Entitlement Eligibility Guideline (EEG)

Date created: 31 March 2025

ICD-11 code: CA23

VAC medical code: 00829 Asthma, asthmatic bronchitis, reactive airway disease

This publication is available upon request in alternate formats.

Full document – PDF Version

Definition

Asthma is a group of respiratory conditions characterized by airway inflammation, bronchial hyperresponsiveness, and reversible airflow obstruction. These reactions occur in response to various stimuli and are characterized by symptoms of wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and coughing that vary over time and in intensity.

For the purposes of this entitlement eligibility guideline (EEG), equivalent diagnoses to asthma include:

- allergic asthma

- non-allergic asthma

- exercise-induced bronchoconstriction/exercise-induced asthma

- occupational asthma

- eosinophilic asthma

- asthma with fixed airflow obstruction

- reactive airway disease

- asthmatic bronchitis.

Diagnostic standard

Diagnosis by a qualified physician (respirologist, allergist/immunologist, family physician), or nurse practitioner is required.

Confirmation of asthma may involve investigations as described below such as spirometry to evaluate airflow obstruction and reversibility, peak expiratory flow monitoring to assess variability in airway obstruction, or a bronchodilator reversibility test to demonstrate responsiveness to asthma medication.

- Spirometry is used to determine the presence of obstruction, and degree of reversibility (generally defined as combination of increase in forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1] > 200 mL and ≥ 12% from baseline after inhalation of short-acting bronchodilator).

- Peak expiratory flow identifies variability in lung function. A change over 10% in readings between morning and evening, or following bronchodilator administration, or a positive response to asthma medication, further supports an asthma diagnosis.

- A bronchodilator reversibility test involves clinical observation over time to diagnose asthma with a repeated resolution of the symptoms of asthma when treated with bronchodilators as determined by a clinician observer.

Additional testing to confirm the diagnosis may include:

- Bronchial challenge test (inhaling methacholine, mannitol or histamine), to identify airway hyperresponsiveness. A negative bronchial challenge test makes the diagnosis of asthma unlikely.

- Allergy test, to detect allergen sensitivities contributing to asthma.

- Exhaled nitric oxide test, to measure airway inflammation.

Anatomy and physiology

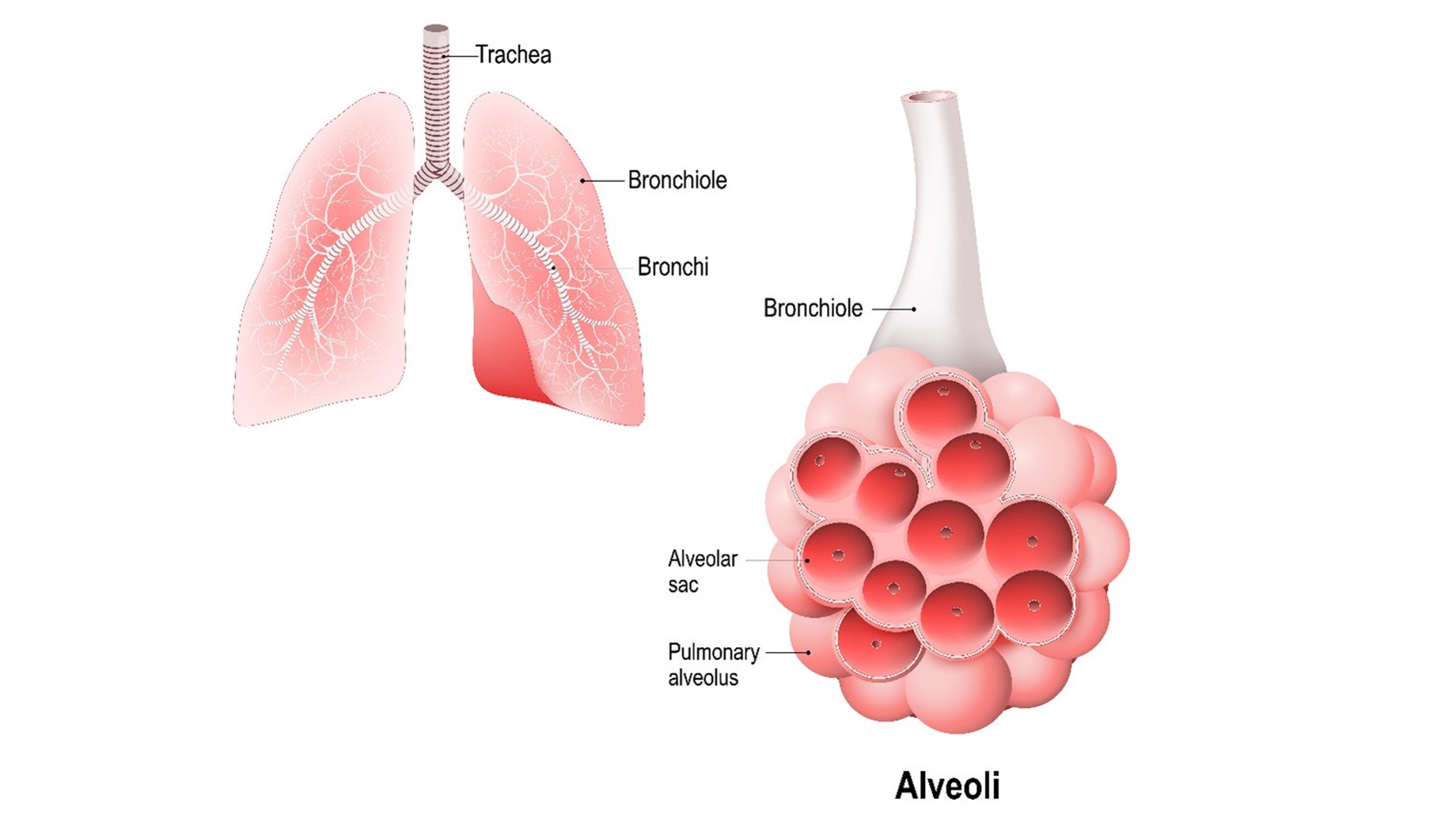

Asthma is a condition that involves the airways and lungs. The airways and lungs (Figure 1: Lung and alveoli anatomy) consists of the trachea that divides into smaller bronchi and then into bronchioles, culminating in tiny sacs termed alveoli where gas exchange occurs. The airways' smooth muscle layer and surrounding inflammatory cells influence the severity of asthma.

Figure 1: Lung and alveoli anatomy

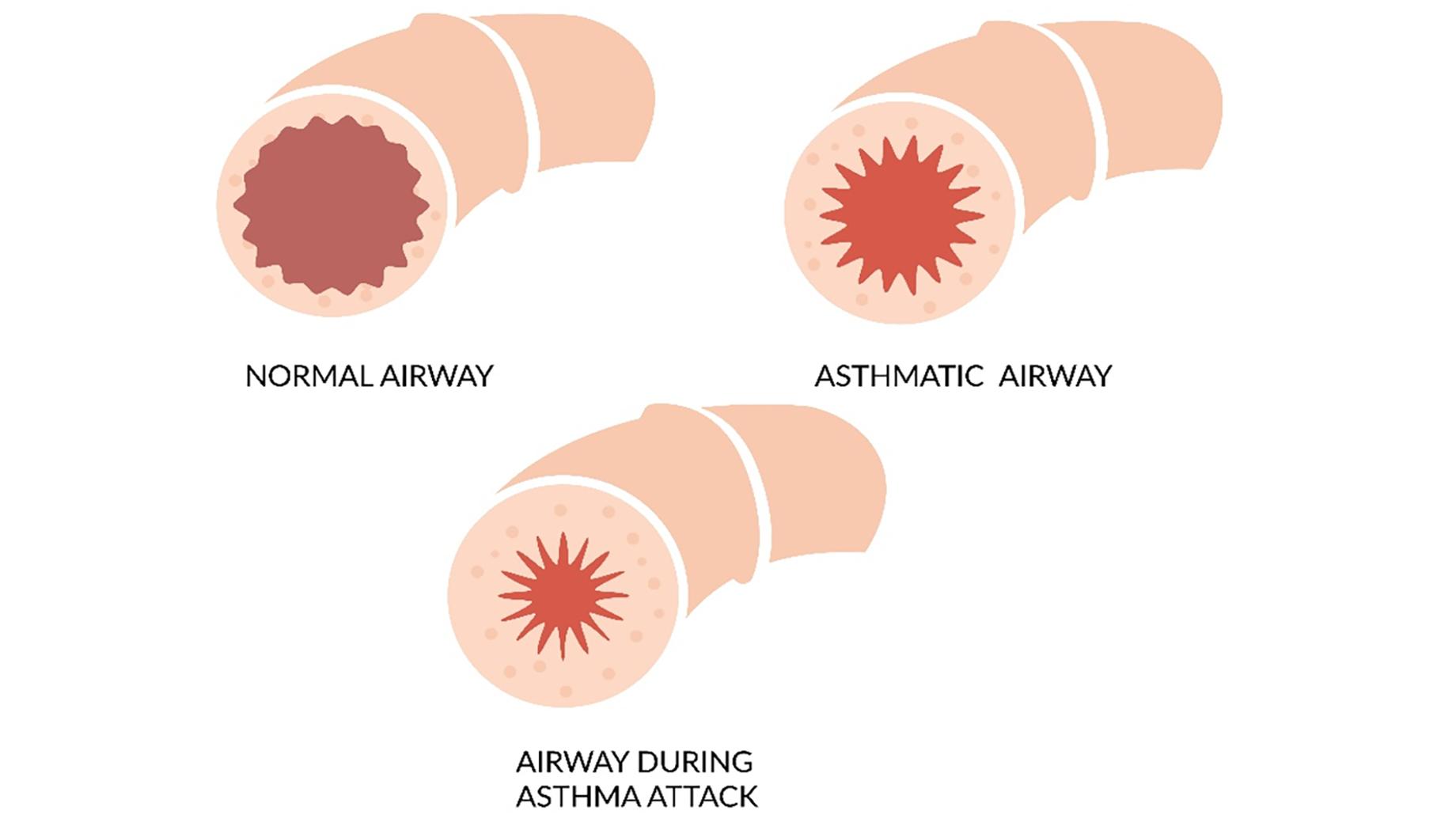

The airways and lungs in a person with asthma are hyperresponsive, meaning they react more strongly and easily than normal to various triggers. This hyperresponsiveness causes narrowing of the airways resulting in episodes of tightness, coughing, wheezing, and breathlessness (Figure 2: Airway patency). Inflammation leads to swelling and excess mucus production, further narrowing the airways. Over time, chronic inflammation can cause structural changes, known as airway remodeling, making the airways permanently narrower.

Figure 2: Airway patency

The cause of asthma is considered to be due to a combination of genetic and environmental factors. There are several types of asthma with distinct triggers leading to development of this medical condition as described below. Each type of asthma involves specific pathways and reactions within the lungs and airways, but all may result in reduced airflow and difficulty breathing. For Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC) purposes, triggers may be considered to establish a relationship between service and the development of asthma.

Allergic asthma occurs when the immune system is triggered by external allergens such as pollen, dust mites, mold, or pet dander, leading to airway inflammation. This reaction is mediated by Immunoglobulin E (IgE), releasing inflammatory substances such as histamine causing airway narrowing and increased mucus production. It is often associated with a history of allergic reactions.

Non-allergic asthma is not related to allergens, and may be triggered by various non-allergic factors such as cold air, exercise, significant level of stress, viruses or respiratory infections, smoke or exposure to airborne particulate matter, particularly particles 10 microns or less in diameter (PM10). The exact mechanism is less understood but involves the direct activation of the airways' smooth muscles and inflammatory response without the allergic mediation by IgE.

Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (EIB) is airway narrowing triggered during or after exercise. It is believed to be the result of cooling and water loss in the airway lining during heavy breathing, triggering smooth muscle contraction. This response is mediated by the release of inflammatory substances from the mast cells, leading to bronchial constriction. While EIB can occur in individuals with asthma, it can also be present in people without chronic asthma.

Eosinophilic asthma is a subtype of asthma characterized by a heightened presence of eosinophils within the airways, leading to chronic inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness. Eosinophils are a type of white blood cell that may be present in the blood, sputum, or both, and is often associated with more severe symptoms. Unlike allergic asthma, eosinophilic asthma may not be directly triggered by allergens and can occur in individuals without a history of allergic reactions.

Asthma with fixed airflow obstruction is a type of asthma resulting in a component of airway obstruction that is not fully reversible despite asthma treatment. Asthma with fixed airway obstruction may resemble chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in symptoms and diagnostic presentation.

Asthma and COPD have overlapping symptoms, but their management differs significantly, underscoring the need for accurate diagnosis. The "Asthma-COPD overlap" describes patients with features of both conditions. Distinct from asthma, COPD is characterized by neutrophilic inflammation leading to chronic symptoms and progressive airflow obstruction.

For this symptom presentation, consultation with a disability consultant and/or medical advisor is recommended.

Note: Occupational asthma is airway inflammation triggered by exposure to substances encountered in the workplace with symptoms improving when away from the work environment. It may be allergic or non-allergic asthma.

Clinical features

Asthma is a chronic respiratory condition with symptoms and severity that vary widely among individuals and within the same individual over time. It can present with mild, infrequent symptoms, or severe, persistent coughing, wheezing, and acute exacerbations. Asthma's impact on physical activity and daily life can range from mild to severe.

Allergic asthma is typically triggered by exposure to specific allergens, leading to an immediate reaction that includes sneezing, itchy eyes, and a rapid onset of breathing difficulties.

Non-allergic asthma manifests without a clear allergic trigger and may present more unpredictably in the presence of non-allergic triggers. The response to standard asthma treatments may vary in this type of asthma.

Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction involves coughing, wheezing, or shortness of breath during or after exercise. Symptoms usually peak within 5-10 minutes after exercise begins and can take up to 30 minutes to resolve without treatment. EIB can occur in individuals with and without asthma, particularly affecting those who are frequently exposed to cold, dry air, and environmental pollutants during exercise. EIB can be the first presentation of adult-onset asthma.

Eosinophilic asthma presents with severe, persistent respiratory symptoms such as wheezing, shortness of breath, and frequent exacerbations, often resistant to standard asthma therapies.

For VAC purposes, there are four clinical presentations of asthma for consideration of entitlement:

- First-time asthma symptoms triggered by an exposure: Individuals who experience their first asthma symptoms due to a service-related exposure, leading to an acute asthmatic episode within 24 hours of the exposure and necessitates medical treatment.

- Re-emergence of childhood asthma due to an exposure: Individuals with diagnosed or probable asthma during childhood requiring no further treatment beyond the age of 13, who experience symptoms following a service-related exposure. The service-related exposure leads to an acute asthmatic episode within 24 hours and requires treatment. For VAC purposes, this is considered a new clinical onset, rather than an aggravation, of asthma.

- Pre-existing asthma unchanged by an exposure: Individuals with pre-existing well-controlled asthma, requiring intermittent treatment, who experience an acute asthmatic episode within 24 hours of a service-related exposure. In this scenario, the frequency and severity of asthma symptoms remain unchanged from before service. This indicates no permanent aggravation of asthma as a result of the service-related exposure.

- Aggravation of pre-existing asthma due to an exposure: Individuals with asthma symptoms controlled by intermittent treatment who experience a permanent worsening of their condition following a service-related exposure. This is evidenced by an acute asthmatic episode within 24 hours of a service-related exposure requiring treatment and a noticeable chronic increase in the frequency and/or severity of symptoms. This worsening may be demonstrated by, but not limited to, a significant increase in dosage, change, or addition of medication, and/or hospital admissions compared to before the service-related exposure. For VAC purposes this is considered a permanent aggravation of a pre-existing asthma.

Asthma exhibits distinct patterns of prevalence and severity across sexes and life stages, with a higher prevalence in males during childhood that shifts to greater prevalence and severity in females after puberty. This transition is influenced by sex hormones, which significantly impact asthma pathogenesis in females during puberty, the menstrual cycle, and pregnancy.

Entitlement considerations

In this section

Section A: Causes and/or aggravation

For VAC entitlement purposes, the following factors are accepted to cause or aggravate the conditions included in the Definition section of this EEG, and may be considered along with the evidence to assist in establishing a relationship to service. The factors have been determined based on a review of up-to-date scientific and medical literature, as well as evidence-based medical best practices. Factors other than those listed may be considered, however consultation with a disability consultant or medical advisor is recommended.

The timelines cited below are for guidance purposes. Each case should be adjudicated on the evidence provided and its own merits.

Note: Evidence of a trigger causing a reversible episode of asthma, without evidence of ongoing treatment, is not sufficient for entitlement purposes.

Factors

- Having an exposure to an environmental irritant, triggering within 24 hours, the clinical onset or aggravation of an acute asthmatic episode and requires ongoing or recurrent treatment for a minimum of six months. Environmental irritants may include, but are not limited to:

- Allergic stimuli: Exposures that trigger an immune response leading to the asthma condition. Examples include pollen, dust and dust mites, or mold.

- Non-allergic stimuli: Exposures that can irritate the respiratory system without initiating an immune response. This category of triggers encompasses irritants such as, but not limited to:

- airborne substances such as diesel exhaust fumes, gases, halogenated derivatives, solvents, sprays, acids, alkalis, biocides, and from burning of materials such as chemicals, paint, metal, petroleum and lubrication products, plastics, Styrofoam, rubber, wood

- benzene and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) from jet fuel

- exposure to airborne particulate matter, particularly particles 10 microns or less in diameter (PM10)

- second-hand tobacco smoke in a confined space

- cold air.

Note:

- For VAC purposes, entitlement and/or aggravation from exposure to secondhand smoke requires the client to be a non-tobacco smoker.

- At the time of publication, the health-related expert opinion and scientific evidence indicates that exposure to asbestos or radon gas is not associated with the clinical onset or aggravation of asthma.

- Having a viral, or non-viral, respiratory tract infection within 24 hours before the clinical onset or aggravation of asthma.

- Having exercise-induced bronchial hyperresponsiveness within 24 hours before the clinical onset or aggravation of asthma.

- Using medication from the specified list below within 24 hours of the clinical onset or aggravation of asthma.

These medications include, but are not limited to, the following:

- acetylsalicylic acid (ASA)

- nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs)

- beta adrenergic blocking agents (non-selective).

Note:

- Individual medications may belong to a class of medications. The effects of a specific medication may vary from the class. The effects of the specific medication should be considered.

- If it is claimed a medication resulted in the clinical onset or aggravation of asthma, the following must be established:

- The medication was prescribed to treat an entitled condition.

- The individual was receiving the medication at the time of the clinical onset or aggravation of the asthma.

- The current medical literature supports the medication can result in the clinical onset or aggravation of asthma.

- The medication use is long-term, ongoing, and cannot reasonably be replaced with another medication or the medication is known to have enduring effects after discontinuation.

- Having a diagnosed gastroesophageal reflux disease at the time of the clinical onset or aggravation of asthma.

- Inability to obtain appropriate clinical management of asthma.

Section B: Medical conditions which are to be included in entitlement/assessment

Section B provides a list of diagnosed medical conditions which are considered for VAC purposes to be included in the entitlement and assessment of asthma.

- Chronic or recurrent respiratory infection

- Chronic or recurrent bronchiolitis

Section C: Common medical conditions which may result, in whole or in part, from asthma and/or its treatment

Section C is a list of conditions which can be caused or aggravated by asthma and/or its treatment. Conditions listed in Section C are not included in the entitlement and assessment of asthma. A consequential entitlement decision may be considered where the individual merits and the medical evidence of the case support a consequential relationship.

Conditions other than those listed in Section C may be considered; consultation with a disability consultant or medical advisor is recommended.

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Chronic obstructive lung disease (COLD)

- Chronic bronchitis

- Bronchiectasis

- Emphysema

Links

Related VAC guidance and policy:

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Pain and Suffering Compensation – Policies

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police Disability Pension Claims – Policies

- Dual Entitlement – Disability Benefits – Policies

- Establishing the Existence of a Disability – Policies

- Disability Benefits in Respect of Peacetime Military Service – The Compensation Principle – Policies

- Disability Benefits in Respect of Wartime and Special Duty Service – The Insurance Principle – Policies

- Disability Resulting from a Non-Service Related Injury or Disease – Policies

- Consequential Disability – Policies

- Benefit of Doubt – Policies

References as of 31 March 2025

Aggarwal, B., Mulgirigama, A., & Berend, N. (2018). Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction: Prevalence, pathophysiology, patient impact, diagnosis and management. Npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine, 28(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-018-0098-2

Australian Government Repatriation Medical Authority. (2021) Statement of Principles concerning Asthma (Balance of Probabilities) (No. 32 of 2021). SOPs - Repatriation Medical Authority

Australian Government Repatriation Medical Authority. (2021) Statement of Principles concerning Asthma (Reasonable Hypothesis) (No. 31 of 2021). SOPs - Repatriation Medical Authority

Chatkin, J., Correa, L., & Santos, U. (2022). External Environmental Pollution as a Risk Factor for Asthma. Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology, 62(1), 72–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-020-08830-5

Chowdhury, N. U., Guntur, V. P., Newcomb, D. C., & Wechsler, M. E. (2021). Sex and gender in Asthma. European Respiratory Review, 30(162), 210067. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0067-2021

Committee on the Respiratory Health Effects of Airborne Hazards Exposures in the Southwest Asia Theater of Military Operations, Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, Health and Medicine Division, & National Academies, Sciences, and Engineering. (2020). Respiratory Health Effects of Airborne Hazards Exposures in the Southwest Asia Theater of Military Operations (p. 25837). National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25837

Global Initiative for Asthma (July, 2023). Global strategy for Asthma management and prevention. https://ginAsthma.org/2023-gina-main-report/

Krefft, S. D., & Zell-Baran, L. M. (2023). Deployment-Related Respiratory Disease: Where Are We? Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 44(03), 370–377. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-1764407

Lawrence, K. G., Niehoff, N. M., Keil, A. P., Braxton Jackson, W., Christenbury, K., Stewart, P. A., Stenzel, M. R., Huynh, T. B., Groth, C. P., Ramachandran, G., Banerjee, S., Pratt, G. C., Curry, M. D., Engel, L. S., & Sandler, D. P. (2022). Associations between airborne crude oil chemicals and symptom-based Asthma. Environment International, 167, 107433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2022.107433

LoMauro, A., & Aliverti, A. (2018). Sex differences in respiratory function. Breathe, 14(2), 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.000318

Mattila, T., Santonen, T., Andersen, H. R., Katsonouri, A., Szigeti, T., Uhl, M., Wąsowicz, W., Lange, R., Bocca, B., Ruggieri, F., Kolossa-Gehring, M., Sarigiannis, D. A., & Tolonen, H. (2021). Scoping Review—The Association between Asthma and Environmental Chemicals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18031323

McCracken, J. L., Veeranki, S. P., Ameredes, B. T., & Calhoun, W. J. (2017). Diagnosis and Management of Asthma in Adults: A Review. JAMA, 318(3), 279. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.8372

Morris, M. J., Walter, R. J., McCann, E. T., Sherner, J. H., Murillo, C. G., Barber, B. S., Hunninghake, J. C., & Holley, A. B. (2020). Clinical Evaluation of Deployed Military Personnel With Chronic Respiratory Symptoms. Chest, 157(6), 1559–1567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2020.01.024

Mosnaim, G. (2023). Asthma in Adults. New England Journal of Medicine, 389(11), 1023–1031. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp2304871

Porsbjerg, C., Melén, E., Lehtimäki, L., & Shaw, D. (2023). Asthma. The Lancet, 401(10379), 858–873. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02125-0

Rodriguez Bauza, D. E., & Silveyra, P. (2020). Sex Differences in Exercise-Induced Bronchoconstriction in Athletes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19), 7270. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197270

Rogliani, P., Cavalli, F., Ritondo, B. L., Cazzola, M., & Calzetta, L. (2022). Sex differences in adult Asthma and COPD therapy: A systematic review. Respiratory Research, 23(1), 222. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-022-02140-4

Rose, C. S. (2012). Military Service and Lung Disease. Clinics in Chest Medicine, 33(4), 705–714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccm.2012.09.001

Silveyra, P., Fuentes, N., & Rodriguez Bauza, D. E. (2021). Sex and Gender Differences in Lung Disease. In Y.-X. Wang (Ed.), Lung Inflammation in Health and Disease, Volume II (Vol. 1304, pp. 227–258). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-68748-9_14

Slater, M., Perruccio, A. V., & Badley, E. M. (2011). Musculoskeletal comorbidities in cardiovascular disease, diabetes and respiratory disease: The impact on activity limitations; a representative population-based study. BMC Public Health, 11(1), 77. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-77

Van De Graaff, J., & Poole, J. A. (2022). A Clinician’s Guide to Occupational Exposures in the Military. Current Allergy and Asthma Reports, 22(12), 259–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-022-01051-0

Veterans Affairs Canada (2024). Lung and Alveoli Anatomy. License purchased for use from https://www.123rf.com/photo_170395080_pulmonary-alveolus-alveoli-trachea-and-bronchiole-in-the-lungs-vector-illustration.html

Veterans Affairs Canada (2024). Airway Patency. License purchased for use from https://www.123rf.com/photo_157065694_asthma-blocked-airway-icon-as-eps-10-file.html

World Health Organization. (2019). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th Revision). https://icd.who.int/

World Health Organization (2023). A visualized overview of global and regional trends in the leading causes of death and disability 2000-2019. https://www.who.int/news/item/09-12-2020-who-reveals-leading-causes-of-death-and-disability-worldwide-2000-2019

Yang, C. L., Hicks, E. A., Mitchell, P., Reisman, J., Podgers, D., Hayward, K. M., Waite, M., & Ramsey, C. D. (2021). Canadian Thoracic Society 2021 Guideline update: Diagnosis and management of Asthma in preschoolers, children and adults. Canadian Journal of Respiratory, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, 5(6), 348–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/24745332.2021.1945887

Zhang, G.-Q., Özuygur Ermis, S. S., Rådinger, M., Bossios, A., Kankaanranta, H., & Nwaru, B. (2022). Sex Disparities in Asthma Development and Clinical Outcomes: Implications for Treatment Strategies. Journal of Asthma and Allergy, Volume 15, 231–247. https://doi.org/10.2147/JAA.S282667