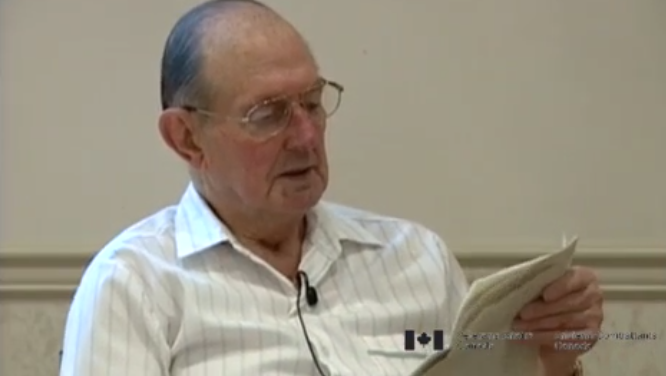

During the war I think that we generally had a good group of men,

in my particular situation. After you get into a prison camp,

everything changes, because our chief motivating drive is

self preservation. I’ll give you a good example of that.

When they would serve rice, they had a bowl and some would

just put it in lightly and skim it off, another section would

pack it in heavy and skim it off. Fellows would be seen saying,

“Oh, he has more than me,” or, “I have more than him.”

Once or twice we would get a little bun of bread in lieu of rice.

And we all had numbers, you know, and the fellow beside me,

for example, his number would be called and then my number

would be called. And I would go and say, number eleven, and

this other one, but on the way back to the bed I would be,

which of these weighs heavier. Whichever’s in my mind,

that was the one I took as number eleven, which was my number.

And that’s how it goes. Some fellows there were really hooked on

cigarettes. They’d sell their rations, while they’re starving

they’d still sell their rations. We had one fellow that,

his name was McQueen, he was the bone merchant.

They put horses lungs and bones from dead horses

in the soup that they’d make us sometimes. And if they ever

served this and if anybody had a bone, they would holler

for McQueen and he’d come round and appraise that bone.

This seems stupid, appraised that bone and said,

well it’s worth so many rations of rice, and he would take

that and start chawing on it because he figured he was

getting more calcium that way. He died, McQueen did.

Well, the officers were eating a lot better than we were,

and they didn’t seem to want to hide the fact.

Well, when you’re starving, food gets pretty predominant in your

thinking and actions, and that generated an awful lot of discord.

I, by that time, they would be flicking butts out, and they were

telling the chaps not to pick up their butts, but they didn’t

have any cigarettes. They, one occasion that I know of,

a fellow, and I can’t remember the offence, but he was put into a

one-room imprisonment, on half rations on a diet not considered

adequate for a human, but this happened.

Malnutrition was starting to set in very quickly. Matter of fact,

in Blackie Verreault’s diary, he wrote, after twenty days,

I think, as a prisoner of war, he doesn’t know how he’s going to

survive any more of this. And he had three, about three

years to go after that. There were no sanitary conditions.

The problem there was they had borehole latrines, you know,

and they, if you’ve ever seen a borehole latrine with

human excrement in there, and the maggots were

coming out of there, crawling down into our sleeping area.