Entitlement Eligibility Guideline (EEG)

Date created: 22 January 2025

ICD-11 code: DA04.6

VAC medical code: 52707 Salivary gland hypofunction disorder (xerostomia)

This publication is available upon request in alternate formats.

Full document – PDF Version

Definition

Any significant change in saliva flow is referred to as salivary gland dysfunction. Salivary gland dysfunction can be an increase (hyperfunction), or a decrease (hypofunction) in the flow of saliva.

- Salivary gland hyperfunction, an increase in the flow of saliva, is known as sialorrhea. A common symptom of sialorrhea is drooling.

- Salivary gland hypofunction (SGH) disorder is a significant measurable reduction in salivary flow, also known as hyposalivation. A common symptom of hyposalivation is oral dryness.

Xerostomia is the subjective feeling or sensation of a dry mouth. Xerostomia is a symptom of SGH disorder; however, individuals may also have the sensation of a dry mouth in the presence of normal salivary flow (for example, mouth breathing).

Certain circumstances such as with dehydration, mouth breathing, depression, and/or anxiety may add to the sensation or perception of a dry mouth/xerostomia as a symptom, rather than as an established diagnosis.

Note:

- While xerostomia and SGH disorder are distinct and independent, for the purposes of this entitlement eligibility guideline (EEG), a diagnosis of xerostomia will be accepted when it meets the diagnostic criteria for SGH disorder.

- Xerostomia in the absence of hyposalivation is not a disabling condition for Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC) disability benefits purposes.

Diagnostic standard

Diagnosis

VAC accepts the diagnosis(es) of salivary gland hypofunction disorder from the treating dentist (DDS, DMD).

Diagnostic considerations

A diagnosis of SGH disorder (hyposalivation) is confirmed in the presence of unstimulated salivary flow rate (sialometry) below 0.1 mL/min. Sialometry is a measurement of saliva flow.

Sialometry of unstimulated saliva flow is performed with a simple office procedure of collecting saliva at rest. The most commonly used sialometry method is the “draining method,” which is internationally accepted as a standard for measuring unstimulated whole saliva. Patients are instructed to first swallow all saliva then incline head forward and let saliva drip from lips into a prepared container, collector vial or graduated cylinder for five minutes. The collected saliva is then measured with a syringe and converted into mL/min.

Note: Where sialometry results are not available, a diagnosis of SGH disorder may be accepted if substantiated by clinical findings consistent with hyposalivation.

Anatomy and physiology

Saliva is a clear fluid containing mostly water with some electrolytes, mucus and enzymes. Saliva cleanses the oral cavity, maintains neutral pH by buffering acids, provides antibacterial and antifungal protection, and lubricates oral tissues.

Saliva is produced and excreted into the oral cavity by salivary glands with daily production between 0.5 and 1.5 liters.

- Unstimulated salivary flow is saliva secreted without stimulation. Normal unstimulated salivary flow rates range from 0.3 to 0.5 mL/min while awake, with a dramatic decrease during sleep.

- Stimulated salivary flow refers to the increase in saliva secretion with stimulation (chewing, taste, or smell) controlled by the autonomic nervous system. Sensory signals are sent to the salivation center in the brain by receptors in taste buds; tooth periodontal ligament(s); nose/olfactory (smell); and thermal sensors (temperature) which activate both parasympathetic and sympathetic innervation causing secretion of saliva from the salivary glands. The flow rate is dependent on the stimuli.

- Normal stimulated salivary flow rates range from 1.5 to 2.0 mL/min.

There are two types of salivary glands: the major salivary glands which produce most of the saliva, and minor salivary glands which produce less than 10% of saliva.

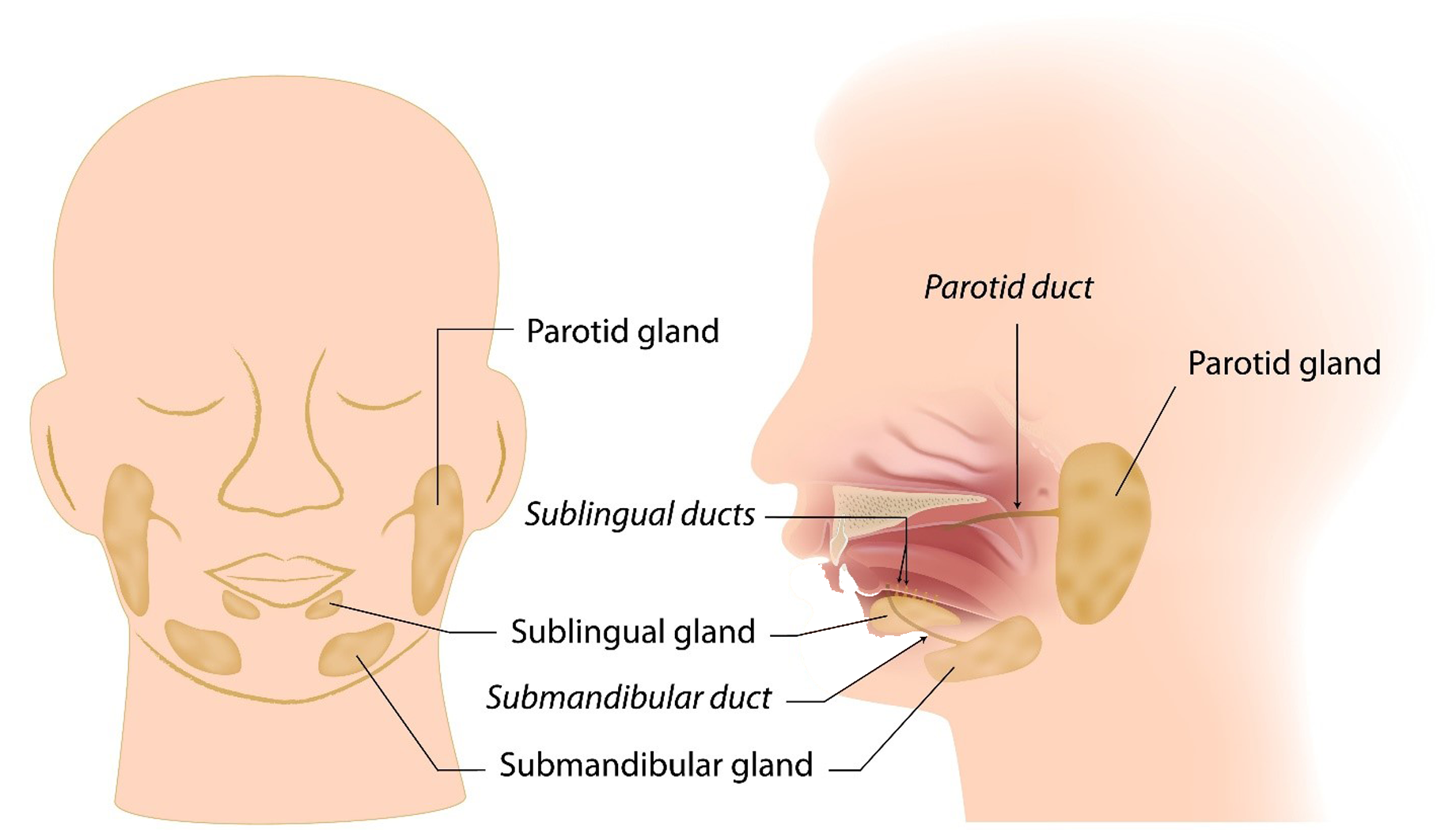

- Major salivary glands (Figure 1: Major salivary glands) include:

- Parotid glands are located bilaterally in front of the ears. They secrete saliva from ducts known as Stenson’s ducts opening near the upper second molar teeth. Parotid glands are the largest contributor to chewing-stimulated saliva secretion.

- Submandibular glands are located bilaterally below the mandible. They secrete saliva from ducts known as Wharton’s ducts opening below the tongue at the lingual frenum

- Sublingual glands are located bilaterally under the tongue, in front of the submandibular glands. They secrete saliva from multiple excretory ducts under the tongue directly into the floor of the mouth.

- Minor salivary glands are very small, numbering in the hundreds, and located throughout the mouth lining the oral mucosa of the lips, cheeks, tongue, and the roof of the mouth.

Figure 1: Major salivary glands

Clinical features

SGH disorder is a salivary gland dysfunction with a measurable reduction in salivary secretion (hyposalivation) causing oral dryness.

Clinical findings of oral dryness may include:

- mirror sticks to buccal mucosa and/or tongue

- frothy saliva

- tongue is lobulated/fissured

- tongue shows loss of papillae

- no saliva pools on floor of mouth

- glassy appearance of palatal mucosa

- smooth or altered gingiva

- food debris is found on palate (excluding debris under dentures)

- no saliva flow is noted with palpation of parotid gland and/or submandibular gland

- active or recently restored (within the last six months) cervical dental caries of more than two teeth.

SGH disorder can be caused by systemic diseases, medication, and radiotherapy of the head and neck.

Medication-induced SGH disorder/xerostomia occurs due to an adverse drug reaction to medications that affect the salivary glands. Certain medications that are anti-cholinergic, sympathomimetic, or diuretic in action, dependent on the dose, may affect the salivary glands. Any reduction in salivary flow is reversible and salivary gland function returns to normal after withdrawal of the medication.

Note: The prevalence of SGH disorder/xerostomia in patients receiving chemotherapy is about 50%, with salivary gland function typically restored within 6 to 12 months after treatment.

Radiation-induced SGH disorder/xerostomia occurs when the salivary gland tissues are damaged during radiotherapy of the head and neck. The tissue damage depends on the cumulative dose of radiation and the amount of salivary gland tissue included in the field. Salivary glands are affected within the first week of treatment and salivary secretion continues to decrease up to three months after radiotherapy. Doses higher than 60 Gray (Gy) usually lead to an irreversible severe SGH disorder.

Historically, epidemiological studies have not distinguished between the subjective feeling of dry mouth (xerostomia) and SGH disorder (hyposalivation). This has resulted in wide variation in the reported prevalence, with estimates ranging from 1% to 65% of the population. At the time of publication of this EEG, the scientific and health related literature estimates hyposalivation present in 10% to 20% of the adult population, with 30% of those individuals reporting xerostomia.

The prevalence of hyposalivation is more common in females and increases with age, particularly in individuals taking more than one medication.

Entitlement considerations

In this section

Section A: Causes and/or aggravation

Section B: Medical conditions which are to be included in entitlement/assessment

Section A: Causes and/or aggravation

For VAC entitlement purposes, the following factors are accepted to cause or aggravate the conditions included in the Definition section of this EEG, and may be considered along with the evidence to assist in establishing a relationship to service. The factors have been determined based on a review of up-to-date scientific and medical literature, as well as evidence-based medical best practices. Factors other than those listed may be considered, however consultation with a disability consultant or medical advisor is recommended.

The timelines cited below are for guidance purposes. Each case should be adjudicated on the evidence provided and its own merits.

Factors

- Having systemic disease at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of SGH disorder. Examples include but are not limited to:

- Sjögren's syndrome

- cystic fibrosis

- primary biliary cholangitis

- graft-versus-host disease

- immunoglobulin G4-related sclerosing disease

- amyloidosis

- sarcoidosis

- tuberculosis involving the salivary gland(s)

- human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

- hepatitis C

- end-stage renal failure requiring dialysis.

- Having hormonal disturbance at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of SGH disorder. Examples include:

- bilateral oophorectomy

- menopause.

- Having a salivary gland condition at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of SGH disorder. Examples include:

- salivary gland aplasia or agenesis

- parotidectomy.

- Receiving external beam radiation therapy to the head and neck region involving one or more of the major salivary glands prior to the clinical onset or aggravation of SGH disorder.

- Using prescribed medication known to cause or contribute to SGH disorder prior to clinical onset or aggravation.

For VAC purposes, medications considered are those causing adverse drug reactions affecting the salivary glands. These medications include, but are not limited to, the following:

- urological overactive bladder:

- oxybutynin

- tolterodine

- solifenacin.

- antidepressants and antipsychotics:

- amitriptyline

- bupropion

- citalopram

- duloxetine

- escitalopram

- fluoxetine

- imipramine

- lithium

- mirtazapine

- olanzapine

- paroxetine

- quetiapine

- sertraline

- trazodone

- venlafaxine.

- urological overactive bladder:

- Inability to obtain appropriate clinical management of SGH disorder.

Section B: Medical Conditions which are to be included in entitlement/assessment

Section B provides a list of diagnosed medical and dental conditions which are considered for VAC purposes to be included in the entitlement and assessment of SGH disorder (xerostomia).

- Hyposalivation

- Hypoptyalism

Section C: Common medical and dental conditions which may result, in whole or in part, from salivary gland hypofunction disorder (xerostomia) and/or its treatment

Section C is a list of conditions which can be caused or aggravated by SGH disorder (xerostomia) and/or its treatment. Conditions listed in Section C are not included in the entitlement and assessment of SGH disorder (xerostomia). A consequential entitlement decision may be considered where the individual merits and the medical evidence of the case support a consequential relationship.

Conditions other than those listed in Section C may be considered; consultation with a disability consultant or dental advisor is recommended.

- Dental caries

- Oral candidiasis (fungal infections)

Links

Related VAC guidance and policy:

- Pain and Suffering Compensation – Policies

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police Disability Pension Claims – Policies

- Dual Entitlement – Disability Benefits – Policies

- Establishing the Existence of a Disability – Policies

- Disability Benefits in Respect of Peacetime Military Service – The Compensation Principle – Policies

- Disability Benefits in Respect of Wartime and Special Duty Service – The Insurance Principle – Policies

- Disability Resulting from a Non-Service Related Injury or Disease – Policies

- Consequential Disability – Policies

- Benefit of Doubt – Policies

References as of 22 January 2025

Agha-Hosseini, F., & Mirzaii-Dizgah, I. (2012). Unstimulated saliva 17β-estradiol and xerostomia in menopause. Gynecological Endocrinology: The Official Journal of the International Society of Gynecological Endocrinology, 28(3), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.3109/09513590.2011.593668

Agha-Hosseini, F., & Moosavi, M.-S. (2013). An evidence-based review literature about risk indicators and management of unknown-origin xerostomia. Journal of Dentistry (Tehran, Iran), 10(3), Article 3.

Agostini, B. A., Cericato, G. O., Silveira, E. R. da, Nascimento, G. G., Costa, F. D. S., Thomson, W. M., & Demarco, F. F. (2018). How common is dry mouth?Systematic review and meta-regression analysis of prevalence estimates. Brazilian Dental Journal, 29(6), Article 6. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103- 6440201802302

Alzoubi, E. E. (2017). Oral manifestations of menopause. Journal of Dental Health, Oral Disorders & Therapy, 7(4), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.15406/jdhodt.2017.07.00247

Apessos, I., Andreadis, D., Steiropoulos, P., Tortopidis, D., & Angelis, L. (2020). Investigation of the relationship between sleep disorders and xerostomia. Clinical Oral Investigations, 24(5), Article 5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-019- 03029-1

Atkinson, J. C., Grisius, M., & Massey, W. (2005). Salivary hypofunction and xerostomia: Diagnosis and treatment. Dental Clinics of North America, 49(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cden.2004.10.002

Atkinson, J. C., Travis, W. D., Pillemer, S. R., Bermudez, D., Wolff, A., & Fox, P. C. (1990). Major salivary gland function in primary Sjögren’s syndrome and its relationship to clinical features. The Journal of Rheumatology, 17(3), Article 3.

Benn, A., Broadbent, J., & Thomson, W. (2015). Occurrence and impact of xerostomia among dentate adult New Zealanders: Findings from a national survey. Australian Dental Journal, 60(3), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.1111/adj.12238

Billings, M., Dye, B. A., Iafolla, T., Baer, A. N., Grisius, M., & Alevizos, I. (2016). Significance and implications of patient-reported xerostomia in Sjögren’s Syndrome: Findings From the National Institutes of Health Cohort. EBioMedicine, 12, 270–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.09.005

Blanco, V., Salmerón, M., Otero, P., & Vázquez, F. L. (2021). Symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress and prevalence of major depression and Its predictors in female university students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), Article 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115845

Bolstad, A. I., & Skarstein, K. (2016). Epidemiology of Sjögren’s Syndrome-from an oral perspective. Current Oral Health Reports, 3(4), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40496-016-0112-0

Bulthuis, M. S., Jan Jager, D. H., & Brand, H. S. (2018). Relationship among perceived stress, xerostomia, and salivary flow rate in patients visiting a saliva clinic. Clinical Oral Investigations, 22(9), Article 9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-018- 2393-2

Ciesielska, A., Kusiak, A., Ossowska, A., & Grzybowska, M. E. (2021). Changes in the oral cavity in menopausal women-A narrative review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010253

Davies, S. J. C., Underhill, H. C., Abdel-Karim, A., Christmas, D. M., Bolea-Alamanac, B. M., Potokar, J., Herrod, J., & Prime, S. S. (2016). Individual oral symptoms in burning mouth syndrome may be associated differentially with depression and anxiety. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica, 74(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.3109/00016357.2015.1100324

Dry mouth scale launched. (2011). British Dental Journal, 211(8), Article 8. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.884

Escobar, A., & P. Aitken-Saavedra, J. (2019). Xerostomia: An update of causes and treatments. In I. Adadan Güvenç (Ed.), Salivary Glands—New Approaches in Diagnostics and Treatment. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.72307

Farronato, G., & Maspero, C. (2012). Menopause: Changes in the mouth cavity and preventive strategies. Journal of Womens Health Care, 01(01), Article 01.

Gholami, N., Hosseini Sabzvari, B., Razzaghi, A., & Salah, S. (2017). Effect of stress, anxiety and depression on unstimulated salivary flow rate and xerostomia. Journal of Dental Research, Dental Clinics, Dental Prospects, 11(4), Article 4.

Gómez, B., Hernández Vallejo, G., Arriba de la Fuente, L., López Cantor, M., Díaz, M., & López Pintor, R. M. (2006). The relationship between the levels of salivary cortisol and the presence of xerostomia in menopausal women. A preliminary study. Medicina Oral, Patologia Oral Y Cirugia Bucal, 11(5), Article 5.

Grover, S. S., & Rhodus, N. L. (2016). Xerostomia and depression. Northwest Dentistry, 95(3), Article 3.

Guggenheimer, J., & Moore, P. A. (2003). Xerostomia. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 134(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0018

Gupta, A., Epstein, J. B., & Sroussi, H. (2006). Hyposalivation in elderly patients. Journal (Canadian Dental Association), 72(9), Article 9.

Hopcraft, M. S., & Tan, C. (2010). Xerostomia: An update for clinicians. Australian Dental Journal, 55(3), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2010.01229.x

Hoseini, A., Mirzapour, A., Bijani, A., & Shirzad, A. (2017). Salivary flow rate and xerostomia in patients with type I and II diabetes mellitus. Electronic Physician, 9(9), Article 9. https://doi.org/10.19082/5244

Jacob, L. E., Krishnan, M., Mathew, A., Mathew, A. L., Baby, T. K., & Krishnan, A. (2022). Xerostomia—A comprehensive review with a focus on mid-life Health. Journal of Mid-Life Health, 13(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.4103/jmh.jmh_91_21

Jager, D. H. J., Bots, C. P., Forouzanfar, T., & Brand, H. S. (2018). Clinical oral dryness score: Evaluation of a new screening method for oral dryness. Odontology, 106(4), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10266-018-0339-4

Jensen, S. B., & Vissink, A. (2014). Salivary gland dysfunction and xerostomia in Sjögren’s syndrome. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America, 26(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coms.2013.09.003

Jindal, R., Shenoy, N., Udayalakshmi, J., & Baliga, S. (2016). Correlation between xerostomia, hyposalivation, and oral microbial load with glycemic control in type 2 diabetic patients. World Journal of Dentistry, 7(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10015-1370

Johansson, A.-K., Omar, R., Mastrovito, B., Sannevik, J., Carlsson, G. E., & Johansson, A. (2022). Prediction of xerostomia in a 75-year-old population: A 25-year longitudinal study. Journal of Dentistry, 118, 104056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2022.104056

Kabasakal, Y., Kitapcioglu, G., Turk, T., Oder, G., Durusoy, R., Mete, N., Egrilmez, S., & Akalin, T. (2006). The prevalence of Sjögren’s syndrome in adult women. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology, 35(5), Article 5. https://doi.org/10.1080/03009740600759704

Kumagami, H., & Onitsuka, T. (1993). Estradiol and testosterone in minor salivary glands of Sjögren’s syndrome. Auris, Nasus, Larynx, 20(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0385-8146(12)80241-0

Lago, M. L. F., de Oliveira, A. E. F., Lopes, F. F., Ferreira, E. B., Rodrigues, V. P., & Brito, L. M. O. (2015). The influence of hormone replacement therapy on the salivary flow of post-menopausal women. Gynecological Endocrinology: The Official Journal of the International Society of Gynecological Endocrinology, 31(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.3109/09513590.2014.959918

Lee, Y.-H., An, J.-S., & Chon, S. (2019). Sex differences in the hypothalamic-pituitary- adrenal axis in patients with burning mouth syndrome. Oral Diseases, 25(8), Article 8. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.13195

Maciel, G., Crowson, C. S., Matteson, E. L., & Cornec, D. (2017). Prevalence of primary Sjögren’s Syndrome in a US population-based cohort. Arthritis Care & Research, 69(10), Article 10. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23173

Makeeva, I. M., Budina, T. V., Turkina, A. Y., Poluektov, M. G., Kondratiev, S. A., Arakelyan, M. G., Signore, A., & Amaroli, A. (2021). Xerostomia and hyposalivation in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea. Clinical Otolaryngology, 46(4), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.1111/coa.13735

Mignogna, M. D., Fedele, S., Lo Russo, L., Lo Muzio, L., & Wolff, A. (2005). Sjögren’s syndrome: The diagnostic potential of early oral manifestations preceding hyposalivation/xerostomia. Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine: Official Publication of the International Association of Oral Pathologists and the American Academy of Oral Pathology, 34(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0714.2004.00264.x

Minicucci, E., Pires, R., Vieira, R., Miot, H., & Sposto, M. (2013). Assessing the impact of menopause on salivary flow and xerostomia. Australian Dental Journal, 58(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.1111/adj.12057

Miranda-Rius, J., Brunet-Llobet, L., Lahor-Soler, E., & Farré, M. (2015). Salivary secretory disorders, inducing drugs, and clinical management. International Journal of Medical Sciences, 12(10), Article 10. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijms.12912

Mortazavi, H., Baharvand, M., Movahhedian, A., Mohammadi, M., & Khodadoustan, A. (2014). Xerostomia due to systemic disease: A review of 20 conditions and mechanisms. Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research, 4(4), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.4103/2141-9248.139284

Navazesh, M., Christensen, C., & Brightman, V. (1992). Clinical criteria for the diagnosis of salivary gland hypofunction. Journal of Dental Research, 71(7), Article 7. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220345920710070301

Niklander, S., Veas, L., Barrera, C., Fuentes, F., Chiappini, G., Marshall, M., & Universidad Andres Bello, Chile. (2017). Risk factors, hyposalivation and impact of xerostomia on oral health-related quality of life. Brazilian Oral Research, 31(0), Article 0. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-3107bor-2017.vol31.0014

Orellana, M. F., Lagravère, M. O., Boychuk, D. G. J., Major, P. W., & Flores-Mir, C. (2006). Prevalence of xerostomia in population-based samples: A systematic review. Journal of Public Health Dentistry, 66(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752- 7325.2006.tb02572.x

Osailan, S., Pramanik, R., Shirodaria, S., Challacombe, S. J., & Proctor, G. B. (2011). Investigating the relationship between hyposalivation and mucosal wetness. Oral Diseases, 17(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1601-0825.2010.01715.x

Parinda, I. A., Siregar, M. F. G., Hartono, H., Sitepu, M., Munthe, I. G., Edianto, D., & Eyanoer, P. C. (2020). Correlation between estradiol serum levels with xerostomia inventory score on menopausal women. International Journal of Current Pharmaceutical Research, 122–126. https://doi.org/10.22159/ijcpr.2020v12i4.39098

Patel, R., & Shahane, A. (2014). The epidemiology of Sjögren’s syndrome. Clinical Epidemiology, 6, 247–255. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S47399

Pedersen, A. M. L., Sørensen, C. E., Proctor, G. B., Carpenter, G. H., & Ekström, J. (2018). Salivary secretion in health and disease. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 45(9), Article 9. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12664

Pinto, A. (2014). Management of xerostomia and other complications of Sjögren’s syndrome. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America, 26(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coms.2013.09.010

Plemons, J. M., Al-Hashimi, I., & Marek, C. L. (2014). Managing xerostomia and salivary gland hypofunction. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 145(8), Article 8. https://doi.org/10.14219/jada.2014.44

Ramírez Sepúlveda, J. I., Kvarnström, M., Brauner, S., Baldini, C., & Wahren-Herlenius, M. (2017). Difference in clinical presentation between women and men in incident primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Biology of Sex Differences, 8, 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13293-017-0137-7

Rischmueller, M., Tieu, J., & Lester, S. (2016). Primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology, 30(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2016.04.003

Sepúlveda, J. I., Kvarnström, M., Eriksson, P., Mandl, T., Norheim, K. B., Johnsen, S. J., Hammenfors, D., Jonsson, M. V., Skarstein, K., Brun, J. G., Rönnblom, L., Forsblad-d’Elia, H., Magnusson Bucher, S., Baecklund, E., Theander, E., Omdal, R., Jonsson, R., Nordmark, G., & Wahren-Herlenius, M. (2017). Long-term follow- up in primary Sjögren’s syndrome reveals differences in clinical presentation between female and male patients. Biology of Sex Differences, 8(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13293-017-0146-6

Shinohara, C., Ito, K., Takamatsu, K., Ogawa, M., Kajii, Y., Nohno, K., Sugano, A., Funayama, S., Katakura, A., Nomura, T., & Inoue, M. (2021). Factors associated with xerostomia in perimenopausal women. The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research, 47(10), Article 10. https://doi.org/10.1111/jog.14963

Shirzaiy, M., & Bagheri, F. (2016). Prevalence of xerostomia and its related factors in patients referred to Zahedan dental school in Iran. Dental Clinical and Experimental Journal, 2(1), Article 1.

Simms, M. L., Kuten-Shorrer, M., Wiriyakijja, P., Niklander, S. E., Santos-Silva, A. R., Sankar, V., Kerr, A. R., Jensen, S. B., Riordain, R. N., Delli, K., & Villa, A. (2023). World workshop on oral medicine VIII: Development of a core outcome set for dry mouth: a systematic review of outcome domains for salivary hypofunction. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Oral Radiology, 135(6), Article 6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oooo.2022.12.018

Sreebny, L. M. (1987). Xerostomia: A neglected symptom. Archives of Internal Medicine, 147(7), Article 7. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1987.00370070145022

Suri, V., & Suri, V. (2014). Menopause and oral health. Journal of Mid-Life Health, 5(3), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-7800.141187

Tan, E. C. K., Lexomboon, D., Sandborgh-Englund, G., Haasum, Y., & Johnell, K. (2018). Medications that cause dry mouth as an adverse effect in older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 66(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15151

Thomas, E., Hay, E. M., Hajeer, A., & Silman, A. J. (1998). Sjögren’s syndrome: A community-based study of prevalence and impact. British Journal of Rheumatology, 37(10), Article 10. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/37.10.1069

Thompson, G., & Parmar, N. (2021). Adverse drug reactions: Part 1 xerostomia. BDJ Student, 28(3), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41406-021-0226-2

van der Reijden, W. A., Vissink, A., Veerman, E. C., & Amerongen, A. V. (1999). Treatment of oral dryness related complaints (xerostomia) in Sjögren’s syndrome. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 58(8), Article 8. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.58.8.465

Veerabhadrappa, S. K. (2016). Evaluation of xerostomia in different psychological disorders: An observational study. Journal of Clinical AND Diagnostic Research. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2016/19020.8437

Veterans Affairs Canada (2024). Major Salivary Glands. License purchased for use from Salivary Glands Royalty Free SVG, Cliparts, Vectors, and Stock Illustration. Image 16625665. (123rf.com)

Villa, A., Connell, C. L., & Abati, S. (2015). Diagnosis and management of xerostomia and hyposalivation. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management, 11, 45–51. https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S76282

Villa, A., Nordio, F., & Gohel, A. (2016). A risk prediction model for xerostomia: A retrospective cohort study. Gerodontology, 33(4), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.1111/ger.12214

Vivino, F. B. (2017). Sjogren’s syndrome: Clinical aspects. Clinical Immunology (Orlando, Fla.), 182, 48–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2017.04.005

Wang, L., Zhu, L., Yao, Y., Ren, Y., & Zhang, H. (2021). Role of hormone replacement therapy in relieving oral dryness symptoms in postmenopausal women: A case control study. BMC Oral Health, 21(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-021-01966-6

Wolff, A., Joshi, R. K., Ekström, J., Aframian, D., Pedersen, A. M. L., Proctor, G., Narayana, N., Villa, A., Sia, Y. W., Aliko, A., McGowan, R., Kerr, A. R., Jensen, S. B., Vissink, A., & Dawes, C. (2017). A guide to medications inducing salivary gland dysfunction, xerostomia, and subjective sialorrhea: A systematic review sponsored by the world workshop on oral medicine VI. Drugs in R&D, 17(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40268-016-0153-9

World Health Organization. (2022). ICD-11: International classification of diseases (11th revision). https://icd.who.int/