Entitlement Eligibility Guideline (EEG)

Date reviewed: 28 August 2025

Date created: 31 March 2025

ICD-11 codes: BA8Z; BA8Y; BA40-43, 4Z, BA50-52, BA5Y, BA5Z, BA6Z, BA82, BA85, BA86

VAC medical code: 00708 Ischemic heart disease, coronary artery disease, arteriosclerotic heart disease, angina, coronary thrombosis, myocardial infarction

This publication is available upon request in alternate formats.

Full document – PDF Version

Definition

Ischemic heart disease (IHD) is a condition in which the supply of blood and oxygen to the heart tissue is inadequate to meet demand. IHD exists on a spectrum ranging from stable angina to acute coronary syndromes, myocardial infarction, and sudden cardiac death. Common to all conditions across this spectrum is the concept of a supply-demand mismatch.

For the purposes of this entitlement eligibility guideline (EEG), the following conditions are included:

- ischemic heart disease (IHD)

- coronary artery disease (CAD)

- angina, including Prinzmetal angina and unstable angina

- non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI)

- ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)

- myocardial infarction (MI)

- acute coronary syndrome (ACS)

- spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD)

- ischemia with non-obstructive coronary artery disease (INOCA).

Diagnostic standard

A diagnosis from a qualified physiciannurse practitioner (within scope of practice) is required. Documentation should be as comprehensive as possible, including specialist and/or cardiology reports and accompanying cardiac investigations.

The diagnosis of IHD can be made with a high degree of confidence from history and physical examination, and additional investigations such as bloodwork (including cardiac markers such as troponin), electrocardiogram (ECG), exercise stress testing, echocardiogram, and invasive coronary angiography.

Exercise stress testing is a widely used initial test for the diagnosis and estimation of risk and prognosis of IHD. The exercise stress test involves a 12-lead ECG before, during, and after observed exercise, which is usually performed on a treadmill. This test involves monitoring symptoms using ECG, heart rate, and arm blood pressure readings while sustaining a standardized incremental increase in workload while exercising.

An intravenous drug challenge known as stress myocardial perfusion imaging is used to diagnose IHD in individuals who are unable to exercise. Echocardiography may be completed which involves ultrasound examination of the heart to assess valve function, wall motion, blood flow, and pump efficiency.

Coronary arteriography, also called cardiac angiography or cardiac catheterization, involves the placement of a catheter into an artery in the groin or wrist and an injection of contrast dye to allow visualization of the blood vessels of the heart. Cardiac angiography is a valuable tool for diagnosing IHD and determining the best course of treatment such as medication, angioplasty, or bypass surgery.

Anatomy and physiology

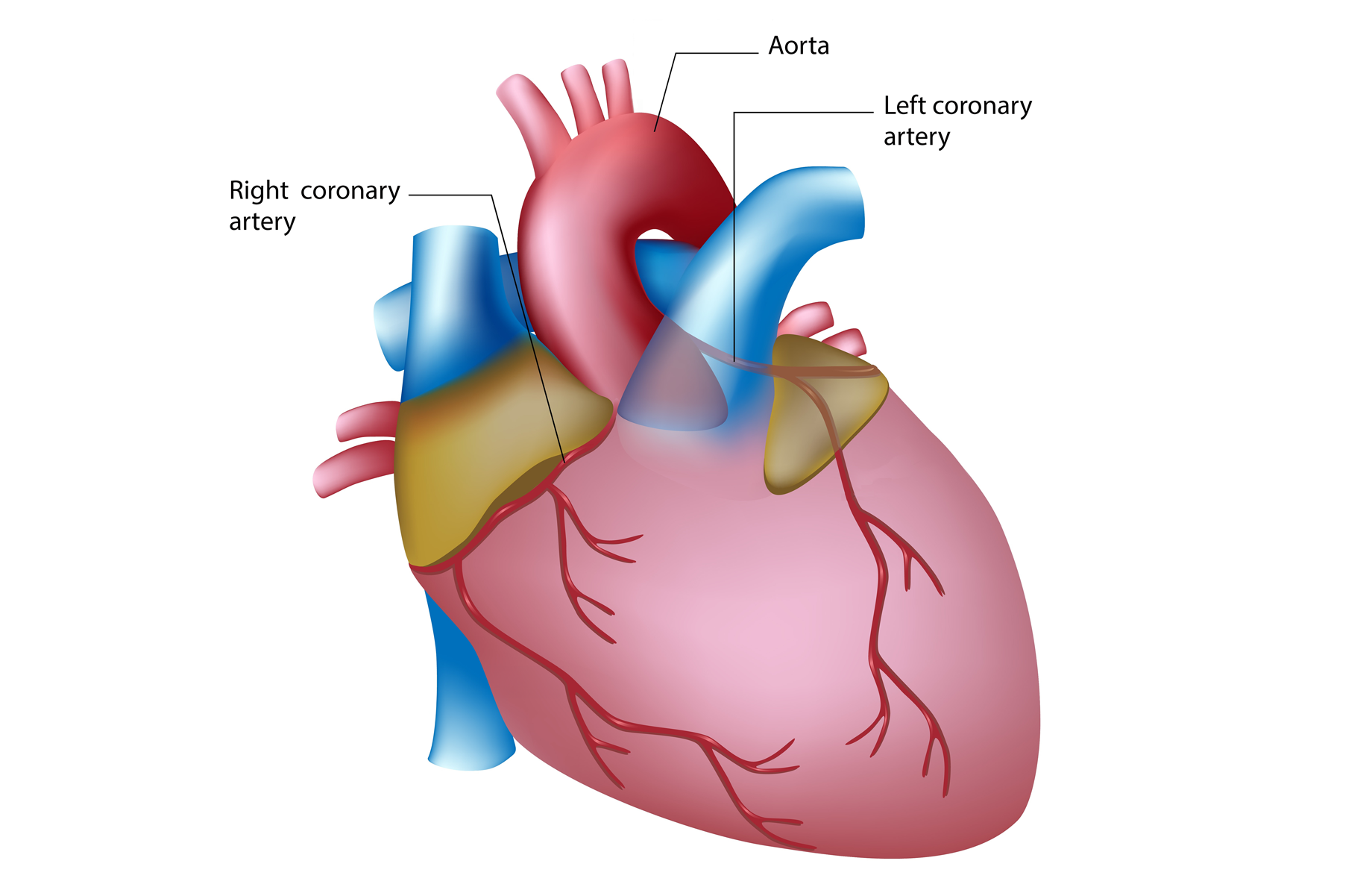

In a healthy heart (Figure 1: Arterial supply of the heart), the coronary arteries branch off the aorta, which is the main artery of the body to supply oxygen-rich blood to different areas of the heart. Under normal conditions, the arteries allow the blood to flow unobstructed. The inner layer of the artery, called the endothelium, is normally smooth to help blood flow easily and prevent blood from sticking or clotting. The myocardium is the muscular middle layer of the heart which is responsible for the pumping action necessary to maintain circulation. An adequate supply of oxygen to the myocardium is dependent on both the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood and sufficient blood flow through the coronary arteries.

Figure 1: Arterial supply of the heart

Illustration of a human heart highlighting the aorta—the main artery that carries oxygen-rich blood to the heart, supplying it with the oxygen and nutrients it needs to function. Branching from the aorta, the left and right coronary arteries. Source: Veterans Affairs Canada (2024).

Ischemia develops when the perfusion of oxygen to the myocardium cannot meet the demand for oxygen. The blood vessels supplying blood to the heart can become narrowed or blocked, referred to as atherosclerosis. Fatty deposits (plaque) build up in the coronary arteries that feed the heart tissue and this accumulation causes narrowing within the coronary arteries, reducing the flow of oxygen-rich blood to the heart.

Atherosclerosis results from an inflammatory and immunologically driven response of the arterial wall to multifactorial and repetitive injury. Complications of atherosclerosis result from progressive growth of plaques and secondary changes in the plaques that can lead to narrowing of the blood vessel (luminal stenosis), thrombosis, embolization, aneurysm formation, and vessel rupture. Progression of atherosclerosis can be influenced by a broad range of metabolic, immunological, and inflammatory factors.

Multiple risk factors are implicated in the development of atherosclerosis including ageing, dyslipidaemia, hypertension, cigarette smoking, and diabetes mellitus. An inflammatory cascade ensues that plays an important role in erosion or rupture of vulnerable plaques leading to atherosclerosis complications which can progress slowly or rapidly depending on the presence of risk factors.

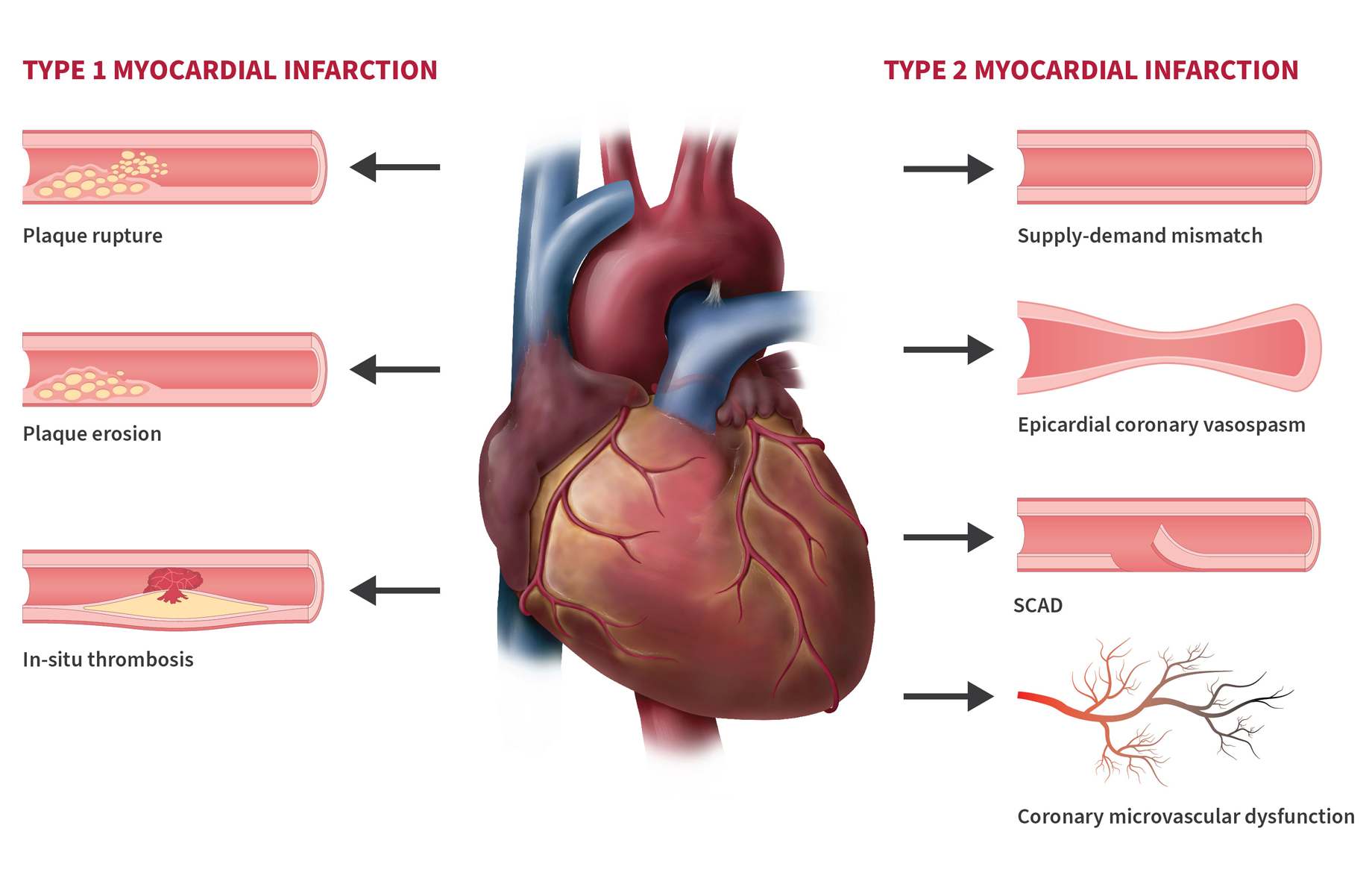

Angina develops when the heart tissue does not receive adequate perfusion of oxygen-rich blood. Angina is a type of chest pain or discomfort associated with IHD. While obstruction of the blood flow through the coronary arteries caused by atherosclerosis is the most common cause, symptoms of angina can occur without evidence of significant obstructive disease. Ischemia with non-obstructive coronary artery disease (INOCA) is a condition where a person experiences symptoms of reduced blood flow to the heart (ischemia), such as chest pain or discomfort (angina), without evidence of narrowing or blockage in the heart vessels (Figure 2: Causes of ischemic heart disease).

Figure 2: Causes of ischemic heart disease

Illustration of Type 1 and Type 2 myocardial infarctions (MI), commonly known as a heart attack. Type 1 infarctions happen due to plaque rupture, plaque erosion or thrombosis. Type 2 infractions are caused by a supply-demand mismatch of oxygen to the heart muscle, often due to epicardial coronary vasospasm, a tear in the blood vessel known as spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) or coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD). Source: From A Guide to Your MINOCA [Figure 2], by University of Ottawa Heart Institute (2024), A Guide to Your MINOCA | University of Ottawa Heart Institute. Copyright 2024 by University of Ottawa Heart Institute. Reprinted with permission.

In INOCA, although the main coronary arteries appear normal or have only mild blockages, there may still be underlying issues affecting blood flow to the heart. These underlying issues may include dysfunction in the small blood vessels (microvascular dysfunction), abnormalities in the lining of the blood vessels (endothelial dysfunction), or spasms in the coronary arteries (coronary artery vasospasm). The pathophysiology behind INOCA is believed to be multifactorial with coronary microvascular dysfunction and/or coronary vasospasm thought to be present in a majority of INOCA cases.

Coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD) is a condition that affects the tiny blood vessels (micro-vessels) in the heart, specifically in the smaller coronary arteries which play a crucial role in delivering oxygen-rich blood to the myocardium. People with CMD experience typical anginal symptoms with evidence of ischemia, though they are not noted to have significant obstruction on further assessment of their coronary arteries.

An infrequent cause of acute MI is spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD). SCAD occurs when there is a sudden split or tear in the wall of one of the coronary arteries without any obvious reason. This split or tear is often referred to as a dissection and can create a false passageway in the blood vessel compromising blood flow to the heart resulting in ischemia or infarction. SCAD predominantly affects females under the age of 50.

Please consult Table 1: Ischemic heart syndromes for coronary syndromes categorized into chronic versus acute.

| Chronic coronary syndrome | Acute coronary syndrome | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stable Angina | NSTEMI | STEMI | SCD | Unstable angina |

|

|

|

|

|

Note: AMI: Acute myocardial infarction, CAD: coronary artery disease, CMD: coronary microvascular dysfunction, IC: intracoronary, NSTEMI: non ST-elevation myocardial infarction, SCD: sudden cardiac death, STEMI: ST-Elevation myocardial infarction. (Adapted from Concistre, G., 2023).

During episodes of inadequate perfusion, the mechanical, biochemical, and electrical functions of the heart tissue are disturbed. Ischemia causes characteristic changes on an ECG and the pumping function of the heart can become impaired. Cardiac troponin is a group of proteins found in heart muscle cells that play a crucial role in regulating contraction of the heart muscle. When heart muscle cells are damaged during reduced blood flow or ischemia, troponin is released into the blood stream making it an important biomarker for detecting myocardial ischemia.

Risk factors for IHD can be classified into modifiable and non-modifiable.

Non-modifiable risk factors include, but are not limited to:

- age

- biological sex

- genetic vulnerability

- family history

- ethnicity.

IHD is more prevalent in older age groups, males, Black, Hispanic, Latino, and Southeast Asian ethnicities, and those with a family history of IHD—particularly if cardiac disease is present in family members younger than 50 years of age. Young and middle-aged females with MI have poorer morbidity, mortality, and quality of life relative to comparable males, which is unexplained by traditional risk factors, comorbidities, and treatments.

Modifiable risk factors also have a significant role in the development of IHD and include aspects related to lifestyle or health that can be changed or controlled to reduce the risk of developing IHD.

Known modifiable risk factors include, but are not limited to:

- smoking

- diet

- physical activity

- obesity

- stress

- hypertension, including hypertensive disorders of pregnancy

- dyslipidemia

- diabetes.

In addition to known risk factors, there are several emerging risk factors for IHD under investigation, including inflammation, air pollution, and sleep disorders. For claims related to emerging risk factors of IHD, consultation with a disability consultant and/or medical advisor is recommended.

Clinical features

The clinical presentation of myocardial ischemia is most often acute chest discomfort. Angina pectoris, or angina for short, is the term used when chest discomfort is thought to be caused by myocardial ischemia. In individuals with myocardial ischemia, chest discomfort is often, but not always, present. Other associated symptoms with ischemia may be present, such as exertional shortness of breath, nausea, sweating, and fatigue. These symptoms have been called anginal equivalents.

The typical presentation of angina is a male over 50 or a female over 60 who reports episodic chest discomfort, usually described as heaviness, pressure, squeezing, smothering, or choking and rarely as frank pain. When asked to identify the location, the individual often places a hand over the sternum, sometimes with a clenched fist to indicate a squeezing, central, substernal discomfort. Angina typically lasts two to five minutes and can radiate to either shoulder or to both arms. Angina can also arise in or radiate to the back, shoulder blade region, base of the neck, jaw, teeth, or epigastrium.

Angina is often triggered by activities and situations that increase myocardial oxygen demand. These activities or situations may include physical activity, cold, emotional stress, sexual intercourse, meals, or laying down which results in an increase in blood return to the heart and increased stress to the heart walls. Typical angina is often relieved with discontinuation of the triggering factor.

The term acute coronary syndrome (ACS) includes acute myocardial infarction, ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-ST elevation myocardial Infarction (NSTEMI), and unstable angina. MI is commonly called a heart attack.

While chest pain is the most common symptom of ACS, other symptoms of ischemia may be present. Chest pain is not required for the diagnosis of ACS. Many people with ACS present with symptoms such as dyspnea or malaise, either alone or in addition to chest pain. Females are more likely to have associated dyspnea than males, and individuals who are older or have diabetes are more likely to present with dyspnea without chest pain. Pain from myocardial ischemia is more often characterized as non-focal chest discomfort or pressure rather than pain, is generally gradual in onset, and is exacerbated by activity. Discomfort that radiates, particularly to arms, should increase suspicion for ACS.

The term acute MI is used when there is acute myocardial injury (STEMI or NSTEMI) with clinical evidence of acute myocardial ischemia and with detection of a rise and/or fall of cardiac troponin values. Acute MI is further categorized into types with type one and type two being the most common. A type one MI is caused by atherothrombotic disease of the coronary arteries which is usually triggered by erosion or rupture of the atherosclerotic plaque. A type two MI results from a mismatch between oxygen supply and demand and can include a variety of potential mechanisms, including coronary artery dissection, vasospasm, emboli, microvascular dysfunction, as well as increases in demand with or without underlying CAD.

There are significant differences between females and males in the epidemiology, diagnosis, response to therapy, and prognosis of IHD. The importance of some metabolic, behavioural, and psychosocial risk factors may differ by biological sex.

Males more often experience the classic symptoms of IHD that include chest pain with radiation to the back and arms. Females more often present with atypical symptoms of IHD such as shortness of breath, chest pain at rest, nausea, and back or jaw pain. Symptoms experienced by females are often not readily recognized as diagnostic for IHD. Females present more often than males with signs and symptoms of IHD in the absence of obstructed coronary arteries.

Female Veterans have been shown to have higher rates of cardiovascular disease than their civilian counterparts. Younger females with previous MI have a two-fold likelihood of developing psychological stress induced myocardial ischemia compared to their male counterparts. Among transgender women, estrogen therapy is associated with higher triglyceride levels contributing to increased risk of cardiovascular disease, including MI.

Entitlement considerations

In this section

Section A: Causes and/or aggravation

Section B: Medical conditions which are to be included in entitlement/ assessment

Section A: Causes and/or aggravation

For Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC) entitlement purposes, the following factors are accepted to cause or aggravate the conditions included in the Definition section of this EEG, and may be considered along with the evidence to assist in establishing a relationship to service. The factors have been determined based on a review of up-to-date scientific and medical literature, as well as evidence-based medical best practices. Factors other than those listed may be considered, however consultation with a disability consultant or medical advisor is recommended.

The timelines cited below are for guidance purposes. Each case should be adjudicated on the evidence provided and its own merits.

Factors

- Having a diagnosis of hypertension before the clinical onset or aggravation of IHD.

- Having a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus before the clinical onset or aggravation of IHD.

- Having a diagnosis of dyslipidemia before the clinical onset or aggravation of IHD.

- Having a diagnosis of severe chronic kidney disease before the clinical onset or aggravation of IHD.

Note: Severe chronic kidney disease is defined as having a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of less than 30 mL/minute/1.73m2 for at least three months.

- Having a clinically significant psychiatric condition for at least five years prior to clinical onset or aggravation of IHD.

Note: For VAC purposes, clinically significant means requiring ongoing treatment and clinical management.

- Being treated with a medication from the specified list below at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of IHD. The medications include, but are not limited to, the following:

- antiandrogen therapy with a gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist for at least seven days prior to aggravation or onset

- antipsychotic

- aromatase inhibitor

- bevacizumab

- capecitabine

- docetaxel

- erlotinib

- fluorouracil

- paclitaxel

- sorafenib.

Note:

- Individual medications may belong to a class of medications. The effects of a specific medication may vary from the class. The effects of the specific medication should be considered.

- If it is claimed a medication resulted in the clinical onset or aggravation of IHD, the following must be established:

- The medication was prescribed to treat an entitled condition.

- The individual was receiving the medication at the time of the clinical onset or aggravation of the IHD.

- The current medical literature supports the medication can result in the clinical onset or aggravation of IHD.

- The medication use is long-term, ongoing, and cannot reasonably be replaced with another medication or the medication is known to have enduring effects after discontinuation.

- Having had exposure to tobacco smoke in a confined space. VAC recognizes that exposure to tobacco smoke is a risk factor for the development of IHD. For VAC purposes, entitlement may be considered for second-hand tobacco smoke exposure in a non-tobacco smoker where exposure has been for at least two hours per day, most days, in an enclosed space for at least one year duration at the time of the clinical onset of IHD.

For acute myocardial infarction only:

- Directly experiencing a traumatic event(s) within 24 hours before the clinical onset or aggravation of IHD.

Traumatic events include, but are not limited to:

- exposure to military combat

- threatened or actual physical assault

- threatened or actual sexual trauma

- being kidnapped

- being taken hostage

- being in a terrorist attack

- being tortured

- incarceration as a prisoner of war

- being in a natural or human-made disaster

- being in a severe motor vehicle accident

- killing or injuring a person

- experiencing a sudden, catastrophic medical incident

- experiencing an acute, severe, emotional stressor.

- Undertaking strenuous physical exertion within an hour of clinical onset or aggravation of IHD.

Note: For VAC purposes, strenuous physical exertion means eight or more METs, and examples include running (approx. 8 km/hr), climbing hills with more than a 10kg load, and climbing more than one flight of stairs at a fast pace.

- Inability to obtain appropriate clinical management of IHD.

Section B: Medical conditions which are to be included in entitlement/assessment

Section B provides a list of diagnosed medical conditions which are considered for VAC purposes to be included in the entitlement and assessment of IHD.

- Coronary artery disease (CAD)

- Angina, including Prinzmetal angina and unstable angina

- Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI)

- ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)

- Myocardial infarction (MI)

- Acute coronary syndrome (ACS)

- Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD)

- Ischemia with non-obstructive coronary artery disease (INOCA)

- Congestive heart failure (CHF)

- Cardiac arrhythmias, including, but not limited to:

- Atrial fibrillation

- Atrial flutter

- Heart block

- Ventricular tachycardia

- Ventricular fibrillation

- Post infarction pericarditis

Section C: Common medical conditions which may result, in whole or in part, from ischemic heart disease and/or its treatment

No consequential medical conditions were identified at the time of the publication of this EEG. If the merits of the case and medical evidence indicate that a possible consequential relationship may exist, consultation with a disability consultant or medical advisor is recommended.

Links

Related VAC guidance and policy:

- Adjustment Disorder – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Anxiety Disorders – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Bipolar and Related Disorders – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Depressive Disorders – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Feeding and Eating Disorders – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Hypertension – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Schizophrenia – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Substance Use Disorders – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Pain and Suffering Compensation – Policies

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police Disability Pension Claims – Policies

- Dual Entitlement – Disability Benefits – Policies

- Establishing the Existence of a Disability – Policies

- Disability Benefits in Respect of Peacetime Military Service – The Compensation Principle – Policies

- Disability Benefits in Respect of Wartime and Special Duty Service – The Insurance Principle – Policies

- Disability Resulting from a Non-Service Related Injury or Disease – Policies

- Consequential Disability – Policies

- Benefit of Doubt – Policies

References as of 31 March 2025

Abrignani, M. G., Lombardo, A., Braschi, A., Renda, N., & Abrignani, V. (2022). Climatic influences on cardiovascular diseases. World journal of cardiology, 14(3), 152.

Ahmed, S. T., Li, R., Richardson, P., Ghosh, S., Steele, L., White, D. L., Djotsa, A. N., Sims, K., Gifford, E., Hauser, E. R., Virani, S. S., Morgan, R., Delclos, G., & Helmer, D. A. (2023). Association of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease, Hypertension, Diabetes, and Hyperlipidemia With Gulf War Illness Among Gulf War Veterans. Journal of the American Heart Association, 12(19), e029575. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.123.029575

Albert CM, Mittleman MA, Chae CU, et al (2000). Triggering of sudden death from cardiac causes by vigorous exertion. N Engl J Med, 343(19): 1355-61.

Albertsen, P. C., Klotz, L., Tombal, B., Grady, J., Olesen, T. K., & Nilsson, J. (2014). Cardiovascular morbidity associated with gonadotropin releasing hormone agonists and an antagonist. European urology, 65(3), 565-573.

Alexeeff, S. E., Liao, N. S., Liu, X., Van Den Eeden, S. K., & Sidney, S. (2021). Long‐term PM2. 5 exposure and risks of Ischemic Heart Disease and stroke events: review and meta‐analysis. Journal of the American Heart Association, 10(1), e016890.

Allesøe, K., Aadahl, M., Jacobsen, R. K., Kårhus, L. L., Mortensen, O. S., & Korshøj, M. (2023). Prospective relationship between occupational physical activity and risk of ischaemic heart disease: are men and women differently affected?. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, zwad067.

American College of Sports Medicine, Liguori, G., Feito, Y., Fountaine, C., & Roy, B. (Eds.). (2021). ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription (Eleventh edition). Wolters Kluwer.

Aranda, G., Halperin, I., Gomez-Gil, E., Hanzu, F. A., Segui, N., Guillamon, A., & Mora, M. (2021). Cardiovascular risk associated with gender affirming hormone therapy in transgender population. Frontiers in endocrinology, 12, 718200.

Assari S. (2014). Veterans and risk of heart disease in the United States: a cohort with 20 years of follow up. International journal of preventive medicine, 5(6), 703–709.

Athanasiadou, F., Tzotzi, A., Eumorfia, K., Alevizopoulos, G., & Kallergis, G. (2015). Relationship between depression and coronary artery disease risk in healthy Greek Military Population. Balkan Military Medical Review, 18(1).

Australian Government, Repatriation Medical Authority (2021). Statement of Principles concerning ischaemic heart disease (Balance of probabilities)(No. 2 of 2016). SOPs - Repatriation Medical Authority

Australian Government, Repatriation Medical Authority (2021). Statement of Principles concerning ischaemic heart disease (Reasonable Hypothesis)(No. 1 of 2016). SOPs - Repatriation Medical Authority

Backé, E. M., Seidler, A., Latza, U., Rossnagel, K., & Schumann, B. (2012). The role of psychosocial stress at work for the development of cardiovascular diseases: a systematic review. International archives of occupational and environmental health 85, 67-79.

Bailar JC 3rd (1999). Editorial: Passive smoking, coronary heart disease, and meta-analysis. N Engl J Med, 340(12): 958-9.

Bakhshian, K. R., Moshkani, F. M., & Bahrami, A. A. (2012). Risk factor profile and angiography findings in military and non-military patients with coronary artery disease.

Barbosa De Accioly Mattos, M., Bernardo Peixoto, C., Geraldo de Castro Amino, J., Cortes, L., Tura, B., Nunn, M., ... & Sansone, C. (2024). Coronary atherosclerosis and periodontitis have similarities in their clinical presentation. Frontiers in Oral Health, 4, 1324528.

Bell Ngan, W., Essama Eno Belinga, L., Essam Nlo’O, A. S. P., Lemogoum, D., Roche, F., Mandengue, S. H., & Bongue, B. (2019). Cardiovascular disease risk factors of military: A comparative assessment with civilians. European Journal of Public Health, 29(Supplement_4). https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz185.361

Bhatt, D. L., Lopes, R. D., & Harrington, R. A. (2022). Diagnosis and treatment of acute coronary syndromes: a review. Jama, 327(7), 662-675.

Boice Jr, J. D., Quinn, B., Al-Nabulsi, I., Ansari, A., Blake, P. K., Blattnig, S. R., ... & Dauer, L. T. (2022). A million persons, a million dreams: a vision for a national center of radiation epidemiology and biology. International journal of radiation biology, 98(4), 795-821.

Boos, C. J., Schofield, S., Bull, A. M., Fear, N. T., Cullinan, P., & Bennett, A. N. (2023). The relationship between combat-related traumatic amputation and subclinical cardiovascular risk. International Journal of Cardiology, 390, 131227.

Boos, C. J., Schofield, S., Cullinan, P., Dyball, D., Fear, N. T., Bull, A. M., ... & Bennett, A. N. (2022). Association between combat-related traumatic injury and cardiovascular risk. Heart, 108(5), 367-3

Bourdrel T, Bind MA, Béjot Y, Morel O, Argacha JF. Cardiovascular effects of air pollution. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2017; 110: 634–42. 74.

Brook RD, Rajagopalan S, Pope A 3rd, et al (2010). Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: An update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 121(21): 2331-78.

Burke AP, Farb A, Malcom GT, et al (1999). Plaque rupture and sudden death related to exertion in men with coronary artery disease. JAMA, 281(10): 921-6.

Caceres, B. A., Jackman, K. B., Edmondson, D., & Bockting, W. O. (2020). Assessing gender identity differences in cardiovascular disease in US adults: an analysis of data from the 2014–2017 BRFSS. Journal of behavioral medicine, 43, 329-338.

Celermajer, D. S., Adams, M. R., Clarkson, P., Robinson, J., McCredie, R., Donald, A., & Deanfield, J. E. (1996). Passive smoking and impaired endothelium-dependent arterial dilatation in healthy young adults. New England Journal of Medicine, 334(3), 150-155.

Centers for Disease Control (2022). Health Problems caused by secondhand smoke. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/secondhand-smoke/health.html

Cesaroni G, Forastiere F, Stafoggia M, et al (2014). Long term exposure to ambient air pollution and incidence of acute coronary events: prospective cohort study and meta-analysis in 11 European cohorts from the ESCAPE Project. BMJ, 348: f7412.

Chaar, S., Yoon, J., Abdulkarim, J., Villalobos, J., Garcia, J., & Castillo, H. L. (2022). Angina outcomes in secondhand smokers: results from the national health and nutrition examination survey 2007–2018. Avicenna Journal of Medicine, 12(02), 073-080.

Chen, F., Song, Y., Li, W., Xu, H., Dan, H., & Chen, Q. (2024). Association between periodontitis and mortality of patients with cardiovascular diseases: a cohort study based on NHANES. Journal of Periodontology, 95(2), 175-184.

Chen X, Ramanan B, Tsai S, Jeon-Slaughter H. Differential impact of aging on cardiovascular risk in women military service members. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e015087. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.120.015087

Civieri, G., Kerkhof, P. L., Montisci, R., Iliceto, S., & Tona, F. (2023). Sex differences in diagnostic modalities of coronary artery disease: Evidence from coronary microcirculation. Atherosclerosis, 117276.

Clayton, J. A., & Gaugh, M. D. (2022). Sex as a biological variable in cardiovascular diseases: JACC focus seminar 1/7. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 79(14), 1388-1397.

Cocchetti, C., Castellini, G., Iacuaniello, D., Romani, A., Maggi, M., Vignozzi, L., ... & Fisher, A. D. (2021). Does gender-affirming hormonal treatment affect 30-year cardiovascular risk in transgender persons? A two-year prospective European study (ENIGI). The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 18(4), 821-829.

Concistre, G. (2023). Ischemic Heart Disease: From Diagnosis to Treatment (1st ed.). Springer International Publishing AG. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-25879-4

Connelly, P. J., Azizi, Z., Alipour, P., Delles, C., Pilote, L., & Raparelli, V. (2021). The importance of gender to understand sex differences in cardiovascular disease. Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 37(5), 699-710.

Connelly, P. J., Marie Freel, E., Perry, C., Ewan, J., Touyz, R. M., Currie, G., & Delles, C. (2019). Gender-affirming hormone therapy, vascular health and cardiovascular disease in transgender adults. Hypertension, 74(6), 1266-1274.

Cosselman, K. E., Navas-Acien, A., & Kaufman, J. D. (2015). Environmental factors in cardiovascular disease. Nature Reviews Cardiology, 12(11), 627-642.

Crum-Cianflone NF, Bagnell ME, Schaller E, Boyko EJ, Smith B, Maynard C, Ulmer CS, Vernalis M, Smith TC (2014). Impact of combat deployment and posttraumatic stress disorder on newly reported coronary heart disease among US active duty and reserve forces. Circulation. ;129:1813–1820.

Cummings KM, Markello SJ, Mahoney MC, et al (1989). Measurement of lifetime exposure to passive smoke. American journal of epidemiology, 130(1): 22-32.

Cuti, E. C., Dika, Z., Hrsak, L. D., Jelakovic, A., Mikulec, M., Pozgaj, F., Roginic, S., Karaula, N. T., & Jelakovic, B. (2018). High cardiovascular risk in military veterans; cardiovascular health in Croatian veterans project; results of the pilot study. Journal of Hypertension, 36 Suppl 1-ESH 2018 Abstract Book(Supplement 1), e300–e300. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.hjh.0000539875.27540.3d

Davis RM (1997). Passive smoking: history repeats itself: strong public health action is long overdue. BMJ, 315(7114): 961-2.

Dhalla, N. S., & Oštádal, B. (Eds.). (2020). Sex differences in heart disease. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58677-5

Diener, H. C. (2020). The risks or lack thereof of migraine treatments in vascular disease. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 60(3), 649-653.

Dikobo, S. J. E., Lemieux, I., Poirier, P., Després, J. P., & Alméras, N. (2023). Leisure-time physical activity is more strongly associated with cardiometabolic risk than occupational physical activity: Results from a workplace lifestyle modification program. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, 78, 74-82.

Dobson AJ, Alexander HM, Heller RF, et al (1991). Passive Smoking and the risk of heart attack or coronary death. Med J Aust, 154(12): 793-7.

Dockery DW, Stone PH (2007). Cardiovascular risks from fine particulate air pollution. N Engl J Med, 356(5): 511-3.

Dyball, D., Bennett, A. N., Schofield, S., Cullinan, P., Boos, C. J., Bull, A. M., ... & Fear, N. T. (2023). The underlying mechanisms by which PTSD symptoms are associated with cardiovascular health in male UK military personnel: The ADVANCE cohort study. Journal of psychiatric research, 159, 87-96.

Ebrahimi, R., Yano, E. M., Alvarez, C. A., Dennis, P. A., Shroyer, A. L., Beckham, J. C., & Sumner, J. A. (2023). Trends in Cardiovascular Disease Mortality in US Women Veterans vs Civilians. JAMA Network Open, 6(10), e2340242-e2340242.

Eng, A., Denison, H. J., Corbin, M., Barnes, L., Mannetje, A. T., McLean, D., ... & Douwes, J. (2023). Long working hours, sedentary work, noise, night shifts and risk of ischaemic heart disease. Heart, 109(5), 372-379.

Eriksson, H. P., Andersson, E., Schiöler, L., Söderberg, M., Sjöström, M., Rosengren, A., & Torén, K. (2018). Longitudinal study of occupational noise exposure and joint effects with job strain and risk for coronary heart disease and stroke in Swedish men. BMJ open, 8(4).

Fang, S. C., Cassidy, A., & Christiani, D. C. (2010). A systematic review of occupational exposure to particulate matter and cardiovascular disease. International journal of environmental research and public health, 7(4), 1773-1806.

Fenton, W. S., & Stover, E. S. (2006). Mood disorders: Cardiovascular and diabetes comorbidity. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 19(4), 421–427. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.yco.0000228765.33356.9f

Flor, L. S., Anderson, J. A., Ahmad, N., Aravkin, A., Carr, S., Dai, X., ... & Gakidou, E. (2024). Health effects associated with exposure to secondhand smoke: a Burden of Proof study. Nature medicine, 30(1), 149-167.

Franklin, B. A., Thompson, P. D., Al-Zaiti, S. S., Albert, C. M., Hivert, M. F., Levine, B. D., ... & American Heart Association Physical Activity Committee of the Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; and Stroke Council. (2020). Exercise-related acute cardiovascular events and potential deleterious adaptations following long-term exercise training: placing the risks into perspective–an update: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 141(13), e705-e736.

Frayne, S. M., Skinner, K. M., Sullivan, L. M., & Freund, K. M. (2003). Sexual assault while in the military: violence as a predictor of cardiac risk?. Violence and victims, 18(2), 219-225.

Gasparrini, A., Guo, Y., Hashizume, M., Lavigne, E., Tobias, A., Zanobetti, A., ... & Armstrong, B. G. (2016). Changes in susceptibility to heat during the summer: a multicountry analysis. American journal of epidemiology, 183(11), 1027-1036.

Gao, Z., Chen, Z., Sun, A., & Deng, X. (2019). Gender differences in cardiovascular disease. edicine in Novel Technology and Devices, 4, 100025.

Ghanshani, S., Chen, C., Lin, B., Duan, L., Shen, Y. J. A., & Lee, M. S. (2020). Risk of acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and death in migraine patients treated with triptans. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 60(10), 2166-2175.

Gibson, C. J., Maguen, S., Xia, F., Barnes, D. E., Peltz, C. B., & Yaffe, K. (2020). Military sexual trauma in older women veterans: prevalence and comorbidities. Journal of general internal medicine, 35, 207-213.

Giri S, Thompson PD, Kiernan FJ, et al (1999). Clinical and angiographic characteristics of exertion-related acute myocardial infarction. JAMA, 282(18): 1731-6.

Glantz SA, Parmley WW (1995). Clinical cardiology: passive smoking and heart disease: mechanisms and risk. JAMA, 273(13): 1047-53.

Gomez-Acebo, I., Llorca, J., & Dierssen, T. (2013). Cold-related mortality due to cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases and cancer: a case-crossover study. Public Health, 127(3), 252-258.

Guo, Y., Punnasiri, K., & Tong, S. (2012). Effects of temperature on mortality in Chiang Mai city, Thailand: a time series study. Environmental health, 11, 1-9.

Guo, X., Li, X., Liao, C., Feng, X., & He, T. (2023). Periodontal disease and subsequent risk of cardiovascular outcome and all-cause mortality: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Plos one, 18(9), e0290545.

Gustafsson, N., Ahlqvist, J., Näslund, U., Buhlin, K., Gustafsson, A., Kjellström, B., ... & Levring Jäghagen, E. (2020). Associations among periodontitis, calcified carotid artery atheromas, and risk of myocardial infarction. Journal of Dental Research, 99(1), 60-68.

Haider, A., Bengs, S., Luu, J., Osto, E., Siller-Matula, J. M., Muka, T., & Gebhard, C. (2020). Sex and gender in cardiovascular medicine: presentation and outcomes of acute coronary syndrome. European heart journal, 41(13), 1328-1336.

Hallqvist J, Moller J, Ahlbom A, et al (2000). Does heavy physical exertion trigger myocardial infarction? A case-crossover analysis nested in a population-based case-referent study. Am J Epidemiol, 151(5): 459-67.

Han JK, Yano EM, Watson KE, Ebrahimi R. Cardiovascular care in women veterans. Circulation. 2019;139:1102–1109.

Haskell, S. G., Brandt, C., Burg, M., Bastian, L., Driscoll, M., Goulet, J., Mattocks, K., & Dziura, J. (2017). Incident Cardiovascular Risk Factors Among Men and Women Veterans After Return From Deployment. Medical care, 55(11), 948–955. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000801

He J, Vupputuri S, Allen K, et al (1999). Passive smoking and the risk of coronary heart disease - a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. N Engl J Med, 340(12): 920-6.

Heart & Stroke Foundation. (2020). Position Statement: Sex and Gender-Based Analysis and reporting: Ensuring equity in health research (pp. 1 3) [2017 Position Statement]. Heart & Stroke Foundation of Canada. https://www.heartandstroke.ca/-/media/pdf-files/position-statements/sex-and-gender-policy-statement-en.pdf?rev=3c8baf500544481fbf732a007e61b8a5

Henderson, E. R., Boyer, T. L., Wolfe, H. L., & Blosnich, J. R. (2024). Causes of death of transgender and gender diverse veterans. American journal of preventive medicine, 66(4), 664-671.

Hill Se, Blakely TA, Kawachi I, et al (2004). Mortality among "never smokers" living with smokers: two cohort studies, 1981-4 and 1996-9. BMJ, 328(7446): 988-9.

Hinojosa, R. (2020). Cardiovascular disease among United States military veterans: Evidence of a waning healthy soldier effect using the National Health Interview Survey. Chronic Illness, 16(1), 55–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742395318785237

Holtzman, J. N., Kaur, G., Hansen, B., Bushana, N., & Gulati, M. (2023). Sex differences in the management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis, 117268.

Howard, J. T., Janak, J. C., Santos-Lozada, A. R., McEvilla, S., Ansley, S. D., Walker, L. E., Spiro, A., & Stewart, I. J. (2021). Telomere Shortening and Accelerated Aging in US Military Veterans. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1743-. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041743

Huppert, L. A. (2021). Huppert’s Notes: Pathophysiology and Clinical Pearls for Internal Medicine. McGraw-Hill Education LLC.

ILO Encylopaedia: CV System https://www.iloencyclopaedia.org/part-i-47946/cardiovascular-system/physical-chemical-and-biological-hazards

Iversen B, Jacobsen BK, Lochen ML (2013). Active and passive smoking and the risk of myocardial infarction in 24,968 men and women during 11 year of follow-up: the Tromso Study. Eur J Epidemiol, 28(8): 659-67.

Izzy, S., Grashow, R., Radmanesh, F., Chen, P., Taylor, H., Formisano, R., ... & Zafonte, R. (2023). Long-term risk of cardiovascular disease after traumatic brain injury: screening and prevention. The Lancet Neurology, 22(10), 959-970.

Jakubowski, K. P., Murray, V., Stokes, N., & Thurston, R. C. (2021). Sexual violence and cardiovascular disease risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas, 153, 48-60.

Janak, J. C., Pérez, A., Alamgir, H., Orman, J. A., Cooper, S. P., Shuval, K., DeFina, L., Barlow, C. E., & Gabriel, K. P. (2017). U.S. Military Service and the Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome: Findings from a Cross-Sectional Analysis of the Cooper Center Longitudinal Study, 1979–2013. Preventive Medicine, 95, 52–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.11.017

Jeon-Slaughter, H., Chen, X., Tsai, S., Ramanan, B., & Ebrahimi, R. (2021). Developing an Internally Validated Veterans Affairs Women Cardiovascular Disease Risk Score Using Veterans Affairs National Electronic Health Records. Journal of the American Heart Association, 10(5), e019217. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.120.019217

Johnson, A. M., Rose, K. M., Elder Jr, G. H., Chambless, L. E., Kaufman, J. S., & Heiss, G. (2010). Military combat and risk of coronary heart disease and ischemic stroke in aging men: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Annals of epidemiology, 20(2), 143-150.

Katon, J., Mattocks, K., Zephyrin, L., Reiber, G., Yano, E. M., Callegari, L., ... & Haskell, S. (2014). Gestational diabetes and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy among women veterans deployed in service of operations in Afghanistan and Iraq. Journal of women's health, 23(10), 792-800.

Khraishah, H., Alahmad, B., Ostergard Jr, R. L., AlAshqar, A., Albaghdadi, M., Vellanki, N., ... & Rajagopalan, S. (2022). Climate change and cardiovascular disease: implications for global health. Nature Reviews Cardiology, 19(12), 798-812.

Kivimäki, M., Nyberg, S. T., Batty, G. D., Fransson, E. I., Heikkilä, K., Alfredsson, L., ... & Theorell, T. (2012). Job strain as a risk factor for coronary heart disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data. The Lancet, 380(9852), 1491-1497.

Krahn GL, Walker DK, Correa‐DeAraujo R. Persons with disabilities as an unrecognized health disparity population. Am J Public Health. 2015; 105:S198–S206.

Knutsson, A., Åkerstedt, T., & Jonsson, B. G. (1988). Prevalence of risk factors for coronary artery disease among day and shift workers. Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health, 317-321.

Kobayashi, Y., Yamagishi, K., Muraki, I., Kokubo, Y., Saito, I., Yatsuya, H., ... & JPHC Study Group. (2022). Secondhand smoke and the risk of incident cardiovascular disease among never-smoking women. Preventive Medicine, 162, 107145.

Lee, M. T., Mahtta, D., Ramsey, D. J., Liu, J., Misra, A., Nasir, K., ... & Virani, S. S. (2021). Sex-related disparities in cardiovascular health care among patients with premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. JAMA cardiology, 6(7), 782-790.

Leng, Y., Hu, Q., Ling, Q., Yao, X., Liu, M., Chen, J., ... & Dai, Q. (2023). Periodontal disease is associated with the risk of cardiovascular disease independent of sex: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 10, 1114927.

Liguori, G., Feito, Y., Fountain, C., & Roy, B. (2011). American College of Sports Medicine (11th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

Lin, Y. K., Sung, F. C., Honda, Y., Chen, Y. J., & Wang, Y. C. (2020). Comparative assessments of mortality from and morbidity of circulatory diseases in association with extreme temperatures. Science of the total environment, 723, 138012.

Little MP, Azizova T, Richardson D, etal. Ionising radiation and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2023;380:e072924.

Liu, X., Wang, A., Liu, T., Li, Y., Chen, S., Wu, S., ... & Cao, C. (2023). Association of Traumatic Injury and Incident Myocardial Infarction and Stroke: A Prospective Population-Based Cohort Study. Reviews in Cardiovascular Medicine, 24(5), 136.

Loscalzo, J., Fauci, A. S., Kasper, D. L., Hauser, S. L., Longo, D. L. (Dan L., & Jameson, J. L. (Eds.). (2022). Harrison’s principles of internal medicine (21st edition.). McGraw Hill.

Lu, S. Q., Fielding, R., Hedley, A. J., Wong, L. C., Lai, H. K., Wong, C. M., ... & McGhee, S. M. (2011). Secondhand smoke (SHS) exposures: workplace exposures, related perceptions of SHS risk, and reactions to smoking in catering workers in smoking and nonsmoking premises. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 13(5), 344-352.

Lutwak, N., & Dill, C. (2013). Military sexual trauma increases risk of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression thereby amplifying the possibility of suicidal ideation and cardiovascular disease. Military Medicine, 178(4), 359-361.

Maculewicz, E., Pabin, A., Kowalczuk, K., Dziuda, Ł., & Białek, A. (2022). Endogenous risk factors of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) in military professionals with a special emphasis on military pilots. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(15), 4314.

Malakar, A. K., Choudhury, D., Halder, B., Paul, P., Uddin, A., & Chakraborty, S. (2019). A review on coronary artery disease, its risk factors, and therapeutics. Journal of cellular physiology, 234(10), 16812-16823.

Martinez, D., Klein, C., Rahmeier, L., Da Silva, R. P., Fiori, C. Z., Cassol, C. M., ... & Bos, A. J. G. (2012). Sleep apnea is a stronger predictor for coronary heart disease than traditional risk factors. Sleep and Breathing, 16, 695-701.

Masimova, A. E., & Mamedov, M. N. (2021). Risk factors for cardiovascular diseases and coronary artery disease among military population. Cardiovascular Therapy and Prevention, 20(1), 2702.

McMichael, A. J., Wilkinson, P., Kovats, R. S., Pattenden, S., Hajat, S., Armstrong, B., ... & Nikiforov, B. (2008). International study of temperature, heat and urban mortality: the ‘ISOTHURM’project. International journal of epidemiology, 37(5), 1121-1131.

Miller KA, Siscovick DS, Sheppard L, et al (2007). Long-term exposure to air pollution and incidence of cardiovascular events in women. N Engl J Med, 356(5): 447-58.

Milojevic A, Wilkinson P, Armstrong B, et al (2014). Short-term effects of air pollution on a range of cardiovascular events in England and Wales: casecrossover analysis of the MINAP database, hospital admissions and mortality. Heart, 100(4): 1093-8.

Mirzaeipour, F., Seyedmazhari, M., Pishgooie, A. H., & Hazaryan, M. (2019). Assessment of risk factors for coronary artery disease in military personnel: A study from Iran. Journal of family medicine and primary care, 8(4), 1347.

Mittleman MA, Maclure M, Tofler GH, et al (1993). Triggering of acute myocardial infarction by heavy physical exertion. Protection against triggering by regular exertion. Determinants of Myocardial Infarction Onset Study Investigators. N Engl J Med, 329(23): 1677-83.

Mohammadi, D., Zare Zadeh, M., & Zare Sakhvidi, M. J. (2021). Short-term exposure to extreme temperature and risk of hospital admission due to cardiovascular diseases. International Journal of Environmental Health Research, 31(3), 344-354.

Möller-Leimkühler, A. M. (2007). Gender differences in cardiovascular disease and comorbid depression. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 9(1), 71–83. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2007.9.1/ammoeller

Montone, R. A., Rinaldi, R., Bonanni, A., Severino, A., Pedicino, D., Crea, F., & Liuzzo, G. (2023). Impact of air pollution on Ischemic Heart Disease: evidence, mechanisms, clinical perspectives. Atherosclerosis, 366, 22-31.

Mosca L, Hammond G, Mochari-Greenberger H, Towfighi A, Albert MA. Fifteen-year trends in awareness of heart disease in women. Circulation. 2013;127:1254–1263.

Moslehi, S., & Dowlati, M. (2021). Effects of extreme ambient temperature on cardiovascular outcomes: A systematic review. Journal of Environmental Health and Sustainable Development.

Müllerova, H., Agusti, A., Erqou, S., & Mapel, D. W. (2013). Cardiovascular Comorbidity in COPD. Chest, 144(4), 1163–1178. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.12-2847

Münzel, T., Hahad, O., Sørensen, M., Lelieveld, J., Duerr, G. D., Nieuwenhuijsen, M., & Daiber, A. (2022). Environmental risk factors and cardiovascular diseases: a comprehensive expert review. Cardiovascular Research, 118(14), 2880-2902.

Murphy, C. N., Delles, C., Davies, E., & Connelly, P. J. (2023). Cardiovascular disease in transgender individuals. Atherosclerosis, 117282.

Naderi, S., & Merchant, A. T. (2020). The Association Between Periodontitis and Cardiovascular Disease: an Update. Current Atherosclerosis Reports, 22(10). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-020-00878-0

Newby DE, Mannucci PM, Tell GS, et al. Expert position paper on air pollution and cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J 2015; 36: 83–93b.

Nguyen, P. L., Alibhai, S. M., Basaria, S., D’Amico, A. V., Kantoff, P. W., Keating, N. L., ... & Smith, M. R. (2015). Adverse effects of androgen deprivation therapy and strategies to mitigate them. European urology, 67(5), 825-836.

Norris, C. M., Yip, C. Y., Nerenberg, K. A., Clavel, M. A., Pacheco, C., Foulds, H. J., ... & Mulvagh, S. L. (2020). State of the science in women's cardiovascular disease: a Canadian perspective on the influence of sex and gender. Journal of the American Heart Association, 9(4), e015634.

Nowrouzi-Kia, B., Li, A. K., Nguyen, C., & Casole, J. (2018). Heart disease and occupational risk factors in the Canadian population: an exploratory study using the Canadian community health survey. Safety and health at work, 9(2), 144-148.

Owen, A., Patel, J. M., Parekh, D., & Bangash, M. N. (2022). Mechanisms of post-critical illness cardiovascular disease. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 9, 854421.

Pagidipati,H., and Douglas, P. S. (2023). Management of coronary heart disease in women. UpToDate.

Panagiotakos DB, Chrysohoou C, Pitsavos C, et al (2002). The association between secondhand smoke and the risk of developing acute coronary syndromes, among non-smokers, under the presence of several cardiovascular risk factors: the CARDIO2000 case-control study. BMC Public Health, 2(9): 1-6.

Pandrc, M., Ratković, N., Perić, V., Stojanović, M., Kostovski, V., & Rančić, N. (2022). Prevalence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors for coronary artery disease and elevated fibrinogen among active military personnel in Republic of Serbia: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Medical Biochemistry, 41(2), 221.

Park, H., Cho, S. I., & Lee, C. (2019). Second hand smoke exposure in workplace by job status and occupations. Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 31, 1-9.

Parsons, I., White, S., Gill, R., Gray, H. H., & Rees, P. (2015). Coronary artery disease in the military patient. BMJ Military Health.

Parsons, I., White, S., Gill, R., Gray, H. H., & Rees, P. (2015). Coronary artery disease in the military patient. Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps, 161(3), 211–222. https://doi.org/10.1136/jramc-2015-000495

Peer, N., Abrahams, N., & Kengne, A. P. (2020). A systematic review of the associations of adult sexual abuse in women with cardiovascular diseases and selected risk factors. Global Heart, 15(1).

Pega, F., Al-Emam, R., Cao, B., Davis, C. W., Edwards, S. J., Gagliardi, D., ... & Momen, N. C. (2023). New global indicator for workers’ health: mortality rate from diseases attributable to selected occupational risk factors. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 101(6), 418.

Rahimi, A., & Afshari, Z. (2021). Periodontitis and cardiovascular disease: A literature review. ARYA atherosclerosis, 17(5), 1.

Rajendran, A., Minhas, A. S., Kazzi, B., Varma, B., Choi, E., Thakkar, A., & Michos, E. D. (2023). Sex-specific differences in cardiovascular risk factors and implications for cardiovascular disease prevention in women. Atherosclerosis, 384, 117269.

Reeder, G.S, Awtry E., and Mahler, S.A. (2024). Initial evaluation and management of suspected acute coronary syndrome (myocardial infarction, unstable angina) in the emergency room. UpToDate.

Reeder, G.S, and Kennedy, H. L. (2022). Diagnosis of myocardial infarction. UpToDate.

Rees VW, Connolly GN. Measuring air quality to protect children from secondhand smoke in cars. Am J Prev Med. 2006 Nov;31(5):363-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2006.07.021 PMID: 17046406.

Reynolds, H. R., Shaw, L. J., Min, J. K., Spertus, J. A., Chaitman, B. R., Berman, D. S., ... & ISCHEMIA Research Group. (2020). Association of sex with severity of coronary artery disease, ischemia, and symptom burden in patients with moderate or severe ischemia: secondary analysis of the ISCHEMIA randomized clinical trial. JAMA cardiology, 5(7), 773-786.

Rus, M. R. M., Johari, M. J. M., Hussin, F. R., Kassim, N. M., Zulkufli, M. R., Yunus, A. A. A., Zin, Z. F., Yusop, F., Yusof, S. M., Ani, C. E., Rani, N. H., Senin, N. A., Razak, M. A., Yatim, A. M., Hassan, N. H., Ringo, K., Rena, M., Khalid, K. A. A., Zawawi, M. F. A., … Shahril, N. S. (2021). Prevalence of atherosclerotic diseases and cardiovascular risk factors in military health care centres. International Journal of Cardiology, 345, 32–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2021.10.101

Rydz, E., Arrandale, V. H., & Peters, C. E. (2020). Population-level estimates of workplace exposure to secondhand smoke in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 111, 125-133.

Samet JM (2015). Secondhand smoke exposure: effects in adults.

Samet, J.M. (2022). Secondhand smoke exposure: Effects in adults. UpToDate.

Sancini, A., Caciari, T., Rosati, M. V., Samperi, I., Iannattone, G., Massimi, R., ... & Tomei, G. (2014). Can noise cause high blood pressure? Occupational risk in paper industry. Clin Ter, 165(4), e304-11.

Saw, J. (2013). Spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 29(9), 1027-1033.

Saw, J. (2023). Spontaneous coronary artery dissection. UpToDate.

Scott-Storey KA. Abuse as a gendered risk factor for cardiovascular disease: a conceptual model. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2013; 28: E1–8.

Shah AJ, Ghasemzadeh N, Zaragoza-Macias E, Patel R, Eapen DJ, Neeland IJ, Pimple PM, Zafari AM, Quyyumi AA, Vaccarino V. Sex and age differences in the association of depression with obstructive coronary artery disease and adverse cardiovascular events. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000741. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.113.000741

Skeer, M., Cheng, D. M., Rigotti, N. A., & Siegel, M. (2005). Secondhand smoke exposure in the workplace. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 28(4), 331-337.

Slater, M., Perruccio, A. V., & Badley, E. M. (2011). Musculoskeletal comorbidities in cardiovascular disease, diabetes and respiratory disease: The impact on activity limitations; a representative population-based study. BMC Public Health, 11(1), 77. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-77

Smaardijk, V. R., Lodder, P., Kop, W. J., van Gennep, B., Maas, A. H., & Mommersteeg, P. M. (2019). Sex‐and gender‐stratified risks of psychological factors for incident Ischemic Heart Disease: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of the American Heart Association, 8(9), e010859.

Smith GD (2003). Effect of passive smoking on health. BMJ, 326(7398): 1048-9.

Smith MR, Klotz L, van der Meulen E, et al (2011). Gonadotropin-releasing hormone blockers and cardiovascular disease risk: analyses of prospective clinical trials of degarelix. J Urol, 186(5): 1835-42.

Song, W. P., Bo, X. W., Dou, H. X., Fan, Q., & Wang, H. (2024). Association between periodontal disease and coronary heart disease: A bibliometric analysis. Heliyon, 10(7).

Steenland, K. (1996). Epidemiology of occupation and coronary heart disease: research agenda. American journal of industrial medicine, 30(4), 495-499.

Streed Jr, C. G., Harfouch, O., Marvel, F., Blumenthal, R. S., Martin, S. S., & Mukherjee, M. (2017). Cardiovascular disease among transgender adults receiving hormone therapy: a narrative review. Annals of internal medicine, 167(4), 256-267.

Sumner, J. A., Lynch, K. E., Viernes, B., Beckham, J. C., Coronado, G., Dennis, P. A., ... & Ebrahimi, R. (2021). Military sexual trauma and adverse mental and physical health and clinical comorbidity in women veterans. Women's health issues, 31(6), 586-595.

Svendsen KH, Kuller LH, Martin MJ, et al (1987). Effects of passive smoking in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Am J Epidemiol, 126(5): 783- 95.

Taylor, B. J. (2017). Beyond the War on Terrorism: Military Sexual Trauma and its Relationship to Cardiovascular Disease in Male Veterans (Doctoral dissertation, Northcentral University).

Troke, N., Logar-Henderson, C., DeBono, N., Dakouo, M., Hussain, S., MacLeod, J. S., & Demers, P. A. (2021). Incidence of acute myocardial infarction in the workforce: Findings from the Occupational Disease Surveillance System. American journal of industrial medicine, 64(5), 338–357. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.23241

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General—Executive Summary. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2006

University of Ottawa Heart Institute. (2024). A Guide to Your MINOCA. https://www.ottawaheart.ca/sites/default/files/documents/a-guide-to-your-minoca.pdf

Vaccarino, V., Sullivan, S., Hammadah, M., Wilmot, K., Al Mheid, I., Ramadan, R., ... & Raggi, P. (2018). Mental stress–induced-myocardial ischemia in young patients with recent myocardial infarction: sex differences and mechanisms. Circulation, 137(8), 794-805.

Vance MC, Wiitala WL, Sussman JB, Pfeiffer P, Hayward RA. Increased cardiovascular disease risk in veterans with mental illness. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12:e005563. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.005563

Veterans Affairs Canada (2024). Arterial Blood Supply. License purchased for use from Blood Supply To The Heart, Sites Of Heart Attack, Eps8 Royalty Free SVG, Cliparts, Vectors, and Stock Illustration. Image 9442885.

Vimalananda VG, Miller DR, Christiansen CL, Wang W, Tremblay P, Fincke BG. Cardiovascular disease risk factors among women veterans at VA medical facilities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:517–523.

Vogel, B., Acevedo, M., Appelman, Y., Merz, C. N. B., Chieffo, A., Figtree, G. A., ... & Mehran, R. (2021). The Lancet women and cardiovascular disease Commission: reducing the global burden by 2030. The Lancet, 397(10292), 2385-2438.

Wang, X., Jiang, Y., Bai, Y., Pan, C., Wang, R., He, M., & Zhu, J. (2020). Association between air temperature and the incidence of acute coronary heart disease in Northeast China. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 47-52.

Whitehead, A. M., Maher, N. H., Goldstein, K., Bean-Mayberry, B., Duvernoy, C., Davis, M., Safdar, B., Saechao, F., Lee, J., Frayne, S. M., & Haskell, S. G. (2019). Sex Differences in Veterans' Cardiovascular Health. Journal of women's health (2002), 28(10), 1418–1427. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2018.7228

Willich SN, Lewis M, Lowel H, et al (1993). Physical exertion as a trigger of acute myocardial infarction. Triggers and Mechanisms of Myocardial Infarction Study Group. N Engl J Med, 329(23): 1684-90.

Wilson, D. R., & Folkes, F. (2015). Cardiovascular disease in military populations: Introduction and overview. Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps, 161(3), 167–168. https://doi.org/10.1136/jramc-2015-000534

Wolf, K., Hoffmann, B., Andersen, Z. J., Atkinson, R. W., Bauwelinck, M., Bellander, T., ... & Ljungman, P. L. (2021). Long-term exposure to low-level ambient air pollution and incidence of stroke and coronary heart disease: a pooled analysis of six European cohorts within the ELAPSE project. The Lancet Planetary Health, 5(9), e620-e632.

World Employment and Social Outlook 2023: The value of essential work. Geneva: International Labour Office, 2023. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_871016.pdf

World Health Organization. (2019). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th Revision). https://icd.who.int/

World Health Organization. (2023). WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2023: protect people from tobacco smoke.

World Health Organization. (2023). A visualized overview of global and regional trends in the leading causes of death and disability 2000-2019. https://www.who.int/data/stories/leading-causes-of-death-and-disability-2000-2019-a-visual-summary

Wortley, P. M., Caraballo, R. S., Pederson, L. L., & Pechacek, T. F. (2002). Exposure to secondhand smoke in the workplace: serum cotinine by occupation. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 44(6), 503-509.

Wright EN, Hanlon A, Lozano A, Teitelman AM. The association between intimate partner violence and 30-year cardiovascular disease risk among young adult women. J Interpers Violence 2018; published online December 7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.01.016

Wright EN, Hanlon A, Lozano A, Teitelman AM. The impact of intimate partner violence, depressive symptoms, alcohol dependence, and perceived stress on 30-year cardiovascular disease risk among young adult women: a multiple mediation analysis. Prev Med 2019; 121: 47–54.

Zhang, D., Liu, Y., Cheng, C., Wang, Y., Xue, Y., Li, W., & Li, X. (2020). Dose-related effect of secondhand smoke on cardiovascular disease in nonsmokers: systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 228, 113546.