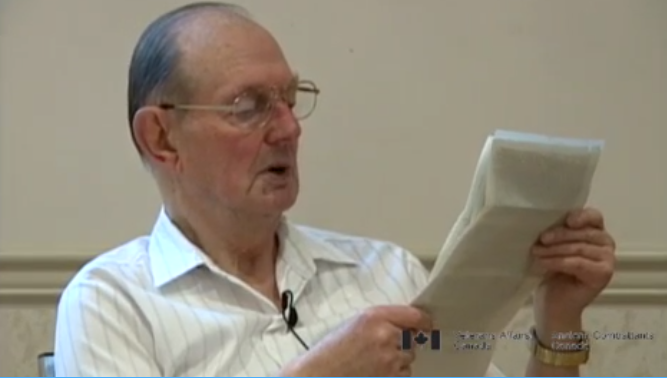

Thomas Barton

Thomas Barton was born in Victoria, British Columbia, on June 8, 1920. His father worked as the Deputy Registrar with the Supreme Court in Victoria. After attending high school, Mr. Barton worked for the Victoria Times, a local newspaper before joining the Underwood Typewriter Company. He enlisted in September, 1939 as a staff clerk. Upon reaching Hong Kong, Mr. Barton was attached to Brigade Headquarters. Despite minimal training, he was compelled by heavy Canadian losses to assume a combat role. After the surrender of Hong Kong, he spent time in North Point and Sham Shui Po, POW camps in the colony, and was then sent to the Japanese labour camps, Sendai being the last. Mr. Barton feels that the Canadian Government was remiss in not recognizing the Veterans of Hong Kong much sooner than it did.

Meta Data

- Medium:

- Video

- Owner:

- Veterans Affairs Canada

- Duration:

- 3:54

- Person Interviewed:

- Thomas Barton

- War, Conflict or Mission:

- Second World War

- Location/Theatre:

- Japan

- Battle/Campaign:

- Hong Kong

- Branch:

- Army

- Occupation:

- Military Staff Clerk

Related Videos

- Date modified: