Entitlement Eligibility Guideline (EEG)

Date created: 15 April 2025

ICD-11 code: DA0E.8

VAC medical code: 52469

This publication is available upon request in alternate formats.

Full document – PDF Version

Definition

Temporomandibular disorder (TMD) is a diagnostic term for a group of musculoskeletal conditions that affect the muscles of mastication and/or the temporomandibular joint(s) (TMJ). It is not a specific diagnosis.

Note: Temporomandibular joint dysfunction (TMJD) is a term used prior to 1985 to describe symptoms around the TMJ area. This was changed to TMD in the early 1980’s to include chronic conditions affecting the muscles of mastication and/or TMJ(s).

For the purposes of this entitlement eligibility guideline (EEG), the following TMDs are included:

- Masticatory muscle conditions:

- masticatory muscle pain conditions.

- Temporomandibular joint conditions:

- temporomandibular joint pain conditions

- temporomandibular joint disorders

- temporomandibular degenerative joint disease

- mandibular condylar fracture.

Diagnostic standard

Diagnosis

Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC) accepts the diagnosis(es) of TMD(s) from the treating dentist (doctor of dental surgery or doctor of dental medicine) or dentist specialist (for example, oral surgeon, oral medicine specialist).

Diagnostic considerations

- Diagnosis(es) of TMDs is based on the published diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (DC/TMD) found on the website of the International Network for Orofacial Pain and Related Disorders Methodology (INfORM). DC/TMD is a universally accepted, reliable, evidence-based, diagnostic system for common TMDs.

- For VAC entitlement purposes, diagnosis(es) of the specific TMD is required.

Note: At the time of the publication of this EEG, the health-related expert opinion and scientific evidence does not support electrodiagnostic testing for diagnosis and/or treatment of TMDs. For VAC entitlement purposes, clinical information reported from electrodiagnostic testing is not accepted; this includes jaw-tracking devices, electromyography (EMG), thermography, sonography (doppler), and joint vibration analysis (JVA).

Anatomy and physiology

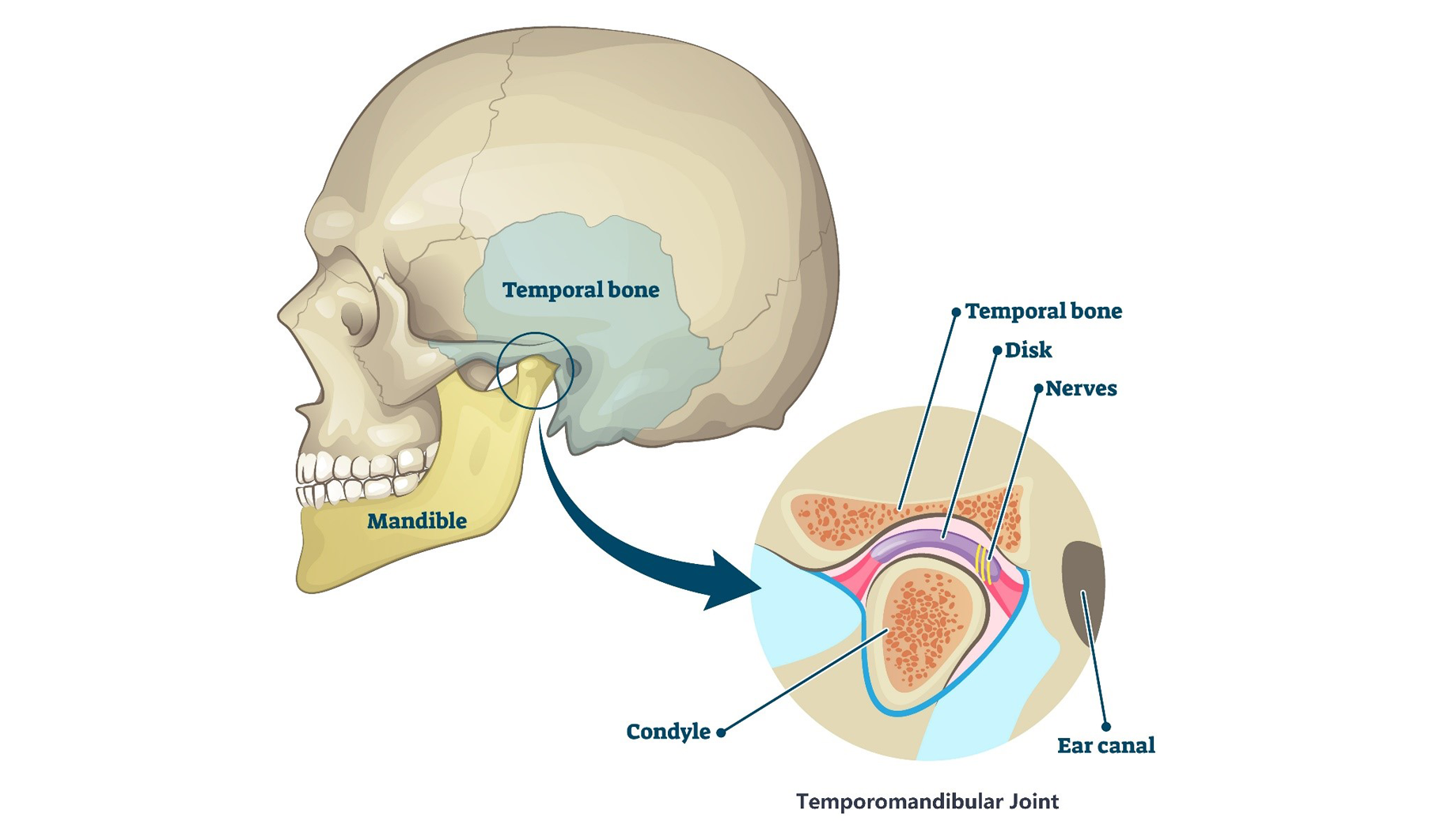

Bilateral TMJs connect the mandible to the skull. Each TMJ consists of a mandibular condyle, an articular disc, and temporal bones (Figure 1: Temporomandibular joint anatomy). Synovial fluid provides lubrication to the joint during movement.

- The mandibular condyle(s) are the bilateral rounded ends of the mandible.

- The temporal bones form the sides and base of skull and include glenoid fossa(e) and articular eminence(s).

- The articular disc separates the temporal bone and the mandibular condyle providing stability, shock absorption and allowing for smooth movement.

Figure 1: Temporomandibular joint anatomy

Unlike most synovial joints, the articular (bony) surfaces of the TMJ are lined with fibrocartilage instead of hyaline cartilage. This is an important distinction as fibrocartilage is better able to absorb forces and has a greater ability to heal and repair than hyaline cartilage.

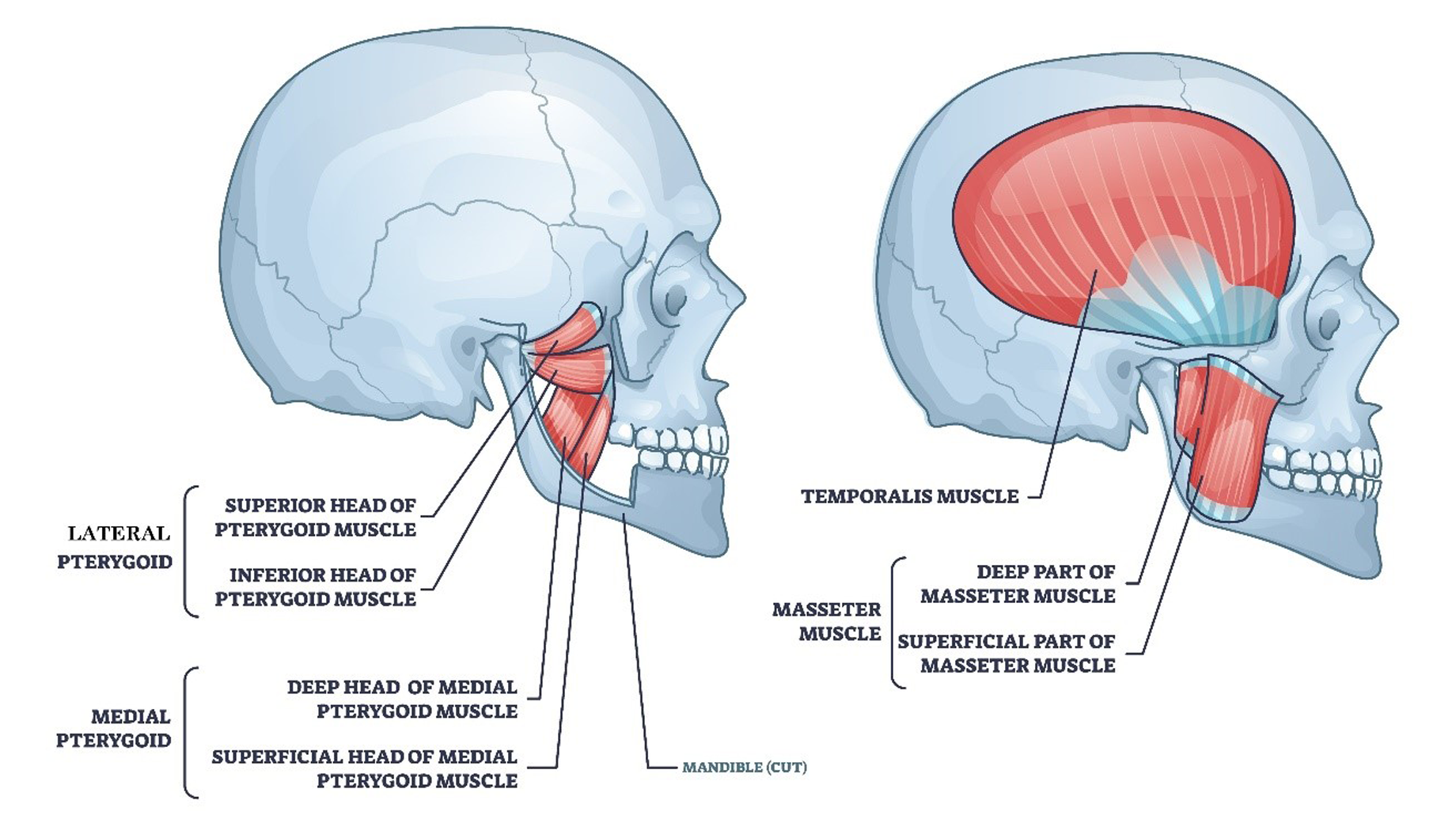

Mandibular movement is produced by muscles of mastication. These are four bilateral muscles attached to the mandible on each side of the skull (Figure 2: Masticatory muscles):

- temporalis muscles

- masseter muscles

- medial pterygoid muscles

- lateral pterygoid muscles.

Figure 2: Masticatory muscles

Mouth opening, closing, and chewing requires simultaneous bilateral coordination of the muscles of mastication with the mandibular condyles, temporal bones, and the articular discs.

Prevalence of TMD symptoms in the general population ranges from 5% to 12% primarily affecting young to middle-aged adults, more commonly presenting in females.

Masticatory muscle conditions

In this section

Definition

For the purposes of this EEG, the following diagnoses are equivalent masticatory muscle conditions:

- myalgia of the muscles of mastication

- local myalgia of the muscles of mastication

- myofascial pain of the muscles of mastication

- myofascial pain of the muscles of mastication with referral.

Diagnostic standard

For VAC entitlement purposes:

- Diagnosis(es) of the specific TMD condition(s) affecting the masticatory muscles is required.

- Diagnosis(es) of TMD condition(s) is considered bilateral. Identification of right and/or left is accepted but not required.

Clinical features

Myalgia of the muscles of mastication is chronic pain originating from the masticatory muscles which is increased upon palpation and with jaw movement.

The primary clinical features of myalgia of the muscles of mastication include:

- symptoms of chronic persistent daily pain in the jaw muscles, temple, or area around the ear

- increased pain with jaw movement (mouth opening and chewing)

- pain to palpation of the temporalis and/or masseter muscles on exam.

While the pathophysiology of masticatory myalgia remains unclear, current evidence suggests a complex multifactorial interaction at the level of the muscle, the peripheral nervous system, central nervous system, and autonomic nervous system.

Note: Bruxism is not a TMD masticatory muscle condition. These two conditions have distinct diagnostic criteria and clinical signs and symptoms. Bruxism is very common and the intensity and frequency can fluctuate resulting in transient tension or tenderness of the masticatory muscles and/or an acute inflammation of the TMJ lining.

Entitlement considerations

Section A: Causes and/or aggravation of masticatory muscle conditions

For VAC entitlement purposes, the following factors are accepted to cause or aggravate masticatory muscle conditions, and may be considered along with the evidence to assist in establishing a relationship to service. The factors have been determined based on a review of up-to-date scientific, medical and dental literature, as well as evidence-based medical and dental best practices. Factors other than those listed may be considered, however consultation with a disability consultant or dental advisor is recommended.

The timelines cited below are for guidance purposes. Each case should be adjudicated on the evidence provided and its own merits.

Note: Masticatory muscle conditions may present as part of a chronic pain disorder, such as fibromyalgia. Where medical evidence indicates that a masticatory muscle condition is presenting as part of a primary condition, the masticatory muscle condition is included in the entitlement and assessment of the primary condition.

Factors

- Experiencing blunt trauma to the mandible (chin) at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of the masticatory muscle condition. Examples include:

- sports injury

- fall

- assault

- motor vehicle accident.

- Having wide or prolonged mouth opening at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of the masticatory muscle condition. Examples include:

- dental procedure (for example, third molar extraction)

- long dental appointment

- oral intubation during general anesthesia

- yawning

- biting into an apple.

- Having a malocclusion(s) which interferes with smooth coordinated mandibular movement prior to the clinical onset or aggravation of the masticatory muscle condition. Examples include:

- deep bite malocclusions (overjet greater than 6mm)

- open bite malocclusions

- steep slope of the articular eminence

- cross bite malocclusions

- abnormal curve of Spee

- abnormal curve of Wilson

- asymmetric or damaged condyles.

- Exhibiting a chronic oral behaviour as a symptom of a diagnosed clinically significant psychiatric condition prior to clinical onset or aggravation of the masticatory muscle condition as supported by the treating dentist or dentist specialist.

Note: At the time of the publication of this EEG, the health-related expert opinion and scientific evidence indicates signs and symptoms associated with a diagnosed clinically significant psychiatric condition, other than chronic oral behaviours are not causal or aggravating factors for masticatory muscle conditions.

- Having chronic bruxism over an extended period of time not controlled with treatment prior to the clinical onset or aggravation of the masticatory muscle condition.

- Inability to obtain appropriate clinical management of the masticatory muscle condition.

Note: Section B and Section C are the same for all TMDs and can be found under Entitlement considerations below.

Temporomandibular joint conditions

In this section

Definition

For the purposes of this EEG, the following conditions are included in temporomandibular joint (TMJ) conditions:

- TMJ pain conditions

- TMJ arthralgia

- TMJ disorders

- TMJ disc displacements

- hypermobility of the TMJ(s)

- temporomandibular degenerative joint disease

- TMJ osteoarthritis

- mandibular condylar fracture.

Note: TMJ conditions other than those listed may be considered, and should be adjudicated on the evidence provided and their own merits. Consultation with a disability consultant or dental advisor is recommended.

Diagnostic standard

For VAC entitlement purposes:

- Diagnosis(es) of the specific TMD condition(s) affecting TMJ(s) is required.

- Diagnosis(es) of TMD condition(s) is considered bilateral; dentification of right and/or left is accepted but not required.

- Panoramic tomography (pan radiograph) is not diagnostic for the presence of TMJ pathology or disease due to the normal anatomical variation of mandibular condyles.

- Diagnosis of temporomandibular degenerative joint disease (osteoarthritis) requires cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) or conventional computed tomogram (CT).

- While not required for VAC entitlement purposes, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the TMJ(s) may be used to confirm diagnosis of TMJ disorders (disc displacement and/or hypermobility disorders).

Clinical features

TMJ arthralgia is chronic pain originating from the lining of the TMJ(s) which is increased upon palpation and with jaw movement. Historically, TMJ arthralgia has been referred to as synovitis, capsulitis and retrodiscitis.

The primary clinical features of TMJ arthralgia include:

- Daily pain reported in and/or in front of the ear(s); may be single or recurrent within any day, each lasting at least 30 minutes and with a total duration within the day of at least two hours; present for more than six months.

- Pain increases with any jaw movement or function (opening and chewing).

- Pain to palpation of one or both TMJ(s) on exam where standardization of compression force and duration of palpation of TMJ(s) is one pound of pressure for two seconds.

TMJ arthralgia is typically an acute short term condition often due to trauma (blow to chin) that resolves with a period of joint rest and anti-inflammatory medication. Chronic TMJ arthralgia is diagnosed when symptoms persist longer than six months.

Note: TMJ arthritis is joint pain as described for arthralgia with the additional clinical characteristics of inflammation or infection, including: edema, erythema, and/or increased temperature. This will be discussed in more detail in the TMJ disease (osteoarthritis) section.

TMJ disorders, historically referred to as TMJ dysfunction, are characterized by an abnormal condyle-disc position.

For the purposes of this EEG, two categories of TMJ disorders are included:

- TMJ disc displacements

- hypermobility of the TMJ(s).

TMJ disc displacements and hypermobility may occur as part of normal aging and/or during pregnancy due to generalized joint laxity or loss of elasticity.

TMJ disc displacement describes the anterior displacement of the articular disc off the condyle. The disc displacement occurs when the ligaments holding the articular disc in place are elongated, allowing movement of the disc from its normal relationship between the mandibular condyle and the glenoid fossa. Individuals can usually relate it to a specific event.

There are three types of disc displacement:

- Disc displacement with reduction occurs when the ligaments holding the articular disc in place are elongated allowing the articular disc to move anteriorly off the mandibular condyle in the closed mouth position. The disc reduces (pops back on the condyle) with mouth opening causing a clicking, popping, or snapping noise; deviation of the mandible to the affected side on mouth opening may also be present.

While TMJ noise is common, disc displacement with reduction is typically asymptomatic with a normal range of mouth opening and no therapy beyond education is required.

- Disc displacement with reduction with intermittent locking occurs when the disc occasionally does not reduce on mouth opening and remains anterior to the condyle during mouth opening and closing. When the disc does not reduce, it blocks condyle movement causing limited mouth opening or “locking” intermittently.

- Disc displacement without reduction occurs when the anteriorly displaced disc does not reduce and remains anterior to the condyle during mouth opening and closing. In the initial acute phase, there may be pain with function localized to the preauricular area and limited mouth opening (often described as jaw locking or catching). This typically resolves as the joint adapts, allowing for normal mouth opening with no ongoing functional impairment.

Hypermobility of the TMJ describes abnormal or excessive forward movement of the condyle and articular disc out of the glenoid fossa and over or beyond the articular eminence during mouth opening.

TMJ hypermobility disorders are uncommon, generally acute and in most cases, the joint adapts to allow for normal mouth closure.

There are two types of TMJ hypermobility:

- Subluxation of the TMJ is a partial TMJ dislocation. This occurs when the disc-condyle complex moves too far forward on the articular eminence during mouth opening with reports of the jaw getting stuck or sticking open; individuals are able to close their mouth with a maneuver (self-reduce).

- Luxation of the TMJ is a complete TMJ dislocation with loss of articulating function. This occurs when the disc-condyle complex moves forward excessively, going beyond the articular eminence, and gets stuck or sticks in a wide open mouth position. Mouth closing does not occur as the condyles cannot return to the glenoid fossa. This is referred to as an open lock. There is often a simultaneous muscle spasm blocking movement of the mandibular condyle back over the articular eminence. Treatment requires a specific manipulative maneuver by a clinician and most cases require sedation to manipulate the jaw back into position.

Temporomandibular degenerative joint disease (DJD) is a chronic progressive disease characterized by the deterioration of the articular disc with osseous (bone) changes in the condyle and/or articular eminence.

TMJ osteoarthritis (TMJOA) describes temporomandibular DJD with joint pain (arthralgia). Development of TMJOA is a normal part of aging over the age of 50 years.

Note:

- For the purposes of this EEG, the terms “osteoarthritis” and “osteoarthrosis” are considered synonymous.

- While the TMJ(s) may be affected by infectious, rheumatic, or metabolic (psoriatic) arthritis, it is uncommon and not included in this EEG.

The clinical features of TMJOA include:

- TMJ noise referred to as ‘crepitus’ (crunching, grinding, or grating noises) present with jaw movement

- daily pain in the TMJ(s) which increases with jaw movement

- limitation in opening and difficulty chewing

- pain with palpation of the TMJ(s) on clinical exam

- anterior open bite present with bilateral TMJOA

- cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) or conventional computed tomogram (CT) imaging shows the presence of subchondral cyst(s), erosion(s), or osteophyte(s).

Note: Flattening and/or cortical sclerosis are considered indeterminant findings for DJD.

A mandibular condylar fracture is an intra-articular fracture of the head or neck of the mandibular condyle, also known as a fracture of the mandibular condyle.

The clinical features of a mandibular condylar fracture include:

- preauricular pain and tenderness

- difficulty opening the mouth

- with a unilateral fracture, jaw deviates to affected side on attempted opening

- with a bilateral fracture there is typically an anterior open bite

- radiologic findings of fracture of one or both condylar process(es).

Entitlement considerations

Section A: Causes and/or aggravation of temporomandibular joint conditions

For VAC entitlement purposes, the following factors are accepted to cause or aggravate temporomandibular joint conditions, and may be considered along with the evidence to assist in establishing a relationship to service. The factors have been determined based on a review of up-to-date scientific, medical, and dental literature, as well as evidence-based medical and dental best practices. Factors other than those listed may be considered, however consultation with a disability consultant or dental advisor is recommended.

The timelines cited below are for guidance purposes. Each case should be adjudicated on the evidence provided and its own merits.

Factors

- Having experienced direct trauma:

- to the mandible (chin) at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of the TMJ arthralgia or the TMJ disc displacement. Examples include:

- sports injury

- fall

- assault

- motor vehicle accident (MVA).

- to the TMJ(s) prior to the clinical onset or aggravation of the TMJOA, including:

- mandibular fracture

- condylar fracture

- direct blow to the mandible (chin).

- involving pulling the mandible forward with complete or partial dislocation at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of the TMJ hypermobility. Examples include:

- combat mouth restraint

- traumatic rupture of ligaments.

- to the mandible (chin) at the time of clinical onset of a condylar fracture. Examples include:

- individual falling on an object, typically the ground, with contact on the lower anterior border of the mandible (for example, fainting)

- direct blow to the mandible (for example, assault, sports)

- combination of forces (blow, fall) as found in MVA which can result in more severe injuries.

- to the mandible (chin) at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of the TMJ arthralgia or the TMJ disc displacement. Examples include:

- Having a mandibular fracture at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of the TMJ arthralgia, TMJ disc displacement or hypermobility disorder, or TMJOA.

- Experiencing excessive mouth opening, specifically:

- wide or prolonged mouth opening at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of the TMJ arthralgia or TMJ disc displacement. Examples include:

- dental procedure (for example, third molar extraction)

- long dental appointment

- oral intubation during general anesthesia

- transoral bronchoscopy

- yawning

- biting into an apple.

- forceful or extreme mouth opening (hyperextension) event at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of the TMJ arthralgia or TMJ hypermobility. Examples include:

- yawning

- vomiting

- abnormal chewing

- oral intubation during general anesthesia

- transoral bronchoscopy.

- wide or prolonged mouth opening at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of the TMJ arthralgia or TMJ disc displacement. Examples include:

- Having a malocclusion(s) which requires overstretching on opening at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of the TMJ disc displacement or hypermobility disorder. Examples include:

- deep bite malocclusion (overbite greater 40%)

- steep slope of the articular eminence

- asymmetric or damaged condyles.

- Exhibiting a chronic oral behaviour as a symptom of a diagnosed clinically significant psychiatric condition:

- that increases pressure on the TMJ prior to clinical onset or aggravation of the TMJ arthralgia, as supported by the treating dentist or dentist specialist.

- over an extended period of time that is not controlled with treatment, increasing pressure on the TMJ(s), aggravating an existing TMJ disc displacement or hypermobility disorder, as supported by the treating dentist or dentist specialist.

Note: At the time of the publication of this EEG, the health-related expert opinion and scientific evidence indicates:

- a chronic oral behaviour as a symptom of a diagnosed clinically significant psychiatric condition is only an aggravating factor, not a causal factor for a TMJ disc displacement or hypermobility disorder.

- signs and symptoms associated with a diagnosed clinically significant psychiatric condition, other than the chronic oral behaviours listed above for TMJ disc displacement and hypermobility disorders, are not causal or aggravating factors for TMJ conditions.

- Having chronic persistent bruxism over an extended period of time that is not controlled with treatment:

- prior to the clinical onset or aggravation of the TMJ arthralgia.

- increasing pressure on the TMJ(s), aggravating an existing TMJ disc displacement or hypermobility disorder.

Note: At the time of the publication of this EEG, the health-related expert opinion and scientific evidence indicates chronic bruxism is only an aggravating factor, not a causal factor, for TMJ disc displacement and hypermobility disorders.

- Having generalized joint laxity or loss of elasticity at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of the TMJ disc displacement or hypermobility disorder. Examples include but are not limited to:

- connective tissue disorders (for example, scleroderma)

- autoimmune diseases (for example, mixed connective tissue disease).

- Having developmental or structural abnormalities, such as a flat articular eminence and/or shallow glenoid fossa, at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of the TMJ hypermobility disorder.

- Having chronic synovial inflammation due to a history of:

- TMJ disc displacement without reduction prior to the clinical onset or aggravation of the TMJOA

- repeated TMJ subluxation and/or luxation events prior to the clinical onset or aggravation of the TMJOA.

- Having a surgical TMJ discectomy prior to the clinical onset or aggravation of the TMJOA.

- Having an autoimmune disease prior to the clinical onset or aggravation of the TMJ arthralgia. Examples include:

- rheumatoid arthritis

- psoriatic arthritis

- juvenile idiopathic condylar resorption

- scleroderma

- mixed connective tissue disease.

- Inability to obtain appropriate clinical management of the TMJ condition.

Note: Section B and Section C are the same for all TMDs and can be found under Entitlement considerations below.

Entitlement considerations

In this section

- Section A: Causes and/or aggravation

- Section B: Medical or dental conditions which are to be included in entitlement/assessment of any temporomandibular disorder

- Section C: Common medical or dental conditions which may result, in whole or in part, from temporomandibular disorders and/or their treatment

Section A: Causes and/or aggravation

This EEG includes Section A for masticatory muscle conditions and another Section A for temporomandibular joint conditions. Each section can be found separately above.

Section B: Medical or dental conditions which are to be included in entitlement/assessment of any temporomandibular disorder

Section B provides a list of diagnosed conditions which are considered for VAC purposes to be included in the entitlement and assessment of TMDs.

- Myalgia of the muscles of mastication

- Local myalgia of the muscles of mastication

- Myofascial pain of the muscles of mastication

- Myofascial pain of the muscles of mastication with referral

- Temporomandibular joint arthralgia

- Temporomandibular joint arthritis

- Temporomandibular joint disc displacement with reduction

- Temporomandibular joint disc displacement with reduction with intermittent locking

- Temporomandibular joint disc displacement without reduction

- Temporomandibular joint subluxation

- Temporomandibular joint luxation

- Temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis/osteoarthrosis

- Closed fracture of condylar process

- Closed fracture of subcondylar process

- Open fracture of condylar process

- Open fracture of subcondylar process

Section C: Common medical or dental conditions which may result, in whole or in part, from temporomandibular disorders and/or their treatment

No consequential medical or dental conditions were identified at the time of the publication of this EEG. If the merits of the case and medical evidence indicate that a possible consequential relationship may exist, consultation with a disability consultant or dental advisor is recommended.

Links

Related VAC guidance and policy:

- Adjustment Disorder – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Anxiety Disorders – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Bipolar and Related Disorders – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Bruxism – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Depressive Disorders – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Feeding and Eating Disorders – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Rheumatoid Arthritis – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Schizophrenia – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Substance Use Disorders – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Pain and Suffering Compensation – Policies

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police Disability Pension Claims – Policies

- Dual Entitlement – Disability Benefits – Policies

- Establishing the Existence of a Disability – Policies

- Disability Benefits in Respect of Peacetime Military Service – The Compensation Principle – Policies

- Disability Benefits in Respect of Wartime and Special Duty Service – The Insurance Principle – Policies

- Disability Resulting from a Non-Service Related Injury or Disease – Policies

- Consequential Disability – Policies

- Benefit of Doubt – Policies

References as of 15 April 2025

Ahmad, M., & Schiffman, E. L. (2016). Temporomandibular Joint Disorders and Orofacial Pain. Dental Clinics of North America, 60(1), 105–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cden.2015.08.004

Alhammadi, M. S. (2023). Dimensional and Positional Characteristics of the Temporomandibular Joint of Skeletal Class II Malocclusion with and without Temporomandibular Disorders. The Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice, 23(12), 1203–1210. https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10024-3441

Australian Government Repatriation Medical Authority. (2021) Statement of Principles concerning temporomandibular disorder (Balance of Probabilities) (No. 43 of 2021). SOPs - Repatriation Medical Authority

Australian Government Repatriation Medical Authority. (2021) Statement of Principles concerning temporomandibular disorder (Reasonable Hypothesis) (No. 42 of 2020). SOPs - Repatriation Medical Authority

Ayouni, I., Chebbi, R., Hela, Z., & Dhidah, M. (2019).Comorbidity between fibromyalgia and temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology and oral radiology, 128(1), 33–42. PMID: 30981530.

Bethea, A., Kleykamp, B.A., Ferguson, M.C., McNicol, E., Bixho, I., Arnold, L.M., Edwards, R.R., Fillingim, R., Grol-Prokopczyk, H., Ohrbach, R., Turk, D.C., & Dworkin, R.H. (2022). The prevalence of comorbid chronic pain conditions among patients with temporomandibular disorders: A systematic review. JADA, (153)3, 241-250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2021.08.008

Bueno, C. H., Pereira, D. D., Pattussi, M. P., Grossi, P. K., & Grossi, M. L. (2018).Gender differences in temporomandibular disorders in adult populational studies: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 45(9), 720–729. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12661

Castrillon, E. E., & Exposto, F. G. (2018). Sleep Bruxism and Pain. Dental Clinics of North America, 62(4), 657–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cden.2018.06.003

Cioffi, I., Landino, D., Donnarumma, V., Castroflorio, T., Lobbezoo, F., & Michelotti, A. (2017). Frequency of daytime tooth clenching episodes in individuals affected by masticatory muscle pain and pain-free controls during standardized ability tasks. Clinical Oral Investigations, 21(4), 1139–1148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-016-1870-8

Committee on Temporomandibular Disorders (TMDs): From Research Discoveries to Clinical Treatment, Board on Health Sciences Policy, Board on Health Care Services, Health and Medicine Division, & National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2020). Temporomandibular Disorders: Priorities for Research and Care (E. C. Bond, S. Mackey, R. English, C. T. Liverman, & O. Yost, Eds.; p. 25652). National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25652

Dworkin, R. H., Bruehl, S., Fillingim, R. B., Loeser, J. D., Terman, G. W., & Turk, D. C. (2016). Multidimensional Diagnostic Criteria for Chronic Pain: Introduction to the ACTTION-American Pain Society Pain Taxonomy (AAPT). The Journal of Pain, 17(9 Suppl), T1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2016.02.010

Hugon-Rodin, J., Lebègue, G., Becourt, S. et al. Gynecologic symptoms and the influence on reproductive life in 386 women with hypermobility type ehlers-danlos syndrome: a cohort study. (2016). Orphanet J Rare Dis (11)124. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-016-0511-2

Johansson, A., Unell, L., Carlsson, G. E., Söderfeldt, B., & Halling, A. (2003). Gender difference in symptoms related to temporomandibular disorders in a population of 50-year-old subjects. Journal of Orofacial Pain, 17(1), 29–35.

Klasser, G. D., Almoznino, G., & Fortuna, G. (2018). Sleep and Orofacial Pain. Dental Clinics of North America, 62(4), 629–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cden.2018.06.005

Klasser, G. D., Lau, J., Tiwari, L., & Balasubramaniam, R. (2020). Masticatory muscle pain: Diagnostic considerations, pathophysiologic theories and future directions. Frontiers of Oral and Maxillofacial Medicine, 2, 14–14. https://doi.org/10.21037/fomm-20-33

Kumar, R., Pallagatti, S., Sheikh, S., Mittal, A., Gupta, D., & Gupta, S. (2015). Correlation Between Clinical Findings of Temporomandibular Disorders and MRI Characteristics of Disc Displacement. The Open Dentistry Journal, 9, 273–281. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874210601509010273

La Touche, R., Paris-Alemany, A., Hidalgo-Pérez, A., López-de-Uralde-Villanueva, I., Angulo-Diaz-Parreño, S., & Muñoz-García, D. (2018). Evidence for Central Sensitization in Patients with Temporomandibular Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies. Pain Practice: The Official Journal of World Institute of Pain, 18(3), 388–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/papr.12604

Leeuw, R. de, & Klasser, G. D. (Eds.). (2018). Orofacial pain: Guidelines for assessment, diagnosis, and management (Sixth edition). Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc.

Maixner, W., Diatchenko, L., Dubner, R., Fillingim, R. B., Greenspan, J. D., Knott, C., Ohrbach, R., Weir, B., & Slade, G. D. (2011). Orofacial pain prospective evaluation and risk assessment study—The OPPERA study. The Journal of Pain, 12(11 Suppl), T4-11.e1-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2011.08.002

Manfredini, D., & Lobbezoo, F. (2021). Sleep bruxism and temporomandibular disorders: A scoping review of the literature. Journal of Dentistry, 111, 103711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2021.103711

Minervini, G., Franco, R., Marrapodi, M. M., Fiorillo, L., Cervino, G., & Cicciù, M. (2023). Post‐traumatic stress, prevalence of temporomandibular disorders in war veterans: Systematic review with meta‐analysis. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 50(10), 1101–1109. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.13535

Minervini, G., D'Amico, C., Cicciù, M., & Fiorillo, L. (2023). Temporomandibular Joint Disk Displacement: Etiology, Diagnosis, Imaging, and Therapeutic Approaches. The Journal of craniofacial surgery, 34(3), 1115–1121. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000009103

Moreno‐Hay, I., & Bender, S. D. (2024). Bruxism and oro‐facial pain not related to temporomandibular disorder conditions: Comorbidities or risk factors? Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 51(1), 196–201. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.13581

Mortazavi, N., Tabatabaei, A. H., Mohammadi, M., & Rajabi, A. (2023). Is bruxism associated with temporomandibular joint disorders? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Evidence-Based Dentistry, 24(3), 144. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41432-023-00911-6

Mottaghi, A., & Zamani, E. (2014). Temporomandibular joint health status in war veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of education and health promotion, 3, 60. https://doi.org/10.4103/2277-9531.134765

National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. (2018). Prevalence of TMJD and its Signs and Symptoms. National Institute of Health. https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/research/data-statistics/facial-pain/prevalence

Nykänen, L., Manfredini, D., Lobbezoo, F., Kämppi, A., Bracci, A., & Ahlberg, J. (2024). Assessment of awake bruxism by a novel bruxism screener and ecological momentary assessment among patients with masticatory muscle myalgia and healthy controls. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 51(1), 162–169. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.13462

Okeson, J. P. (2020). Management of temporomandibular disorders and occlusion (Eighth edition). Elsevier.

Ottersen, M. K., Larheim, T. A., Hove, L. H., & Arvidsson, L. Z. (2023). Imaging signs of temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis in an urban population of 65-year-olds: A cone beam computed tomography study. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 50(11), 1194–1201. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.13547

Poluha, R. L., Canales, G. D. la T., Bonjardim, L. R., & Conti, P. C. R. (2021a). Oral behaviors, bruxism, malocclusion and painful temporomandibular joint clicking: Is there an association? Brazilian Oral Research, 35, e090. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-3107bor-2021.vol35.0090

Ramanan, D., Palla, S., Bennani, H., Polonowita, A., & Farella, M. (2021). Oral behaviours and wake-time masseter activity in patients with masticatory muscle pain. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 48(9), 979–988. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.13219

Salinas Fredricson, A., Krüger Weiner, C., Adami, J., Rosén, A., Lund, B., Hedenberg-Magnusson, B., Fredriksson, L., & Naimi-Akbar, A. (2022). The Role of Mental Health and Behavioral Disorders in the Development of Temporomandibular Disorder: A SWEREG-TMD Nationwide Case-Control Study. Journal of Pain Research, Volume 15, 2641–2655. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S381333

Schiffman, E., Ohrbach, R., Truelove, E., Look, J., Anderson, G., Goulet, J.-P., List, T., Svensson, P., Gonzalez, Y., Lobbezoo, F., Michelotti, A., Brooks, S. L., Ceusters, W., Drangsholt, M., Ettlin, D., Gaul, C., Goldberg, L. J., Haythornthwaite, J. A., Hollender, L., … Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group, International Association for the Study of Pain. (2014). Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: Recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network* and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group†. Journal of Oral & Facial Pain and Headache, 28(1), 6–27. https://doi.org/10.11607/jop.1151

Shaefer, J. R., Riley, C. J., Caruso, P., & Keith, D. (2012). Analysis of Criteria for MRI Diagnosis of TMJ Disc Displacement and Arthralgia. International Journal of Dentistry, 2012, 283163. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/283163

Tarhio, R., Toivari, M., Snäll, J., & Uittamo, J. (2023). Causes and treatment of temporomandibular luxation-a retrospective analysis of 260 patients. Clinical Oral Investigations, 27(7), 3991–3997. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-023-05024-z

Thomas, D. C., & Singer, S. R. (2023). Temporomandibular Disorders: The Current Perspective. Dental Clinics of North America, 67(2), i. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0011-8532(23)00008-3

van Selms, M. K., Visscher, C. M., Knibbe, W., Thymi, M., & Lobbezoo, F. (2020). The Association Between Self-Reported Awake Oral Behaviors and Orofacial Pain Depends on the Belief of Patients That These Behaviors Are Harmful to the Jaw. Journal of Oral & Facial Pain and Headache, 34(3), 273–280. https://doi.org/10.11607/ofph.2629

Veterans Affairs Canada (2024). Temporomandibular Joint Anatomy. License purchased for use from TMJ Disorder Vector Illustration. Labeled Jaw Condition Educational Scheme. Diagram With Joint Clicking And Pain Anatomical Structure And Explanation. TMJD Syndrome With Mandibular Movement Closeup. Royalty Free SVG, Cliparts, Vectors, and Stock Illustration. Image 145986196. (123rf.com)

Veterans Affairs Canada (2024). Masticatory Muscles. License purchased for use from Masticatory Muscles And Cheek Bones Muscular System Anatomy Outline Diagram Royalty Free SVG, Cliparts, Vectors, and Stock Illustration. Image 189719639. (123rf.com)

Wilkie, G., & Al-Ani, Z. (2022). Temporomandibular joint anatomy, function and clinical relevance. British Dental Journal, 233(7), 539–546. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-022-5082-0

Willich, L., Bohner, L., Köppe, J., Jackowski, J., Hanisch, M., & Oelerich, O. (2023). Prevalence and quality of temporomandibular disorders, chronic pain and psychological distress in patients with classical and hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: an exploratory study. Orphanet journal of rare diseases, 18(1), 294. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-023-02877-1

World Health Organization. (2022). ICD-11: International classification of diseases (11th revision). https://icd.who.int/

Yi, W.-J., Zhang, J.-Y., Kong, W., Mai, A.-D., & Duan, J.-H. (2023). Clinical research on the relationship between the curve of Wilson and temporomandibular joint disorders. Journal of Stomatology, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 124(5), 101496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jormas.2023.101496