Entitlement Eligibility Guideline (EEG)

Date created: 31 March 2025

ICD-11 codes: FA8Z, FA80.9, FA81.Z, FA84.Z, ME84.2, ME84.20, ME84.2Y, ME84.2Z, ME86.2, ME86.21, ME86.22, ME86.2Y, ME86.2Z, NB53.5, 8B93.Y

VAC medical codes:

01413

Lumbar disc disease, osteoarthritis lumbar spine, spondylosis lumbar spine, facet joint syndrome, osteoarthritis facet joints.

72450

Chronic mechanical low back pain, chronic mechanical lumbar pain/strain

This publication is available upon request in alternate formats.

Full document – PDF Version

Definition

For the purposes of this entitlement eligibility guideline (EEG), the following conditions are included:

- Degenerative conditions of the lumbar spine include:

- degenerative disc disease of the lumbar spine

- lumbar disc disease includes, but is not limited to:

- intervertebral disc prolapse of the lumbar spine

- intervertebral disc herniation of the lumbar spine.

- osteoarthritis/osteoarthrosis (OA) of the lumbar spine includes, but is not limited to:

- osteoarthritis of the lumbar spine

- osteoarthritis of the facet joints of the lumbar spine

- lumbar facet syndrome

- lumbar spondylosis.

Note: The terms osteoarthritis and osteoarthrosis are used interchangeably in the medical community. For the purposes of this EEG, these terms are considered synonymous and will be hereinafter called OA.

- Soft tissue conditions of the lumbar spine include, but are not limited to:

- chronic mechanical lumbar back pain

- chronic mechanical low back pain

- chronic lumbar sprain

- chronic lumbar strain

- chronic myofascial pain of the lumbar region.

Note: Cauda equina syndrome is not included in entitlement and assessment of lumbar spine conditions and requires a separate consequential entitlement decision.

Diagnostic standard

A diagnosis from a qualified physician, nurse practitioner or physician assistant (within their scope of practice) is required.

A careful history and physical examination are essential components in the diagnostic evaluation of lumbar spine conditions. Low back pain is often not a single disorder and can be caused by multiple pathophysiologic mechanisms affecting the region of the lower spine and surrounding structures. The cause of chronic low back pain can often be differentiated based on a patient’s history, physical exam, and imaging.

The initial evaluation of low back pain should include screening questions about symptoms that point to a progressive or unstable cause for pain such as cancer, infection, trauma, and neurologic compromise. Among patients who present with low back pain, less than 1% will have a serious systemic etiology.

The history should include location, duration, and severity of pain as well as details of any prior back pain. The presence of additional red flag symptoms (such as weight loss, fever, sweats, history of malignancy, neurologic symptoms, bowel or bladder symptoms) are also evaluated to assess the need for imaging and further evaluation.

Diagnostic imaging abnormalities are common, especially with age, and can be difficult to correlate with symptoms. The main imaging methods to evaluate back pain are magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computerized tomography (CT), and plain radiographs (X-ray).

Imaging is reserved for patients with severe or progressive neurologic deficits or when serious underlying conditions are suspected. Supporting documentation should be as comprehensive as possible.

Note: Lumbar disc disease and OA of the lumbar spine are clinical diagnoses. Diagnostic imaging may be helpful but is not required to establish the diagnosis, and the diagnosis cannot be made based on imaging studies alone. Radiographic findings of degenerative changes at the time of the onset of symptoms do not indicate a pre-existing clinical condition of lumbar disc disease or OA of the lumbar spine.

Anatomy and physiology

The spinal region consists of soft tissues, bony elements, intervertebral discs, and nerve tissue.

Soft tissues of the lumbar spinal region

The soft tissues of the lumbar spine include the muscles, tendons, and ligaments.

There are many layers of muscles in the lumbar spinal region controlling the movement of the low back. Each muscle is attached to a bone with a tendon. A ligament connects bones and stabilizes joints.

The bony elements of the lumbar spine

The spine is composed of 33 individual bones called vertebrae (Figure 1: Human vertebrae anatomy). Each vertebra resembles a building block. The vertebrae are stacked to form a column down the spine, with an intervertebral disc between each vertebra. The spine is also referred to as the spinal column or vertebral column.

Figure 1: Human vertebrae anatomy

The human spine is composed of five main regions, listed from top to bottom: the cervical spine (7 vertebrae), thoracic spine (12 vertebrae), lumbar spine (5 vertebrae), sacrum (5 fused vertebrae), and the coccyx (3–5 fused vertebrae). Vertebrae mainly consist of semi-circles of bone (vertebral body) separated by intervertebral discs. These discs have a tough outer layer (annulus fibrosus) and a gel-like inner core (nucleus pulposus). Each vertebra features projections for muscle attachment. Transverse processes are lateral projections that serve as attachment points for the back muscles, while spinous processes are posterior projections felt through the skin of the spine. The inside of the spinal cord contains white matter (transmits signals); grey matter (processes information); dura mater (outer membrane); and spinal nerves (attaches spinal cord to the body). Source: Veterans Affairs Canada (2024).

The vertebral column is divided into five sections: cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral and coccygeal. The lumbar region, often called the “low back”, is composed of five lumbar vertebrae referred to as L1 through L5.

The vertebral bodies change shape and size down the vertebral column, but most share a basic structure. Attached to the body is the neural arch which is a semicircle of bone extending posteriorly from the vertebral body. This arch has a large central opening, or canal. This spinal canal is the opening through which the spinal cord passes as it travels from the brain down the spine. On each side of the neural arch is a notch, the neural foramina where a spinal nerve on each side travel from the spinal cord out through the neural foramina and into the body.

On each side of the neural arch is a small synovial joint called the facet joint. The facet joints guide and limit the movement of a vertebra while also resisting rotation and protecting the neighboring vertebrae from strain.

Intervertebral discs

The intervertebral discs lay between the bodies of adjacent vertebrae above and below. These discs serve as cushions between the vertebrae. The discs consist of a tough outer fibrous ring, which surrounds a soft, gel-like center. The area where the disc attaches to the bony vertebra is the vertebral end plate. Intervertebral discs are typically named for the vertebra above and the vertebra below. For example, the intervertebral disc between the third lumbar vertebrae, L3, and the fourth lumbar vertebra, L4, is called the L3-L4 disc.

Nerve tissue of the lumbar spinal region

The spinal cord is a large bundle of nerves carrying information between the brain and the rest of the body providing sensation to the skin, controlling muscle movement, and regulating the function of body organs, such as the heart or bladder. The spinal cord continues down the spinal column to the level of the first or second lumbar vertebrae. The spinal cord usually ends at the level of the disc between L1 and L2. Below the spinal cord, the spinal nerves travel through the spinal canal and exit at the lumbar vertebrae. The appearance of the spinal nerves in the spinal canal of the lumbar region is named the cauda equina.

Information is carried between the brain and body, and leaves the spinal cord via the spinal nerves. Two spinal nerves exit, one right and one left, below each vertebra. The lumbar spinal nerves are designated by the vertebra above. For example, the spinal nerve which exists below the first lumbar vertebrae, L1, is termed the L1 spinal nerve. The part of the nerve exiting the spinal canal is the spinal nerve root. The spinal nerves are delicate structures and can be injured from compression or stretching.

Spinal nerves travel to specific destinations. The area of skin innervated by a single spinal nerve is a dermatome. The muscle, or group of muscles, innervated by a single spinal nerve is a myotome. For example, the spinal nerve which exits below the right side of the fourth lumbar vertebra, spinal nerve L4, travels to the muscles which straighten the right knee and to the skin to provide sensation to the middle of the right lower leg. The L4 spinal nerve on the left side serves the same areas on the left side of the body.

OA is caused by the breakdown of cartilage in joints and can occur in almost any joint in the body. When OA affects the spine, it is known as spondylosis. Spondylosis is a degenerative disorder that can cause loss of normal spinal structure and function. Lumbar OA (spondylosis) can involve the intervertebral discs and facet joints, leading to disc degeneration and bone spurs (osteophytes) which can pinch the nerves near the discs or spurs.

As spondylosis worsens, progressive narrowing caused by osteophytes can limit the spaces in the spine pressuring the spinal cord and/or nerve roots (spinal stenosis). This compression can impair function and cause pain and/or numbness.

The slippage of one vertebra over another is called degenerative spondylolisthesis and is caused by OA of the facet joints.

Degenerative conditions of the lumbar spine

Clinical features of degenerative conditions of the lumbar spine

In the earliest stage of lumbar disc degeneration, cracks develop in the outer circumferential portion of the disc (annulus fibrosus). The cracks extend from the nucleus pulposus (Figure 1: Human vertebrae anatomy) and travel into, but not completely through, the annulus fibrosus. This is known as an internal disc disruption and can cause back pain. The pain is usually chronic and can radiate to the buttocks and posterior thigh. Positions and activities that increase the pressure in the disc, such as sitting or flexion of the spine, can increase the symptoms.

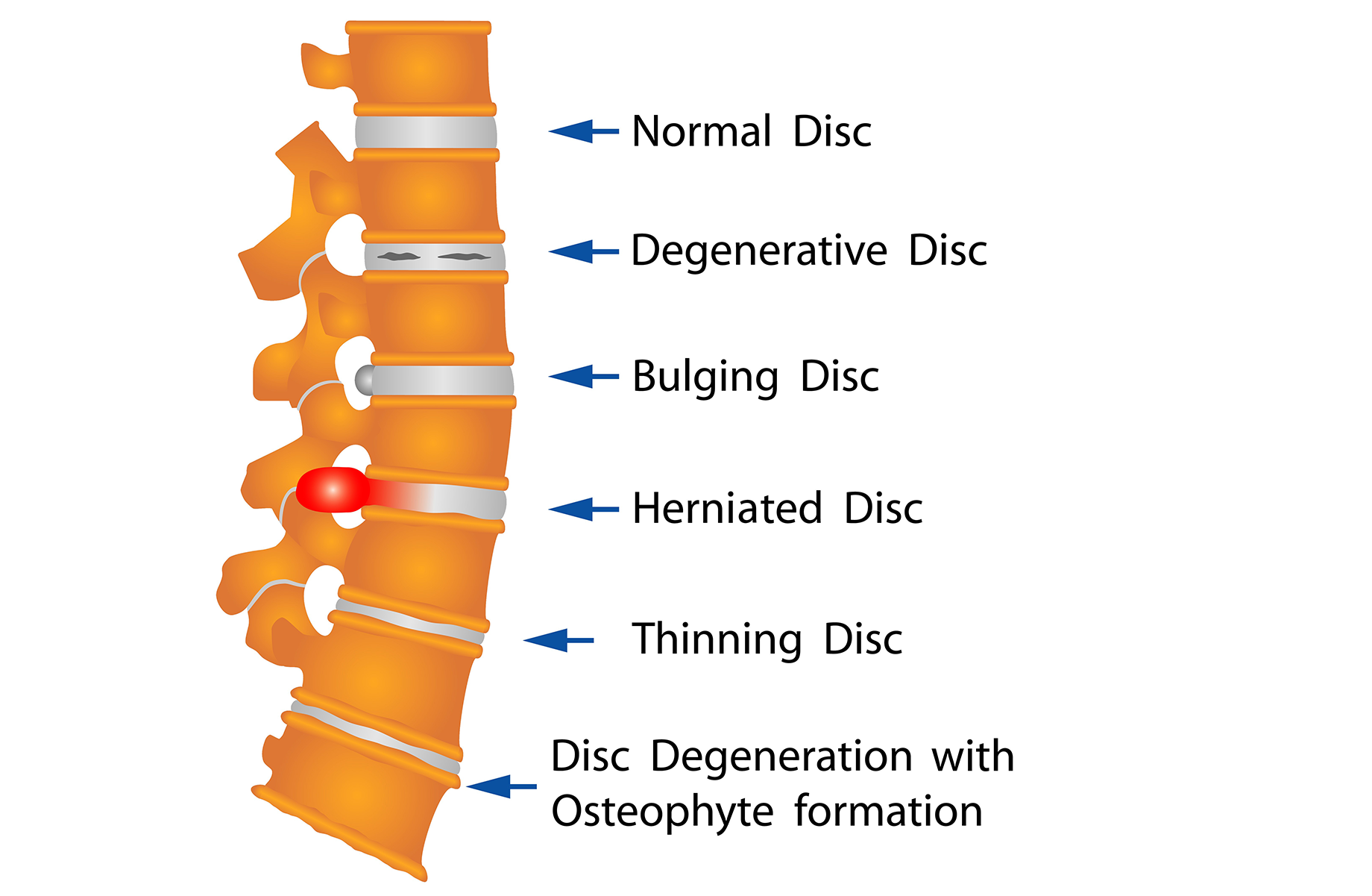

Relatively minor trauma can lead to a complete tear of the annulus fibrosus and herniation of the disc (Figure 2: Lumbar disc degeneration). In many cases, there is no history of clinically significant trauma preceding the onset of disc herniation.

Figure 2: Lumbar disc degeneration

Close-up of the lumbar spine showing the five most common disc issues: a degenerative disc with surface cracks; a bulging disc with outward protrusion; a herniated disc pressing toward the spinal canal; a thinning disc with eroded outer layers; and disc degeneration with osteophyte (bone spur) formation. Source: Veterans Affairs Canada (2024).

In later stages of disc degeneration, the crack(s) can go completely through the annulus fibrosus. The nucleus pulposus may herniate through the crack(s). This is referred to as a herniated or ruptured disc. A herniated disc can cause pain by pressing on the nearby soft tissues or nerves. The resulting symptoms from the compressed spinal nerve are called radiculopathy.

A herniated disc can also intrude into the spinal canal and compress the end of the spinal cord, the conus medullaris in the upper lumbar region or the cauda equina in the lower lumbar region. More than 95% of disc herniations of the lumbar spine occur at the L4-L5 or L5-S1 level.

The signs and symptoms of radiculopathy can include:

- sensory change, such as tingling, known as paresthesia, to the skin in the dermatome (the area of skin innervated by the nerve)

- sensory loss, to the skin in the dermatome

- weakness in the myotome (the muscles innervated by the spinal nerve)

- diminished, or absent, reflex which is controlled by the spinal nerve

- pain felt along the path of the spinal nerve (radicular pain).

OA is a degenerative joint disease of the synovial joints. The facet joints of the lumbar spine are synovial joints and are a common site for the development of OA. Facet joint OA most commonly affects the facet joints of the fourth lumbar vertebra (L4) and the fifth lumbar vertebra (L5).

Osteophytes, commonly referred to as bone spurs, can develop when joints attempt to repair and remodel after injuries and overloading. The osteophytes contribute to enlarged joints and can crowd nearby structures. The enlargement of the joint and presence of osteophytes can cause narrowing of the neural foramina and compression of the spinal nerve root.

There is a range of symptoms with spinal OA, including low back stiffness, pain in the hip, buttocks, or groin. Cramping leg pain typically ending above the knee may be present. The pain may be worse after waking or after periods of inactivity. Pain may be increased with extension of the spine and be relieved by flexion of the spine or lying down.

If the enlarged joints result in spinal nerve root compression, the relevant symptoms of radiculopathy may be present. In the lumbar region, spinal stenosis can compress the end of the spinal cord, the conus medullaris, or the cauda equina. Spinal stenosis (a narrowing of the spinal canal) most commonly affects the L4-L5 level and can occur from ruptured intervertebral discs, enlarged facet joints, osteophytes and/or enlarged ligaments crowding the bony spinal canal.

Spinal stenosis can be congenital or acquired. Congenital spinal stenosis is present at birth as a normal variant in the population or due to a congenital condition. Acquired spinal stenosis is caused by OA of the lumbar spine, which can also be referred to as lumbar spondylosis.

The most common symptom of spinal stenosis is low back pain radiating down both legs below the knees. Typically, the pain is described as a heaviness, weakness, cramping, burning, or numbness in both legs. Symptoms may be more severe in one leg but typically both legs are affected. Symptoms can also worsen with standing for a prolonged time or extension of the lumbar spine. The symptoms can be improved by bending forward, sitting, or resting.

Female biological sex, non-commissioned personnel, and age have been identified as significant risk factors of the development of lumbar disc disease within the Veteran population. Increased risk has also been identified in military helicopter pilots. Incidence of OA of the lumbar spine is higher in female military members, non-commissioned members, and those members serving in the army. Rates of OA of the lumbar spine have been found to be higher among service members in armour/motor transport and in health care compared to other military occupation groups.

Entitlement considerations for degenerative conditions of the lumbar spine

Section A: Causes and/or aggravation of degenerative conditions of the lumbar spine

For Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC) entitlement purposes, the following factors are accepted to cause or aggravate the degenerative conditions of the lumbar spine, and may be considered along with the evidence to assist in establishing a relationship to service. The factors have been determined based on a review of up-to-date scientific and medical literature, as well as evidence-based medical best practices. Factors other than those listed may be considered, however consultation with a disability consultant or medical advisor is recommended.

The timelines cited below are for guidance purposes. Each case should be adjudicated on the evidence provided and its own merits.

Factors for degenerative conditions of the lumbar spine

- Having experienced trauma to the lumbar spine at least six months before, and within 20 years of the clinical onset or aggravation of degenerative conditions of the lumbar spine at the level of, or adjacent to, the area of injury.

- Having a service period lasting 10 full time equivalent (FTE) years or more involving rigorous service activities, tactical training, and maintenance of physical fitness, where the clinical onset or aggravation of degenerative conditions of the lumbar spine has occurred within 25 years of release from service.

Note: VAC accepts the development of the degenerative conditions of the lumbar spine having a service period of at least five FTE years for:

- an anatomically abnormal lumbar spine; or

- female biological sex; or

- evidence of lumbar spine symptoms documented during service.

An anatomically abnormal lumbar spine means a lumbar spine that is affected by underlying muscle weakness or imbalances, neurologic abnormalities, or anatomic variations such as spondylolisthesis of the lumbar spine.

In the case of gender affirming care, consultation with a disability consultant and/or a medical advisor is recommended.

- Having a non-viral infection of the lumbar disc or joint at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of degenerative conditions of the lumbar spine.

- Having one of the following preexisting conditions for at least six months before the clinical onset or aggravation of degenerative conditions of the lumbar spine:

- inflammatory joint disease

- ankylosing spondylitis

- arthritis associated with inflammatory bowel disease

- psoriatic arthritis

- reactive arthritis

- rheumatoid arthritis

- joint deformity

- deformity of a joint of a vertebra

- deformity of a vertebra

- scoliosis

- spondylolisthesis

- spinal fusion immediately above, or below, the affected joint

- uncorrected permanent leg length Inequality (LLI), as outlined in the LLI Discussion Paper.

- inflammatory joint disease

- Inability to obtain appropriate clinical management for degenerative conditions of the lumbar spine.

Section B: Medical conditions which are to be included in entitlement/assessment of degenerative conditions of the lumbar spine

Section B provides a list of diagnosed medical conditions which are considered for VAC purposes to be included in the entitlement and assessment of degenerative conditions of the lumbar spine.

- Lumbar disc disease

- Degenerative disc disease of the lumbar spine

- Intervertebral disc prolapse of the lumbar spine

- Intervertebral disc herniation of the lumbar spine

- Osteoarthritis of the lumbar spine

- Osteoarthritis of the facet joints of the lumbar spine

- Lumbar facet syndrome

- Lumbar spondylosis

- Lumbar spinal stenosis

- Lumbar spondylolysis

- Lumbar spondylolisthesis

- Chronic mechanical low back pain

- Chronic lumbar sprain

- Chronic lumbar strain

- Chronic myofascial pain of the lumbar region

- Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) of the lumbar spine

- Piriformis syndrome

Section C: Common medical conditions which may result, in whole or in part, from degenerative conditions of the lumbar spine and/or their treatment

Section C is a list of conditions which can be caused or aggravated by degenerative conditions of the lumbar spine and/or their treatment. Conditions listed in Section C are not included in the entitlement and assessment of degenerative conditions of the lumbar spine. A consequential entitlement decision may be considered where the individual merits and the medical evidence of the case support a consequential relationship.

Conditions other than those listed in Section C may be considered; consultation with a disability consultant or medical advisor is recommended.

- Cauda equina syndrome

Soft tissue conditions of the lumbar spine

For the purposes of this EEG, the following conditions are included:

- chronic mechanical lumbar back pain

- chronic mechanical low back pain

- chronic lumbar sprain

- chronic lumbar strain

- chronic myofascial pain of the lumbar region.

Clinical features of soft tissue conditions of the lumbar spine

The majority of low back pain is categorized as non-specific low back pain. This is because the structural causes of pain are difficult to identify and characterize. Non-specific low back pain means the pain or discomfort persists in the absence of an underlying condition that can be reliably identified. Soft tissue causes, also known as musculoligamentous causes, contribute to non-specific chronic low back pain.

Chronic lumbar sprain is the stretching or tearing of a low back ligament(s). Chronic lumbar strain is the stretching or tearing of a low back muscle(s) and/or tendon(s). Both chronic lumbar sprain and strain present with identical signs and symptoms, including discomfort, pain, tenderness, tightness, or stiffness of the lumbar area and/or decreased range of motion of the lumbar spine.

Chronic myofascial pain of the lumbar region may present with the same signs and symptoms as chronic lumbar sprains and strains and/or with typical patterns of radiating pain from trigger points. Trigger points are sensitive areas in muscles or fasciae that become painful when compressed.

Chronic mechanical lumbar back pain and chronic mechanical low back pain include pain originating from the structural elements of the lumbar spine. These structural elements being the vertebrae, joints of the spinal column, intervertebral discs, ligaments, muscles, and/or tendons.

The clinical features of chronic mechanical lumbar back pain and chronic mechanical low back pain are dependent on the structure(s) affected by an injury and/or a disease process. This can lead to a variety of clinical presentations.

Chronic mechanical lumbar back pain and chronic mechanical low back pain, which primarily affect the soft tissues of the low back, will have signs and symptoms similar to lumbar sprain, lumbar strain, or myofascial pain of the lumbar region.

Chronic mechanical lumbar back pain and chronic mechanical low back pain which affect the structural elements of the back will have signs and symptoms similar to lumbar spondylosis.

Risk factors for soft tissue conditions in military personnel include g-force exposure in pilots and aircrew, extreme shock and vibration exposure, heavy combat load requirements, and falls incurred during airborne, air assault, and urban dismounted ground operations. Female biological sex and non-commissioned members are also risk factors for low back pain.

Entitlement considerations for soft tissue conditions of the lumbar spine

Section A: Causes and/or aggravation of soft tissue conditions of the lumbar spine

For VAC entitlement purposes, the following factors are accepted to cause or aggravate the soft tissue conditions of the lumbar spine, and may be considered along with the evidence to assist in establishing a relationship to service. The factors have been determined based on a review of up-to-date scientific and medical literature, as well as evidence-based medical best practices. Factors other than those listed may be considered, however consultation with a disability consultant or medical advisor is recommended.

The timelines cited below are for guidance purposes. Each case should be adjudicated on the evidence provided and its own merits.

Factors for soft tissue conditions of the lumbar spine

- Experiencing a physical force applied to or through the affected lumbar spine joint, at the time of the clinical onset or aggravation of the soft tissue condition of the lumbar spine.

- Experiencing forceful stretching or overuse of a muscle or tendon in the lumbar spine at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of soft tissue conditions of the lumbar spine.

- Having uncorrected leg length inequality (LLI) with a LLI of 1.5 cm or greater at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of soft tissue conditions of the lumbar spine where LLI is present for several months prior to development of the condition.

- Inability to obtain appropriate clinical management for soft tissue conditions of the lumbar spine.

Section B: Medical conditions which are to be included in the entitlement/assessment of soft tissue conditions of the lumbar spine

Section B provides a list of diagnosed medical conditions which are considered for VAC purposes to be included in the entitlement and assessment of soft tissue conditions of the lumbar spine.

- Lumbar disc disease

- Degenerative disc disease of the lumbar spine

- Intervertebral disc prolapse of the lumbar spine

- Intervertebral disc herniation of the lumbar spine

- Osteoarthritis of the lumbar spine

- Osteoarthritis of the facet joints of the lumbar spine

- Lumbar facet syndrome

- Lumbar spondylosis

- Lumbar spinal stenosis

- Lumbar spondylolysis

- Lumbar spondylolisthesis

- Chronic mechanical lumbar back pain

- Chronic mechanical low back pain

- Chronic lumbar sprain

- Chronic lumbar strain

- Chronic myofascial pain of the lumbar region

- Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) of the lumbar spine

- Piriformis syndrome

Section C: Common medical conditions which may result, in whole or in part, from soft tissue conditions of the lumbar spine and/or their treatment

No consequential medical conditions were identified at the time of the publication of this EEG. If the merits of the case and medical evidence indicate that a possible consequential relationship may exist, consultation with a disability consultant or medical advisor is recommended.

Links

Related VAC guidance and policy:

- Ankylosing Spondylitis – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Leg Length Inequality (LLI) – Discussion Paper

- Rheumatoid Arthritis – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Spondylolisthesis and Spondylolysis – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Pain and Suffering Compensation - Policies

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police Disability Pension Claims - Policies

- Dual Entitlement – Disability Benefits - Policies

- Establishing the Existence of a Disability - Policies

- Disability Benefits in Respect of Peacetime Military Service – The Compensation Principle - Policies

- Disability Benefits in Respect of Wartime and Special Duty Service – The Insurance Principle - Policies

- Disability Resulting from a Non-Service Related Injury or Disease - Policies

- Consequential Disability - Policies

- Benefit of Doubt - Policies

References as of 31 March 2025

Al-Otaibi, S. (2015). Prevention of occupational Back Pain. Journal of Family and Community Medicine, 22(2), 73. https://doi.org/10.4103/2230-8229.155370

Adogwa, O., Davison, M. A., Vuong, V., Desai, S. A., Lilly, D. T., Moreno, J., Cheng, J., & Bagley, C. (2019). Sex Differences in Opioid Use in Patients With Symptomatic Lumbar Stenosis or Spondylolisthesis Undergoing Lumbar Decompression and Fusion. Spine, 44(13), E800–E807. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000002965

Akkawi, I., & Zmerly, H. (2022). Degenerative Spondylolisthesis: A Narrative Review. Acta Bio Medica: Atenei Parmensis, 92(6), e2021313. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v92i6.10526

Alshami, A. M. (2015). Prevalence of spinal disorders and their relationships with age and gender. Saudi Medical Journal, 36(6), 725–730. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2015.6.11095

Anderson, A. B., Braswell, M. J., Pisano, A. J., Watson, N. I., Dickens, J. F., Helgeson, M. D., Brooks, D. I., & Wagner, S. C. (2021). Factors Associated With Progression to Surgical Intervention for Lumbar Disc Herniation in the Military Health System. Spine, 46(6), E392–E397.https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000003815

Anderson, A. B., Watson, N. L., Pisano, A. J., Neal, C. J., Fredricks, D. J., Helgeson, M. D., Brooks, D. I., & Wagner, S. C. (2023). Rates and Predictors of Surgery for Lumbar Disc Herniation Between the Military and Civilian Health Care Systems. Military Medicine, 188(7–8), e1842–e1846. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usad004

Anderson, J. T., Haas, A. R., Percy, R., Woods, S. T., Ahn, U. M., & Ahn, N. U. (2016). Workers’ Compensation, Return to Work, and Lumbar Fusion for Spondylolisthesis. Orthopedics, 39(1). https://doi.org/10.3928/01477447-20151218-01

Annongu, T., Chia, M., Aligba, T., & Magaji, O. (2023). Correlation of Severe Lumbar Spondylosis with Socio-Demographics of Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain. International Journal of Scientific Research in Dental and Medical Sciences, Online First. https://doi.org/10.30485/ijsrdms.2023.399554.1498

Australian Government Repatriation Medical Authority (2018). Amendment Statement of Principles concerning lumbar spondylosis (No. 68 of 2018). SOPs - Repatriation Medical Authority

Australian Government Repatriation Medical Authority (2018). Amendment Statement of Principles concerning lumbar spondylosis (No. 67 of 2018). SOPs - Repatriation Medical Authority

Australian Government Repatriation Medical Authority (2023). Statement of Principles concerning thoracolumbar intervertebral disc prolapse (Balance of Probabilities) (No. 69 of 2023). SOPs - Repatriation Medical Authority

Australian Government Repatriation Medical Authority (2023). Statement of Principles concerning thoracolumbar intervertebral disc prolapse (Reasonable Hypothesis) (No. 68 of 2023). SOPs - Repatriation Medical Authority

Brinckmann, P., Frobin, W., Biggemann, M., Tillotson, M., Burton, K., Burke, C., Dickinson, C., Krause, H., Pangert, R., Pfeifer, U., Römer, H., Rysanek, M., Weiß, D., Wilson, T., Zarach, V., & Zerlett, G. (1998). Quantification of overload injuries to thoracolumbar vertebrae and discs in persons exposed to heavy physical exertions or vibration at the workplace Part II Occurrence and magnitude of overload injury in exposed cohorts. Clinical Biomechanics, 13, S1–S36. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0268-0033(98)00050-3

Burström, L., Nilsson, T., & Wahlström, J. (2015). Whole-body vibration and the risk of low back pain and sciatica: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 88(4), 403–418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-014-0971-4

Buruck, G., Tomaschek, A., Wendsche, J., Ochsmann, E., & Dörfel, D. (2019). Psychosocial areas of worklife and chronic low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 20(1), 480. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-019-2826-3

Canale, S. T., & Campbell, W. C. (Eds.). (1998). Campbell’s operative orthopaedics (9th ed). Mosby.

Cannata, F., Vadalà, G., Ambrosio, L., Fallucca, S., Napoli, N., Papalia, R., Pozzilli, P., & Denaro, V. (2020). Intervertebral disc degeneration: A focus on obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews, 36(1), e3224. https://doi.org/10.1002/dmrr.3224

Cardoso, E. S., Fernandes, S. G. G., Corrêa, L. C. de A. C., Dantas, G. A. de F., & Câmara, S. M. A. da. (2018). Low back pain and disability in military police: An epidemiological study. Fisioterapia Em Movimento, 31(0). https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-5918.031.ao01

Celtikci, E., Yakar, F., Celtikci, P., & Izci, Y. (2018). Relationship between individual payload weight and spondylolysis incidence in Turkish land forces. Neurosurgical Focus, 45(6), E12. https://doi.org/10.3171/2018.8.FOCUS18375

Chan, A. K., Bisson, E. F., Fu, K.-M., Park, P., Robinson, L. C., Bydon, M., Glassman, S. D., Foley, K. T., Shaffrey, C. I., Potts, E. A., Shaffrey, M. E., Coric, D., Knightly, J. J., Wang, M. Y., Slotkin, J. R., Asher, A. L., Virk, M. S., Kerezoudis, P., Alvi, M. A., … Mummaneni, P. V. (2020). Sexual Dysfunction: Prevalence and Prognosis in Patients Operated for Degenerative Lumbar Spondylolisthesis. Neurosurgery, 87(2), 200–210. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuros/nyz406

Coenen, P., Gouttebarge, V., van der Burght, A. S. A. M., van Dieën, J. H., Frings-Dresen, M. H. W., van der Beek, A. J., & Burdorf, A. (2014). The effect of lifting during work on low back pain: A health impact assessment based on a meta-analysis. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 71(12), 871–877. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2014-102346

Cohen, S. P., Gallagher, R. M., Davis, S. A., Griffith, S. R., & Carragee, E. J. (2012). Spine-area pain in military personnel: A review of epidemiology, etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. The Spine Journal, 12(9), 833–842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2011.10.010

Dario, A. B., Ferreira, M. L., Refshauge, K. M., Lima, T. S., Ordoñana, J. R., & Ferreira, P. H. (2015). The relationship between obesity, low back pain, and lumbar disc degeneration when genetics and the environment are considered: A systematic review of twin studies. The Spine Journal, 15(5), 1106–1117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2015.02.001

Davison, M. A., Vuong, V. D., Lilly, D. T., Desai, S. A., Moreno, J., Cheng, J., Bagley, C., & Adogwa, O. (2018). Gender Differences in Use of Prolonged Nonoperative Therapies Before Index Lumbar Surgery. World Neurosurgery, 120, e580–e592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2018.08.131

Dee, R. (Ed.). (1997). Principles of orthopaedic practice (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill, Health Professions Division.

DK, K., YS, D., B, B., & I, V. (n.d.). A Retrospective Analysis of Low Backache with Associated Lumbo-Sacral Disabilities in Military Aviators. Indian Journal of Aerospace Medicine, 59.

Edwards, C. M., da Silva, D. F., Souza, S. C. S., Puranda, J. L., Nagpal, T. S., Semeniuk, kevin, & Adamo, K. B. (2022). Body Regions Susceptible To Musculoskeletal Injuries In Canadian Armed Forces Pilots: 549. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 54(9S), 139–139. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.mss.0000876780.96756.37

Fraser, R. D., Brooks, F., & Dalzell, K. (2019). Degenerative spondylolisthesis: A prospective cross-sectional cohort study on the role of weakened anterior abdominal musculature on causation. European Spine Journal, 28, 1406-1412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-018-5758-y

Furlan, J. C., Gulasingam, S., & Craven, B. C. (2019). Epidemiology of War-Related Spinal Cord Injury Among Combatants: A Systematic Review. Global Spine Journal, 9(5), 545–558. https://doi.org/10.1177/2192568218776914

Garcia, A., Kretzmer, T. S., Dams-O’Connor, K., Miles, S. R., Bajor, L., Tang, X., Belanger, H. G., Merritt, B. P., Eapen, B., McKenzie-Hartman, T., & Silva, M. A. (2022). Health Conditions Among Special Operations Forces Versus Conventional Military Service Members: A VA TBI Model Systems Study. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 37(4), E292–E298. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0000000000000737

Girzelska, J., & Chomicki, L. (2021). The relationship between the experience of negative feelings and quality of life and the socio-demographical factors of patients treated for discopathy of the lumbar spine. Acta Neurophychologica, 19(1), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0014.7570

Gandhi, R., Woo, K. M., Zywiel, M. G., & Rampersaud, Y. R. (2014). Metabolic Syndrome Increases the Prevalence of Spine Osteoarthritis. Orthopaedic Surgery, 6(1), 23–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/os.12093

Gomes, S. R. A., Mendes, P. R. F., Costa, L. D. O., Bulhões, L. C. C., Borges, D. T., Macedo, L. B., & Brasileiro, J. (2022). Factors associated with low back pain in air force fighter pilots: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Military Health, 168(4), 299–302. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjmilitary-2021-001851

Goode, A. P., Cleveland, R. J., George, S. Z., Kraus, V. B., Schwartz, T. A., Gracely, R. H., Jordan, J. M., & Golightly, Y. M. (2020). Different Phenotypes of Osteoarthritis in the Lumbar Spine Reflected by Demographic and Clinical Characteristics: The Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Arthritis Care & Research, 72(7), 974–981. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23918

Goode, A. P., Cleveland, R. J., George, S. Z., Schwartz, T. A., Kraus, V. B., Renner, J. B., Gracely, R. H., DeFrate, L. E., Hu, D., Jordan, J. M., & Golightly, Y. M. (2022). Predictors of Lumbar Spine Degeneration and Low Back Pain in the Community: The Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Arthritis Care & Research, 74(10), 1659–1666. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.24643

Granado, N. S., Pietrucha, A., Ryan, M., Boyko, E. J., Hooper, T. I., Smith, B., & Smith, T. C. (2016). Longitudinal Assessment of Self-Reported Recent Back Pain and Combat Deployment in the Millennium Cohort Study. Spine, 41(22), 1754–1763. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000001739

Griffith, L. E., Shannon, H. S., Wells, R. P., Walter, S. D., Cole, D. C., Côté, P., Frank, J., Hogg-Johnson, S., & Langlois, L. E. (2012). Individual Participant Data Meta-Analysis of Mechanical Workplace Risk Factors and Low Back Pain. American Journal of Public Health, 102(2), 309–318. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300343

Harper, J., O’Donnell, E., Khorashad, B. S., McDermott, H., & Witcomb, G. L. (2021). How does hormone transition in transgender women change body composition, muscle strength and haemoglobin? Systematic review with a focus on the implications for sport participation. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 55(15), 865–872. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-103106

Jaffar, N. A. T., & Rahman, M. N. A. (2017). Review on risk factors related to lower back disorders at workplace. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 226, 012035. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/226/1/012035

Jahn, A., Andersen, J. H., Christiansen, D. H., Seidler, A., & Dalbøge, A. (2023). Association between occupational exposures and chronic low back pain: Protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE, 18(5), e0285327. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285327

Jia, N., Zhang, M., Zhang, H., Ling, R., Liu, Y., Li, G., Yin, Y., Shao, H., Zhang, H., Qiu, B., Li, D., Wang, D., Zeng, Q., Wang, R., Chen, J., Zhang, D., Mei, L., Fang, X., Liu, Y., … Wang, Z. (2022). Prevalence and risk factors analysis for low back pain among occupational groups in key industries of China. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1493. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13730-8

Kang, S. H., Yang, J. S., Cho, Y. J., Park, S. W., & Ko, K. P. (2014). Military Rank and the Symptoms of Lumbar Disc Herniation in Young Korean Soldiers. World Neurosurgery, 82(1–2), e9–e14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2013.02.056

Knox, J. B., Deal, J. B., & Knox, J. A. (2018). Lumbar Disc Herniation in Military Helicopter Pilots vs. Matched Controls. Aerospace Medicine and Human Performance, 89(5), 442–445. https://doi.org/10.3357/AMHP.4935.2018

Knox, J., Orchowski, J., Scher, D. L., Owens, B. D., Burks, R., & Belmont, P. J. (2011). The Incidence of Low Back Pain in Active Duty United States Military Service Members: Spine, 36(18), 1492–1500. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181f40ddd

Koreerat, N. R., & Koreerat, C. M. (2021). Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Injuries in a Security Force Assistance Brigade Before, During, and After Deployment. Military Medicine, 186(Supplement_1), 704–708. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usaa334

Kuijer, P. P. F. M., Verbeek, J. H., Seidler, A., Ellegast, R., Hulshof, C. T. J., Frings-Dresen, M. H. W., & Van der Molen, H. F. (2018). Work-relatedness of lumbosacral radiculopathy syndrome: Review and dose-response meta-analysis. Neurology, 91(12), 558–564. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000544322.26939.09

Kuperus, J. S., Mohamed Hoesein, F. A. A., de Jong, P. A., & Verlaan, J. J. (2020). Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis: Etiology and clinical relevance. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology, 34(3), 101527.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2020.101527

Lener, S., Wipplinger, C., Hartmann, S., Thomé, C., & Tschugg, A. (2020). The impact of obesity and smoking on young individuals suffering from lumbar disc herniation: A retrospective analysis of 97 cases. Neurosurgical Review, 43(5), 1297–1303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-019-01151-y

Levin, K. (2019). Lumbar spinal stenosis: pathophysiology, clinical features, and diagnosis. UpToDate.

Lindsey, T., & Dydyk, A. M. (2024). Spinal Osteoarthritis. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553190/

Macedo, L. G., & Battié, M. C. (2019). The association between occupational loading and spine degeneration on imaging – a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 20(1), 489. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-019-2835-2

Marshall, L. W., & McGill, S. M. (2010). The role of axial torque in disc herniation. Clinical Biomechanics, 25(1), 6–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2009.09.003

Mastalerz, A., Maruszyńska, I., Kowalczuk, K., Garbacz, A., & Maculewicz, E. (2022). Pain in the Cervical and Lumbar Spine as a Result of High G-Force Values in Military Pilots—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13413. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013413

Mateos-Valenzuela, A. G., González-Macías, M. E., Ahumada-Valdez, S., Villa-Angulo, C., & Villa-Angulo, R. (2020). Risk factors and association of body composition components for lumbar disc herniation in Northwest, Mexico. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 18479. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75540-5

Monnier, A., Djupsjöbacka, M., Larsson, H., Norman, K., & Äng, B. O. (2016). Risk factors for back pain in marines; a prospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 17(1), 319. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-016-1172-y

Muraki, S., Akune, T., Oka, H., Mabuchi, A., En‐Yo, Y., Yoshida, M., Saika, A., Nakamura, K., Kawaguchi, H., & Yoshimura, N. (2009). Association of occupational activity with radiographic knee osteoarthritis and lumbar spondylosis in elderly patients of population‐based cohorts: A large‐scale population‐based study. Arthritis Care & Research, 61(6), 779–786. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.24514

Murray, K. J., Le Grande, M. R., Ortega de Mues, A., & Azari, M. F. (2017). Characterisation of the correlation between standing lordosis and degenerative joint disease in the lower lumbar spine in women and men: A radiographic study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 18(1), 330. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-017-1696-9

Nissen, L. R., Marott, J. L., Gyntelberg, F., & Guldager, B. (2014). Deployment-Related Risk Factors of Low Back Pain: A Study Among Danish Soldiers Deployed to Iraq. Military Medicine, 179(4), 451–458. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00317

Onodera, K., Berry, D. B., Shahidi, B., Kelly, K. R., & Ward, S. R. (2019). Intervertebral disc kinematics in active duty Marines with and without lumbar spine pathology. JOR SPINE, 2(2). https://doi.org/10.1002/jsp2.1057

Orsello, C. A., Phillips, A. S., & Rice, G. M. (2013). Height and In-Flight Low Back Pain Association Among Military Helicopter Pilots. Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine, 84(1), 32–37. https://doi.org/10.3357/ASEM.3425.2013

Palmer, K. T., Griffin, M., Ntani, G., Shambrook, J., McNee, P., Sampson, M., Harris, E. C., & Coggon, D. (2012). Professional driving and prolapsed lumbar intervertebral disc diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging: A case–control study. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 38(6), 577–581. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3273

Papaioannou, M., Skapinakis, P., Damigos, D., Mavreas, V., Broumas, G., & Palgimesi, A. (2009). The Role of Catastrophizing in the Prediction of Postoperative Pain. Pain Medicine, 10(8), 1452–1459. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00730.x

Parkinson, R. J., & Callaghan, J. P. (2009). The role of dynamic flexion in spine injury is altered by increasing dynamic load magnitude. Clinical Biomechanics, 24(2), 148–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2008.11.007

Peteler, R., Schmitz, P., Loher, M., Jansen, P., Grifka, J., & Benditz, A. (2021). Sex-Dependent Differences in Symptom-Related Disability Due to Lumbar Spinal Stenosis. Journal of Pain Research, Volume 14, 747–755. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S294524

Peul, W. C., Brand, R., Thomeer, R. T. W. M., & Koes, B. W. (2008). Influence of gender and other prognostic factors on outcome of sciatica. Pain, 138(1), 180–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2007.12.014

Rhon, D. I., Teyhen, D. S., Kiesel, K., Shaffer, S. W., Goffar, S. L., Greenlee, T. A., & Plisky, P. J. (2022). Recovery, Rehabilitation, and Return to Full Duty in a Military Population After a Recent Injury: Differences Between Lower-Extremity and Spine Injuries. Arthroscopy, Sports Medicine, and Rehabilitation, 4(1), e17–e27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asmr.2021.09.028

Robinson, W. A., Hevesi, M., Carlson, B. C., Schulte, S., Petfield, J. L., & Freedman, B. A. (2019). Spinal Fusions in Active Military Personnel: Who Gets a Lumbar Spinal Fusion in the Military and What Impact Does It Have on Service Member Retention? Military Medicine, 184(1–2), e156–e161. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usy139

Roffey, D. M., Wai, E. K., Bishop, P., Kwon, B. K., & Dagenais, S. (2010). Causal assessment of occupational sitting and low back pain: Results of a systematic review. The Spine Journal, 10(3), 252–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2009.12.005

Schoenfeld, A. J. (2011). Low Back Pain in the Uniformed Service Member: Approach to Surgical Treatment Based on a Review of the Literature. Military Medicine, 176(5), 544–551. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-10-00397

Schoenfeld, A. J., Nelson, J. H., Burks, R., & Belmont, P. J. (2011). Incidence and Risk Factors for Lumbar Degenerative Disc Disease in the United States Military 1999–2008. Military Medicine, 176(11), 1320–1324. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-11-00061

Schröder, C., & Nienhaus, A. (2020). Intervertebral Disc Disease of the Lumbar Spine in Health Personnel with Occupational Exposure to Patient Handling—A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(13), 4832. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134832

Schroeder, G. D., Guyre, C. A., & Vaccaro, A. R. (2016). The epidemiology and pathophysiology of lumbar disc herniations. Seminars in Spine Surgery, 28(1), 2–7. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semss.2015.08.003

Seidler, A. (2001). The role of cumulative physical work load in lumbar spine disease: Risk factors for lumbar osteochondrosis and spondylosis associated with chronic complaints. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 58(11), 735–746. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.58.11.735

Seidler, A. (2003). Occupational risk factors for symptomatic lumbar disc herniation; a case-control study. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 60(11), 821–830. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.60.11.821

Seidler, A., Bergmann, A., Jäger, M., Ellegast, R., Ditchen, D., Elsner, G., Grifka, J., Haerting, J., Hofmann, F., Linhardt, O., Luttmann, A., Michaelis, M., Petereit-Haack, G., Schumann, B., & Bolm-Audorff, U. (2009). Cumulative occupational lumbar load and lumbar disc disease – results of a German multi-center case-control study (EPILIFT). BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 10(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-10-48

Shah, J. M., Wahezi, S. E., & Silva, K. (2017). Lumbar Spondylotic and Arthritic Pain. In S. B. Kahn & R. Y. Xu (Eds.), Musculoskeletal Sports and Spine Disorders (pp. 443–446). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-50512-1_98

Shenoy, K., & Kim, Y. H. (2020). The Military Medical System and Wartime Injuries to the Spine. Bulletin of the Hospital for Joint Disease (2013), 78(1), 42–45.

Shiri, R., Frilander, H., Sainio, M., Karvala, K., Sovelius, R., Vehmas, T., & Viikari-Juntura, E. (2015). Cervical and lumbar pain and radiological degeneration among fighter pilots: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 72(2), 145–150. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2014-102268

Shiri, R., Falah‐Hassani, K., Heliövaara, M., Solovieva, S., Amiri, S., Lallukka, T., Burdorf, A., Husgafvel‐Pursiainen, K., & Viikari‐Juntura, E. (2019). Risk Factors for Low Back Pain: A Population‐Based Longitudinal Study. Arthritis Care & Research, 71(2), 290–299. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23710

Simas, V., Canetti, E., Schram, B., Campbell, P. G., Pope, R., & Orr, R. M. (2020). Tactical Research Unit Report for the Department of Veterans’ Affairs: Spondylosis - A Rapid Review.

Sommer, F., Gadjradj, P. S., & Pippig, T. (2023). Spinal injuries after ejection seat evacuation in fighter aircraft of the German Armed Forces between 1975 and 2021. Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine, 38(2), 271–278. https://doi.org/10.3171/2022.8.SPINE22644

Sørensen, I. G., Jacobsen, P., Gyntelberg, F., & Suadicani, P. (2011). Occupational and Other Predictors of Herniated Lumbar Disc Disease—A 33-Year Follow-up in The Copenhagen Male Study: Spine, 36(19), 1541–1546. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181f9b8d4

Stannard, J., & Fortington, L. (2021). Musculoskeletal injury in military Special Operations Forces: A systematic review. BMJ Military Health, 167(4), 255–265. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjmilitary-2020-001692

Steelman, T., Lewandowski, L., Helgeson, M., Wilson, K., Olsen, C., & Gwinn, D. (2018). Population-based Risk Factors for the Development of Degenerative Disk Disease. Clinical Spine Surgery: A Spine Publication, 31(8), E409–E412. https://doi.org/10.1097/BSD.0000000000000682

Swain, C. T. V., Pan, F., Owen, P. J., Schmidt, H., & Belavy, D. L. (2020). No consensus on causality of spine postures or physical exposure and low back pain: A systematic review of systematic reviews. Journal of Biomechanics, 102, 109312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2019.08.006

Taniguchi, Y., Akune, T., Nishida, N., Omori, G., Ha, K., Ueno, K., Saito, T., Oichi, T., Koike, A., Mabuchi, A., Oka, H., Muraki, S., Oshima, Y., Kawaguchi, H., Nakamura, K., Tokunaga, K., Tanaka, S., & Yoshimura, N. (2023). A common variant rs2054564 in ADAMTS17 is associated with susceptibility to lumbar spondylosis. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 4900. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-32155-w

Tegern, M., Aasa, U., Äng, B. O., & Larsson, H. (2020). Musculoskeletal disorders and their associations with health- and work-related factors: A cross-sectional comparison between Swedish air force personnel and army soldiers. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 21(1), 303. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-03251-z

To, D., Rezai, M., Murnaghan, K., & Cancelliere, C. (2021). Risk factors for low back pain in active military personnel: A systematic review. Chiropractic & Manual Therapies, 29(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12998-021-00409-x

Unger, C. A. (2016). Hormone therapy for transgender patients. Translational Andrology and Urology, 5(6), 877–884. https://doi.org/10.21037/tau.2016.09.04

Ulaska, J., Visuri, T., Pulkkinen, P., & Pekkarinen, H. (2001). Impact of Chronic Low Back Pain on Military Service. Military Medicine, 166(7), 607–611. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/166.7.607

Urits, I., Burshtein, A., Sharma, M., Testa, L., Gold, P. A., Orhurhu, V., Viswanath, O., Jones, M. R., Sidransky, M. A., Spektor, B., & Kaye, A. D. (2019). Low Back Pain, a Comprehensive Review: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Current Pain and Headache Reports, 23(3), 23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-019-0757-1

Vähi, I., Rips, L., Varblane, A., & Pääsuke, M. (2023). Musculoskeletal Injury Risk in a Military Cadet Population Participating in an Injury-Prevention Program. Medicina, 59(2), 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59020356

Veterans Affairs Canada (2024). Dermatomes. License purchased for use from https://www.123rf.com/photo_142519115_dermatomes-vector-illustration-labeled-educational-anatomical-skin-parts-scheme-epidermis-area.html

Veterans Affairs Canada (2024). Human Vertebrae Anatomy. License purchased for use from Vertebrae Spinal Cord Anatomy Infographics With Set Of Isolated Scientific Images Human Body Silhouette And Text Vector Illustration Royalty Free SVG, Cliparts, Vectors, and Stock Illustration. Image 200099118. (123rf.com)

Veterans Affairs Canada (2024). Lumbar Disc Degeneration. License purchased for use from Spine Conditions Degenerative Disc Bulging Disc Herniated Disc Thinning Disc Disc Degeneration With Osteophyte Formation Royalty Free SVG, Cliparts, Vectors, and Stock Illustration. Image 27905832. (123rf.com)

Vincent, H. K., Seay, A. N., Montero, C., Conrad, B. P., Hurley, R. W., & Vincent, K. R. (2013). Functional Pain Severity and Mobility in Overweight Older Men and Women with Chronic Low-Back Pain—Part I. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 92(5), 430–438. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0b013e31828763a0

Virta, L. (1992). Prevalence of isthmic lumbar spondylolisthesis in middle-aged subjects from eastern and western Finland. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 45(8), 917–922. https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(92)90075-X

Wang, Y. X. J., Káplár, Z., Deng, M., & Leung, J. C. S. (2017). Lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis epidemiology: A systematic review with a focus on gender-specific and age-specific prevalence. Journal of Orthopaedic Translation, 11, 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jot.2016.11.001

Walsh, G. S., & Harrison, I. (2022). Gait and neuromuscular dynamics during level and uphill walking carrying military loads. European Journal of Sport Science, 22(9), 1364–1373. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2021.1953154

Walsh, G. S., & Low, D. C. (2021). Military load carriage effects on the gait of military personnel: A systematic review. Applied Ergonomics, 93, 103376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2021.103376

Waqqash, E., Hafiz, E., Shariff A Hamid, M., & Md Nadzalan, A. (2018). A Narrative Review: Risk Factors of Low Back Pain in Military Personnel/Recruits. International Journal of Engineering & Technology, 7(4.15), 159. https://doi.org/10.14419/ijet.v7i4.15.21439

Weiner, D. K., Holloway, K., Levin, E., Keyserling, H., Epstein, F., Monaco, E., Sembrano, J., Brega, K., Nortman, S., Krein, S. L., Gentili, A., Katz, J. N., Morrow, L. A., Muluk, V., Pugh, M. J., & Perera, S. (2021). Identifying biopsychosocial factors that impact decompressive laminectomy outcomes in veterans with lumbar spinal stenosis: A prospective cohort study. Pain, 162(3), 835–845. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002072

Wheeler S.G., Wipf, J., Staiger, T., Deyo, R., Jarvik, J. (2022). Evaluation of low back pain in adults. UpToDate.

Williams, V. F., Clark, L. L., & Oh, G.-T. (2016). Update: Osteoarthritis and spondylosis, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2010-2015. MSMR, 23(9), 14–22.

World Health Organization. (2019). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th Revision). https://icd.who.int/

Xu, X., Li, X., & Wu, W. (2015). Association Between Overweight or Obesity and Lumbar Disk Diseases: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Spinal Disorders & Techniques, 28(10), 370–376. https://doi.org/10.1097/BSD.0000000000000235

Yoshihara, H. (2020). Pathomechanisms and Predisposing Factors for Degenerative Lumbar Spondylolisthesis: A Narrative Review. JBJS Reviews, 8(9), e20.00068-e20.00068. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.RVW.20.00068

Zavarize, S. F., & Wechsler, S. M. (2016). Evaluación de las diferencias de género en las estrategias de afrontamiento del dolor lumbar. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 35–56. https://doi.org/10.14718/ACP.2016.19.1.3

Zhang, Y., Sun, Z., Zhang, Z., Liu, J., & Guo, X. (2009). Risk Factors for Lumbar Intervertebral Disc Herniation in Chinese Population: A Case-Control Study. Spine, 34(25), E918–E922. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a3c2de

Zhou, J., Mi, J., Peng, Y., Han, H., & Liu, Z. (2021). Causal Associations of Obesity With the Intervertebral Degeneration, Low Back Pain, and Sciatica: A Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 12, 740200. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2021.740200

Zhu, K., Su, Q., Chen, T., Zhang, J., Yang, M., Pan, J., Wan, W., Zhang, A., & Tan, J. (2020). Association between lumbar disc herniation and facet joint osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 21(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-3070-6

Zielinska, N., Podgórski, M., Haładaj, R., Polguj, M., & Olewnik, Ł. (2021). Risk Factors of Intervertebral Disc Pathology—A Point of View Formerly and Today—A Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(3), 409. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10030409