*Warning: this content involves graphic subject matter that some may find disturbing. Reader discretion is advised.

If you are a Veteran, family member or caregiver in need of mental health support, the VAC Assistance Service is available to you 24/7, 365 days a year at no cost. Call 1-800-268-7708 to speak to a mental health professional right now.

Swissair Flight 111 took off from New York bound for Geneva when the crew discovered fire in the cockpit. They tried to dump fuel over St. Margaret’s Bay in preparation for an emergency landing at the nearest airport – Halifax International. Air traffic control lost contact with them at 10:24 p.m., moments before the plane hit the ocean nose first – eight kilometers from the Peggy’s Cove lighthouse.

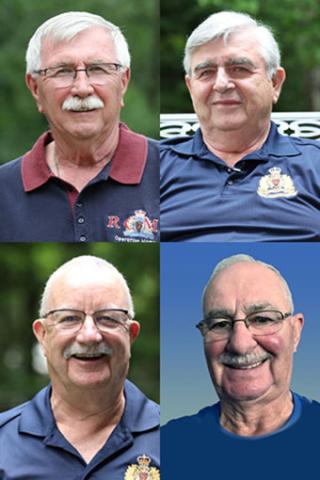

As hundreds of Nova Scotians were woken by early morning calls on 3 September 1998, RCMP Inspector (Ret’d) Neil Fraser, Staff Sgt. Vic Gorman, Superintendent Lee Fraser and Corporal Calvin Smith headed to Shearwater to embark on the biggest forensic identification project of their careers. They were a group of four senior Nova Scotia RCMP members with over 100 combined years of forensic identification experience who assembled in the early morning hours after the crash of Swissair Flight 111 off the coast of Peggy’s Cove.

RCMP Inspector (Ret’d) Neil Fraser memorized the Swissair passenger list, alphabetically.

He scoured the lists so many times for so many days, weeks and months that they were etched in his long-term memory.

After weeks of analyzing and sorting, Inspector (Ret’d) Neil Fraser has committed the Swissair Flight 111 passenger list to memory, alphabetically. The expertise he gained during the investigation was called on to aid in disaster victim identification after the 2004 tsunami in Phuket, Thailand.

Fraser was a forensics expert who had spent many hours testifying about blood spatter in Nova Scotia courtrooms. However, following the tragic crash of Swissair Flight 111, his expertise would be put to a different test.

In the months following the crash, he would often spend 12-16-hour days cataloguing DNA collected from human remains in Shearwater’s Hangar B. He and his team of RCMP forensic identification experts knew how important it was to the families to have something—anything—to bring home.

RCMP worked under Operation Homage alongside the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) teams whose mission was Operation Persistence. It was the largest multi-agency multi-national response and the most complex investigation in the history of the Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB).

"As the victims started to be identified through a number of ways, it really hit me, emotionally, one morning while I was checking a couple of body bags—these were no longer just numbers, these were people."

One of those real people came to Fraser’s attention as he read the Saturday morning newspaper. He came across a letter published in the paper, written by Nancy White, the American mother of 18-year-old passenger Rowenna White who had been heading to university in France aboard Swissair Flight 111. The grieving mother wrote to thank everyone involved in the investigation and recovery effort, but also to acknowledge she knew she might never be able to bury her daughter.

Rowenna was on Fraser’s mind when he reported for duty Monday morning at Shearwater’s Hangar B. “(That) morning, the first DNA result for the entire investigation came in—it was Rowenna White,” he said, his voice breaking with emotion.

“I went to (Superintendent Lee Fraser) and I said ‘bud, we’re going to do this.’”

RCMP Superintendent (Ret’d) Lee Fraser said he and his team wear the success of the Swissair Flight 111 investigation on their sleeves.

Lee Fraser is a tall, imposing Cape Bretoner with a deep baritone voice and kind eyes. The night Swissair Flight 111 crashed, he was Atlantic Canada’s lead on Forensic Identification.

"Our job was to identify these people. That turned out to be probably the most important and significant thing about the Swissair investigation, so the families could have closure."

Lee Fraser advised his team to take it one step at a time—reminding them they each had plenty of experience with crime scene exhibits. This was just a much larger scale. They had an overwhelming, monumental and emotional task laid out for them.

“We deal with exhibits all the time—we know how to catalogue them, we know the chain of continuity. This is just a lot of exhibits,’” Neil Fraser said.

It was tragic happenstance that brought the colleagues and friends together that night.

The Swissair RCMP ident team were seasoned Veterans with decades of expertise investigating homicides, suicides, suspicious deaths, and accidental deaths. Corporal Calvin Smith had experience investigating aviation disaster. He was part of the team of investigators after the crash of Arrow Air Flight 1285R in Gander, Newfoundland in 1985. His first advice on Swissair was that they immediately start a system to track every exhibit.

“We needed to document the processes,” Neil Fraser said.

“Those notes became part of the manual we developed that we took around the world—it was the most advanced manual in existence. It’s still used as a benchmark.”

They used scientific protocols with the dentistry and radiology teams using the four key elements of forensic identification—analyzing, comparing, evaluating, and verifying. It was an enormous puzzle and they all used innovative techniques to piece it all together.

For the first time in Canadian history, they were able to identify an entire family of five based on the father’s thumbprint. By confirming DNA via the thumbprint, they were able to half match the father’s DNA to find the three children. Then they took the other half of the children’s DNA to identify their mother.

Someone in an autopsy suite would shout “DNA” and Neil Fraser would fill a small test tube with muscle tissue or skin, number it and send it to Ottawa for testing. When the DNA could be matched to a passenger, the remains were placed in a body bag in a refrigerated truck on site. Each bag had a name that he had memorized. Once they had identified everyone, the remains were repatriated to family and loved ones. The unidentified remains were buried—surrounded by wild roses and the sea—off a footpath at the memorial at Bayswater.

RCMP Staff Sergeant. (Retd) Vic Gorman had spent his entire career around death - homicides, suicides, suspicious deaths, accidental deaths. He was often first on scene. His expertise was needed at Ground Zero in New York City after 9/11. He was diagnosed with PTSD in 2004. He and his wife Jan now work to support other Veterans with PTSD.

On the other side, forensics experts were collecting all the DNA they could find from every passenger. They were asking family members for samples, collecting it from toothbrushes, hairbrushes, even from a pair of wine glasses one couple left on their Paris table the night before they flew to New York.

“We were learning as we went along, identifying people with dental records, fingerprints, X-rays, DNA, even the serial numbers on knee and hip replacements,” Vic Gorman said.

The teams of nurses, doctors, CAF members and RCMP in the morgue got extremely close as they worked to complete their grueling task. It would have been too difficult to meet the families at that time, Gorman said. They pushed back when the Provincial Medical Examiner asked to bring them into the morgue.

“Because I had been involved in so much death prior to Swissair—I understood there were going to be some problems down the road,” Gorman explained.

“We fought against [the families coming in]. We just couldn’t do that—it was pretty devastating. We had people that had difficulty after, and still have difficulty to this day, so you didn’t want to be putting them in a situation where they’re going to break down.

"We did have some crying sessions during the investigation."

The outstanding work of the team over the following months to identify and repatriate the remains of every single one of the 229 victims secured the RCMP’s international reputation in disaster victim identification.

In the two and a half decades since the crash, each of them has given keynote addresses at international conferences. Their work also led to Canada joining INTERPOL’s disaster victim identification committee, and they rewrote the RCMP’s disaster manual (which is still used in police training today) along with sections of INTERPOL’s disaster victim identification manual.

The expertise they gained during the Swissair investigation led to each of their credentials as worldwide experts in the field. They were among the first forensic identification experts invited on scene at large-scale disasters that followed, such as the terrorist attacks on New York City on 11 September 2001 (Vic Gorman) and the tsunami in Phuket, Thailand in 2004 (Neil Fraser.)

Gorman was diagnosed with PTSD in 2004. Since his retirement, he and his wife Jan have worked to support Veterans with the same diagnosis. They were instrumental in the design and development of the Support and Advocacy Program in Nova Scotia and for the RCMP Veterans’ Association nationally.

“I have to deal with that every day of my life—you can’t hide from that stuff.”

Rowenna White’s name is inscribed with the other 228 passengers’ names on the Swissair Memorial at Bayswater, Nova Scotia.

The four Mounties are still good friends, gathering for dinner parties filled with old policing stories. They all still wear their Operation Homage shirts.

For all the sadness and heartache, some positive things came out of the Swissair investigation.

“I would never have missed the opportunity to be involved in that investigation, but I wouldn’t want to do it again,” Gorman said.

Lee Fraser said the men were very proud to say they identified every passenger in 105 days. The unforgettable experience softened his sharp edges from years of grisly police work and gave him a deeper appreciation for everything in his life.

“Twenty-five years later you can let that stiff upper lip down and some of your real feelings come out.

“It was quite a thing,” he said, his voice trailing off.

“And we got ‘er done—all of it.”

With courage, integrity and loyalty, Vic Gorman, Neil Fraser, Lee Fraser and Calvin Smith are leaving their mark. They are some of our RCMP members.